JOCK GRAHAM THE POSTMAN

John Graham was born in 1831 in Strathblane, Stirlingshire, and arrived in Dunedin in February 1852 on Columbus with his sisters Catherine and Mary, Mary’s husband, James Hunter, and baby Catherine.

John, usually called Jock, found work building a bridge, subscribed to by residents, over the Water of Leith in 1853 and was soon writing to the Otago Witness to correct their report on the project. He mentioned that ‘‘half a dozen or more different parties gave several bottles of brandy, Hollands, and whisky, to the workmen, which I can assure you was gratefully received’’.

The coarse language in his next letter prevented its publication but he announced ‘‘a copy of my letter will be found at the Royal Hotel, when any who may choose to read it can do so’’.

His long career of constantly writing to the papers, and sometimes apologising to those he had criticised, was under way.

In 1856, he offered to deliver the mail and newspapers to Balclutha and return once a week to those who subscribed. In 1858, he won a tender from the Otago Provincial Council to carry out the same service for £150 (about $18,000) a year.

In the same year he married Margaret Marchbank, a daughter of James Marchbank, who had arrived in 1857 and farmed at West Taieri. A daughter, Catherine, was born to John and Margaret the following year.

The marriage later floundered, and Graham’s wife and child moved to live with her father. In 1869, Graham attempted, in vain, to retrieve his daughter but a melee ensued that led to a court case in which Graham ‘‘made a rambling statement as to his being the father of a girl who was living with her grandfather at Maungatua. That he went to fetch her away, and that instead of getting the child the defendant had hit him on the nose and made it bleed, and had also hit him a second time on the brow.’’

RED COAT

John Graham’s rise to legendary status came at the start of the gold rush when, with the support of postmaster Archibald Barr, he set up as the postman to the diggers, for whom piles of mail were arriving. Barr was overwhelmed and once spent three days and two nights in the office, taking his sleep in snatches upon the newspapers that were heaped upon the floor.

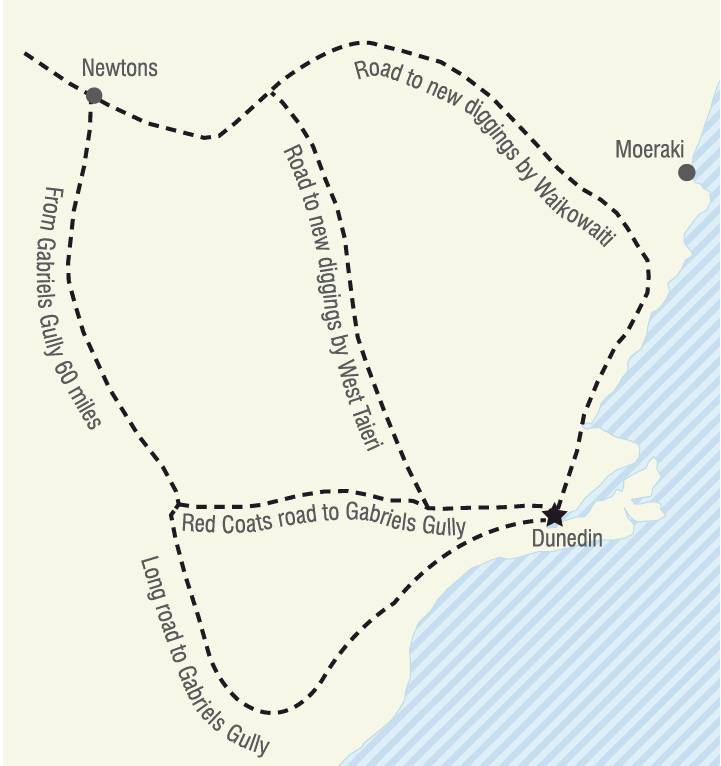

On July 27, 1861, Graham advertised in the Otago Witness: ‘‘Gold Diggings! Gold Diggings! The undersigned begs to intimate to the public generally that he intends, on and after this date, to run right through to the Gold Diggings by the West Taieri route, already established, arriving on the Diggings on the Mondays and leaving again on the Thursdays. Commissions of every description punctually attended to. John Graham. Postman.’’

Graham was soon being called ‘‘Red Coat’’ because of his red jacket. Since the 1790s, letter carriers in the UK had worn a scarlet tailcoat so the early Otago settlers naturally associated red with the garb of a letter carrier. As late as 1864, Graham was being sued by tailor William Sinclair, of High St (one-time foreman of Christie’s tailoring firm in Edinburgh), for £2 ($220 these days) outstanding from payment for ‘‘a redcoat’’.

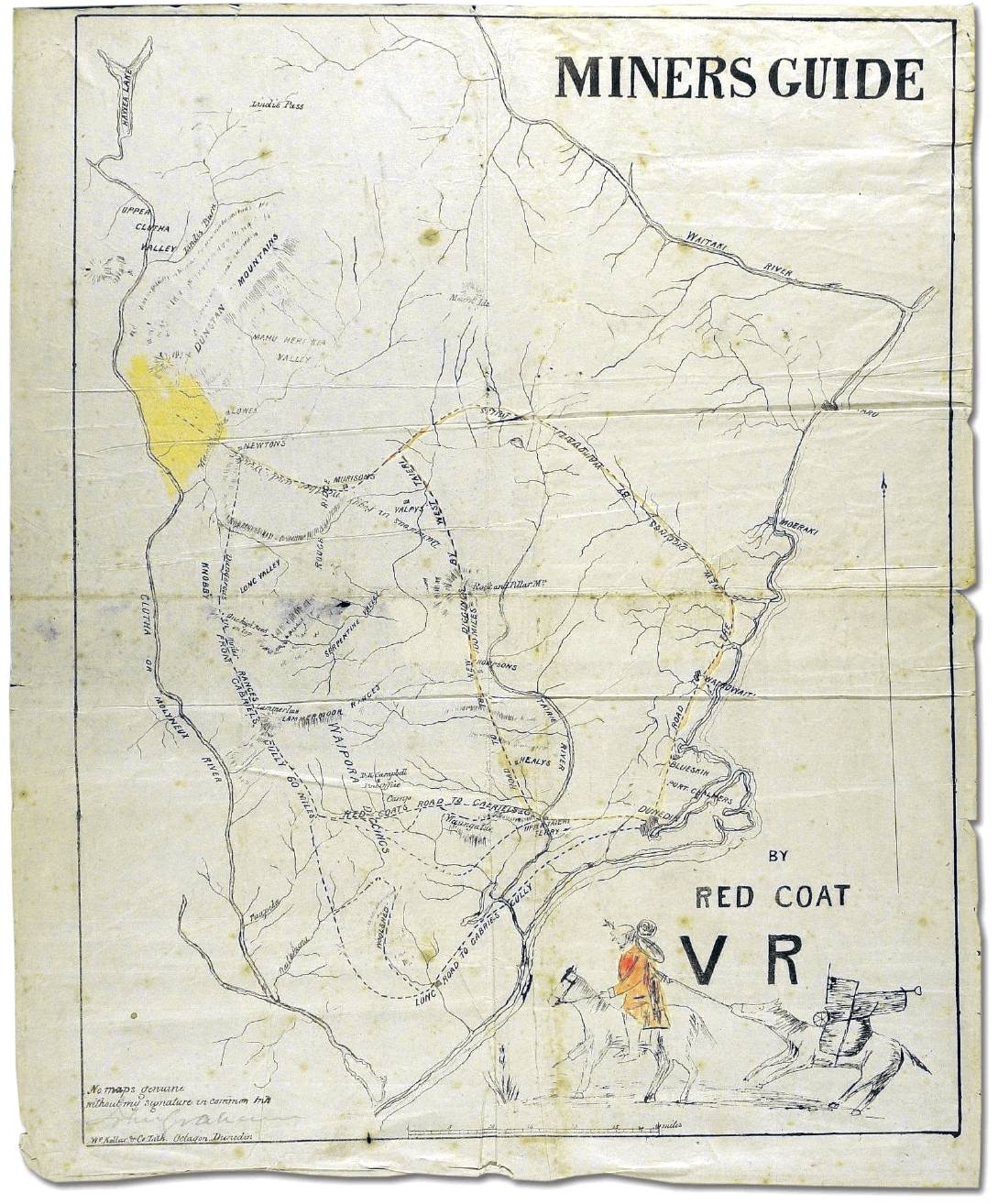

Graham became an expert on the routes to the goldfields at Tuapeka and then the Dunstan. Would-be miners needed to know how to get there but it was not until 1862 that official maps naming the goldfields appeared and arguments raged over the best routes.

With the discovery of gold at the Dunstan in 1862, the debate about which tracks to follow widened.

Although Cobb and Co began a coach service to the Tuapeka field in October 1861, most diggers would have walked to save money and thus Graham’s map, based on his own travel experience, was a popular item, although we do not know how many were sold.

Graham’s drawing style may have been primitive but lithographer John McKerrow produced an attractive item.

Graham signed each copy and, given that he has marked with yellow the Dunstan field, the map must have been drawn after July 1862 but before May 1863 as he omits the smaller Maniototo fields at Hogburn (Naseby), Hamiltons and Sowburn which began then. The gold finds at the Shotover and Arrowtown came in late 1862 but that area is not included in the map as Graham never offered a service to those more distant spots.

He marks the stations on the way as most runholders would sell food and give shelter as long as the diggers kept moving on. Valpy’s, (Patearoa Station) which suffered regular incursions by large groups of miners, is noted on the wrong side of the Taieri River but before long the alternative Dunstan Road provided a more direct route.

Graham’s warnings ‘‘dangerous in fog’’ and ‘‘dangerous in winter’’ were based on bitter experience, while a note about ‘‘one high rock on top’’ would reassure the diggers tramping beneath the Nobbies.

When not on the road, Graham, a tall man with a booming voice, gave advice from a spot in Stafford St explaining to the diggers who swarmed up from the new jetty how they should set a course to get to the site of Hartley and Reilly’s claim on the Clutha and advertising his services.

The Otago Daily Times in September 1862 reported: ‘‘A well-known, and somewhat eccentric, Dunedinite, rejoicing in the soubriquet of ‘Red Coat’ went through the town on Saturday on horseback, announcing at the corners of streets to the inhabitants, called together by sound of trumpet, that he was about to proceed to the Hartley Diggings, and that merchants, grass widows, forsaken sweethearts and others, wishing to forward letters would find, upon payment of half-a-crown (about $12), that Red Coat would prove a fast and faithful courier.

‘‘As Red Coat is well known to be a messenger whose probity may be relied on, there is no doubt but many will find such a medium of the utmost service, in the absence of any direct postal communication.’’

AFTER THE RED COAT DAYS

Within a year or so, Cobb and Co coaches were carrying the mail and Graham ended his arduous journeys through rain, snow and flooded rivers, which had left him with rheumatism and other complaints that eventually had him reliant on crutches to get about. He took up selling cheap carcasses of mutton in Rattray St and then at a stall in the Octagon.

He gained more notoriety in 1865 when he heard that the West Coast goldfields were overrun by rats and rushed to Hokitika with a cargo of about 50 cats, hoping to get £3 (about $350 today) each for them, but his project was scuttled by a Christchurch entrepreneur with the same idea who arrived on the Coast just before him.

Within a year or so, Cobb and Co coaches were carrying the mail and Graham ended his arduous journeys through rain, snow and flooded rivers, which had left him with rheumatism and other complaints that eventually had him reliant on crutches to get about. He took up selling cheap carcasses of mutton in Rattray St and then at a stall in the Octagon.

He gained more notoriety in 1865 when he heard that the West Coast goldfields were overrun by rats and rushed to Hokitika with a cargo of about 50 cats, hoping to get £3 (about $350 today) each for them, but his project was scuttled by a Christchurch entrepreneur with the same idea who arrived on the Coast just before him.

He later ran the book stall at Dunedin Railway Station and was constantly in the news as a regular dabbler in politics, usually on the side of the working man.

He stood for election many times, including tilts at a seat in the House of Representatives and an attempt to become provincial superintendent. He attracted few votes, his lowest return being just one vote but, with fellow eccentric J.G.S. Grant, he enlivened the political meetings of the 1870s and published a newspaper and tracts to spread his gospel.

He spent his last days in the Benevolent Institution where he died at the age of 87 in 1904. A copy of his map and the bugle he used to attract an audience and announce his welcome arrival on the goldfields are held at Toitu Otago Settlers Museum. Should anyone attempt a ‘‘History of Otago Characters’’, Jock ‘‘Red Coat’’ Graham deserves his own chapter.