Fifty years ago, in the early 1970s, Joni Mitchell’s environmental protest song, Big Yellow Taxi, was a worldwide hit. Subsequently covered by many others from Bob Dylan to Counting Crows, perhaps its most poignant line was "Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone". In the case of biological extinctions, however, sometimes we don’t even know then.

In the 1930s the sea-grass (Zostera) beds that clothed intertidal mudflats on the Atlantic coasts of New York, New England and maritime Canada were devastated by disease. The sea grass disappeared from this vast area, surviving only in some brackish-water habitats. The animals that relied on sea grass — everything from crabs, sea urchins and marine snails to young fish — had to find other places to live and eat.

For one such snail, the sea-grass limpet Lottia alveus, however, there was nowhere to go. It lived only on the blades of sea grass growing on marine mudflats; it could not survive in brackish water, nor could it attach to nearby rocks or shells.

Lottia alveus became extinct. And no-one noticed for 60 years! The sea grass eventually came back, presumably re-populating the marine mudflats from the brackish refugia. But there were no sea-grass limpets. Everyone had assumed that the limpets living on clam shells and stones on the mudflats were the same species, but just looked a little different because they were attached to different surfaces. Surely, Lottia alveus was simply a form of the common tortoise limpet, Lottia testudinalis. But it wasn’t and the Atlantic sea-grass limpet is now gone forever.

In light of the sad story of the American limpet, my laboratory decided to investigate whether Notoacmea scapha was a sea-grass specialist, or simply an opportunistic generalist, able to live on all sorts of surfaces. We used genetics to see whether limpets from sea grass were the same as those attached to shells, stones and rocks.

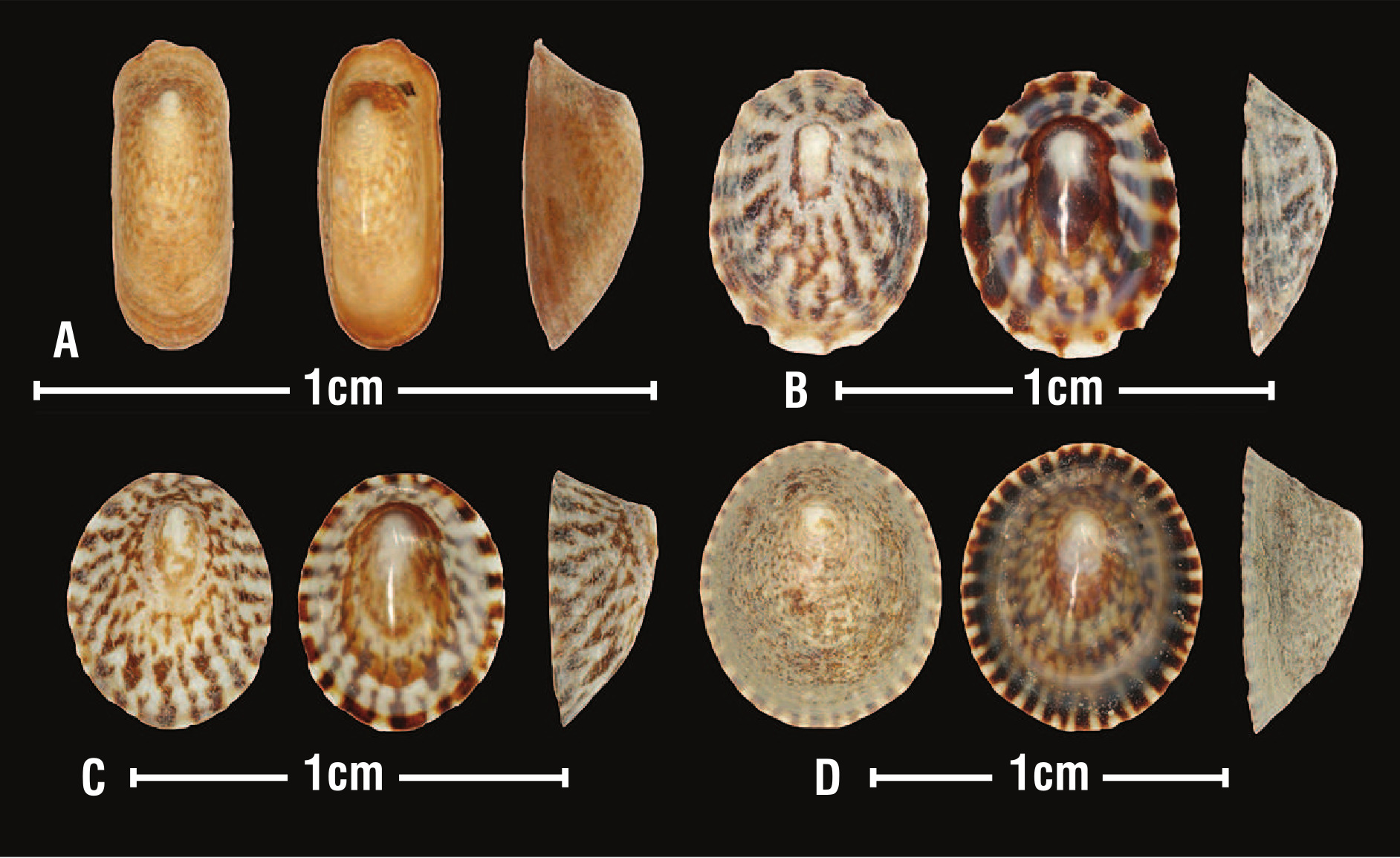

As seems often to be the case, the answer turned out to be quite complicated. Notoacmea scapha is not confined to sea grass: it is perfectly happy attached to cockles and small stones, although shells from sea grass look very different from those living on other substrates. This finding is especially good news because disease has, on occasion, hit our own Zostera beds, greatly reducing their coverage, albeit not as catastrophically as in North America. We can be reassured that any future dieback of Zostera is unlikely to lead to the extermination of our sea-grass limpet, which would survive on shells and stones.

But surprisingly, the limpets on the shells and stones were not all one species! Some of them were not Notoacmea scapha. In fact, there were two further species, with shells almost identical to those of Notoacmea scapha from stones and cockle shells. Bizarrely, these two species, both previously unrecognised by scientists, never live on sea grass.

One of these new species, which we christened Notoacmea rapida, behaves quite distinctively from all its relatives. It lives under rocks sitting on the mud or other rocks on sheltered shores. If you turn over one of these rocks, it immediately and quickly crawls away from the light, looking to hide back under its home rock. I recall finding the first one I collected from a discarded brick underneath the Auckland Harbour Bridge, not exactly a pristine site! I thought at the time, ‘this one is different; I haven’t seen that sort of speed from a snail before’. So far as I know, this is the first molluscan species to be discovered by noticing a difference in behaviour.

One of the tragedies of the current extinction crisis is that Joni Mitchell’s words are all too true. Even among well-known groups such as birds, we are still finding new species. Our lizards, insects, snails, plants, indeed almost any sort of living organism you care to name, are replete with unrecognised species. We are in a race to discover and save these species before they become extinct. Some are even on our very doorstep.

- Hamish G. Spencer is sesquicentennial distinguished professor in the department of zoology at the University of Otago.