It takes some searching, but the legacy of Rakiura-Stewart Island’s Norwegian whalers runs deeper than even their descendants realise, writes Bruce Munro.

The linkages, however, are fragile. Will this important piece of New Zealand’s maritime history be allowed to simply sink from view?

Hunting for foreign graves outside Oban township is the consolation prize, it would seem, for being too late to interview descendants of the Norwegian whalers who inadvertently changed the course of New Zealand history when they set up base on Rakiura-Stewart Island 100 years ago this week. Too late, by about a decade.

Fifteen minutes earlier, persistent knocking on the door of the hilltop home belonging to Owen Eriksson — son of one of the up to 40 Scandinavian whalers who caused consternation when they turned up here on April 4, 1924 — quickly revealed his health would not allow much conversation.

The only course of action; retreat to the bush-circled cemetery and rue the foresight of organisers of the 90th anniversary, in 2014, who knew many of the whalers’ direct descendants would not make the centenary.

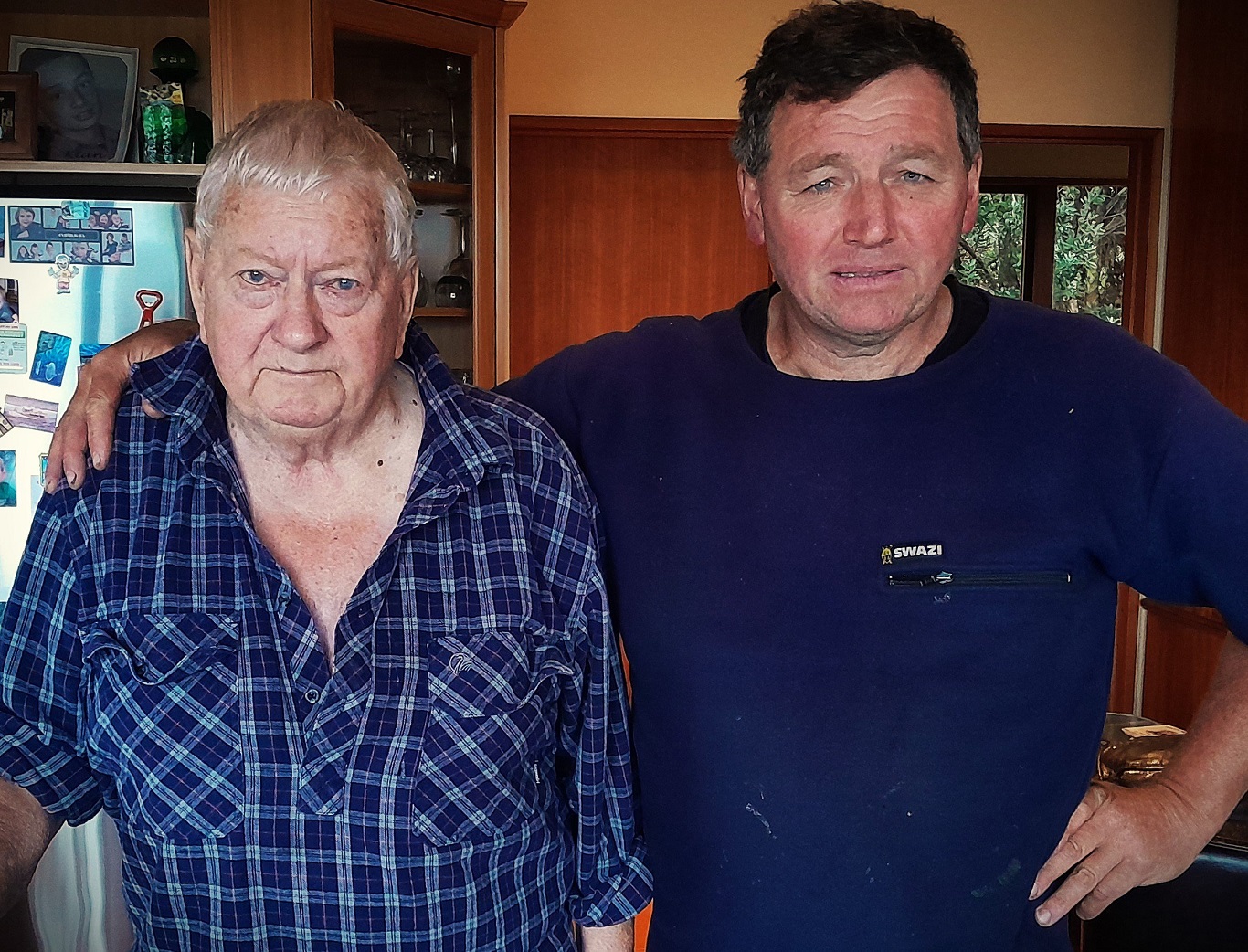

A cellphone jingle interrupts the funk. Owen’s nephew, Ray Jamieson, a Rakiura fisherman, has called the number on the business card left with his uncle. He gets the gist of the quest and agrees to chat.

Several minutes’ brisk walk later, the three of us are seated in Owen’s lounge and Ray is relaying what they know of their father and great uncle, whaler John Eriksson.

John, born near Stockholm, Sweden, in 1887, reached Rakiura in April, 1924, aboard the Sir James Clark Ross, the first mother ship of the Norway-based Rosshavet Whaling Company.

At first, the foreigners elicited fear in the local English-speaking settler community. But the employment they offered and their annual Norway Day celebrations — games with children on Oban’s beach followed by an evening dance at the hotel — won the locals over.

For a decade, the whalers spent each summer risking their lives in the frigid, tempestuous, whale-rich waters of the Antarctic’s Ross Sea. During that time, the whaling company chased, killed and rendered about 9000 Ross Sea leviathan, mostly blue whales.

The Norwegians also established the Kaipipi Shipyard, in Paterson Inlet. Each winter, while the season’s oil was taken to Europe, the whalers worked at the shipyard repairing their battered catcher boats.

A glut in the oil market and the Great Depression brought the Ross Sea whale industry to an end in 1933.

John Eriksson was aboard the Sir James Clark Ross when it made its final stop at Port Chalmers, bound for Norway, but spent too long at the Careys Bay hotel and missed the sailing. He never returned to Sweden.

John met Owen’s mother, Dorothy, a hotel maid, while milling timber at Port Pegasus, Rakiura.

They settled in Halfmoon Bay, where Owen and his sisters, Astrid and Inga, were raised.

One hundred years on, what is the legacy of Rakiura’s Norwegian whalers? Does their presence continue to be felt?

To what extent, for example, is Owen’s identity shaped by that heritage?

"What do you reckon Owen, do you feel Scandinavian?" Ray asks.

Owen shakes his head.

But in his study, another picture emerges. Prominent on one wall is a 70-year-old photograph of John Eriksson smiling at his best mate Morris Topi. Below it are two miniature Swedish flags.

It suggests the connection is more present, running deeper, than even the descendants themselves know.

Physical links are scattered throughout Oban, home to almost all 400 residents of the 1746sq km island.

There is a good whaling display at the Rakiura museum. But beyond that, you have to already know the links in order to spot them. A prefabricated house, brought out from Norway for favoured employee Harald Askerud, is one of four whaling base buildings still in use. This one has been relocated to Golden Bay Rd, where it proudly displays its Norse dragon-head finial.

Three of the 6.7m snekke (motor launches) are still afloat. The Else, which once took whaling company manager Nils Johansen’s family on picnics, was brought back to Stewart Island by bed-and-breakfast owner Raylene Waddell, who takes pride in having restored her.

"Whaling was an important but brutal part of the Island’s history," Raylene says.

"And what has survived? This little boat."

Matt Atkins, of Rakiura Charters, drops us on the beach to wander the remains of the whalers’ base.

A dozen large, four-bladed propellers, which gave the catcher boats great acceleration in their pursuit of whales, lie rusting on the beach, discarded after being too damaged by striking pack ice. Nearby are rusted mounds of whale catcher accumulator springs, which took the strain of the harpoon when the whale began to flee.

Jutting into the water are the remains of the slipway. Beyond it, half submerged, is the boiler that once powered the workshop. Further out, off the southwestern tip of the beach, lies the submerged hulk of the 1853, Moby Dick-era Pacific whaler Othello, beached here in 1927 to serve out her final years as a wharf for the Antarctic whalers.

At the top end of the slipway, hidden in the bush, is the cracked concrete floor of the workshop. And on the bush-covered rise to the northeast are the foundations of the manager’s house.

Jim, through his books and his advocacy, has done more than anyone to preserve the history of the whalers and bring the Kaipipi Shipyard to popular and official attention.

In time for the 90th anniversary, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, calling Kaipipi "a treasure", made the shipyard and its relics New Zealand’s first marine site to be granted specific legal protections.

Back then, the site was cleared of overgrowth and explanatory signage was added, making it a pleasure to explore. Visitors came regularly, either boating to Millers Beach wharf and walking the 20 minute track to the site, or taking tours, such as those offered by Matt. Over the years, he has brought whalers’ descendants from throughout New Zealand and overseas to visit.

Now the signage is weathered; the site is fast becoming a manuka nursery; the track, maintained by the goodwill of the Department of Conservation (Doc), is prone to subsidence; there is talk the Southland District Council-owned wharf at Millers Beach, if it needs to be upgraded, will instead be removed; and visitors are scarce.

"It has gone downhill, badly," Jim says.

"The value put on it seems to be based on the number of visitors it gets, not the value of it as an historic site for people to visit," Matt adds.

The key figure in the Rosshavet Whaling Company, of Sandefjord, Norway, was Carl Larsen. Already an experienced whaler, and with an eye to the untouched waters of the Ross Sea, Larsen and two friends set up the company, bought a ship, selected crew and applied to London for a whaling licence. Naming his ship the Sir James Clark Ross, after the English Antarctic explorer, might have been a helpful bit of flattery. The company was granted a 21 year licence.

What Carl’s plans also precipitated was Great Britain’s pre-emptive claim to the territory, in 1923, and that government’s decision to put New Zealand’s Governor-General in charge of the newly formed Ross Dependency.

This is a role the country still has today, governing, managing and protecting the 1.55 million sq km wedge that includes part of the Antarctic continent, the Ross Sea, the Ross Ice Shelf and Ross Island.

The scientific bases — Scott Base (New Zealand), McMurdo Station (United States), Marlo Zucchelli Station (Italy) and Kang Bogo Station (South Korea) — conducting world leading scientific research, are all within the Ross Dependency.

Investigating changes in the Ross Sea is one area of research with global ramifications, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (Niwa) principal marine physics scientist Craig Stevens says.

"Changes ... are having flow-on effects in the Southern Ocean. We will see these having impact in New Zealand and the world in the coming decades."

All this, thanks to a few dozen Norwegian whalers. But that knowledge can be lost sight of, forgotten. And the most obvious connections, genetic links to those men, get more tenuous with every year.

The phone call from Ray, nephew of Owen, son of John Eriksson, a Rosshavet whaler, albeit Swedish, was fortuitous.

Other efforts to find and talk to descendants, however distant, living on Rakiura, are fruitless.

Colin Hopkins, whose great aunts Rita and Violet Pollock married Norwegians, is off the island.

Lorraine Squires, a descendant of New Zealand’s 1920s, Bluff-based, Norwegian consul, Mathias Wiig, is unwell.

Jim Watt’s research reveals 13 of the whalers married New Zealanders. One couple returned to Norway, one stayed on Rakiura, but the rest, sooner or later, moved to the mainland — including Gus Gertson.

Gus was also Swedish. Carl Larsen, after approaching the Swedish government for funding for his whaling venture, promised in return to add some Swedes to his crew.

Gus arrived in Rakiura aboard the Sir James Clark Ross, spent the 1924 whaling season in Antarctic waters — he worked the steam winch on the mother ship because it was the warmest job — and then left for shipping and wharf jobs around the South Island. Gus and his Dunedin bride, Winifred, settled in Port Chalmers, where their only child, John, grew up.

John Gertson, 86, who still lives in Port Chalmers, says Gus was a great father, did not say much about his time whaling and, by the end of his life, could still read his monthly Swedish newspaper but could no longer hold a conversation in his mother tongue.

There was nothing particularly Scandinavian about his own upbringing, John says. But, somehow, despite the apparent paucity of input, a felt connection has thrived. In 1990, John and his wife, Rose, spent a nostalgic six weeks visiting Gus’ birthplace. And John, although not a man of the sea, has made 15 scale model ships, including the mother ship Sir James Clark Ross and two of the whale catcher boats.

All this has been researched by Jim Watt. The 85-year-old has meticulously gathered and preserved the information. He has done much to energise a generation of others, descendants and Islanders, to care about the lives and legacy of Rakiura’s Norwegian whalers.

But what will happen next? There is a real risk it will, with this generation, simply sink from view.

It needs a surer footing than waxing and waning enthusiasm.

That is why Jim is advocating for a Kaipipi Shipyard management plan.

"I would like to see a management plan developed, whereby this place is maintained at a presentable level, with good signage.

"I’m campaigning for the museum trust board to set up a committee that prepares a management plan."

"Doc is open to working with landowners and community on this site."

A Southland District Council spokesperson says some maintenance work on the Miller’s Beach wharf is planned.

The council is open to working with the community and Doc on the site, the spokesperson says.

Whether that all adds up to a management plan remains to be seen.

If the residents of Rakiura lose their awareness of, and sense of connection to, the Norwegian whalers, their sense of who they are will be that bit less rich. And if they lose that, so do we all.

At the moment, it is holding on in only a smattering of hearts.

Ray Jamieson sits with his uncle, Owen Eriksson, in a house that has stunning views across native bush filled with birdsong to a sandy estuary winding to the boundless ocean.

As a fisherman, Ray spends his days out there. But he has also read plenty on the Norwegian whalers.

"They were harsh conditions. They didn’t know comfort like we know it. They just got on and did it."

Riding the swells, he has seen humpback and southern Right whales passing Rakiura during their annual migrations. Not many, but more than there used to be, he says.

"I do get a bit of a thrill out of it, because there is that connection there."