Meeting Shayne Carter in person, up close, for the first time, thoughts fly immediately to the early pages of his just-released autobiography.

With clean, eloquent prose, the man who has forcibly carved his name and those of his bands, Straitjacket Fits and Dimmer, in the history of New Zealand rock music writes honest, affecting sentences about the bruising realities of growing up in 1970s Dunedin.

"I'm being pushed around a playground in Brockville by a series of headbutts to my face. We're in a flat concrete area beside the community hall where children go to ride skateboards, and I'm being attacked by a boy called Smith who has a hole in his jersey and a sort of eczema on his face. He just rammed his skateboard into my ankle and started butting me with his hard, malnourished forehead. I don't fight back. I hardly ever do. I accept this assault instead, and wait for its shower to pass.''

There is something that is equal parts childlike softness and hard-bitten steel about Carter as he stands here in the foyer of the Otago Daily Times Dunedin office reluctantly, resolutely refusing requests to revisit old haunts for publicity photographs.

With lean body, angular jaw and dyed-auburn hair, he is a timeless Peter Pan. But a Peter Pan forged by hurt and heartbreak, dressed all in black, in his sixth decade and still punk to the core.

So, outside it is, to take photos - not in Caldwell St, Brockville, where he was raised by a mum and two dads; not on the Kaikorai Valley College assembly hall stage where his pubescent punk band first performed; nor at Coronation Hall, Maori Hill, where Bored Games played to large teenage crowds and got bashed by carboys - but in the nearby alleyway along one edge of the ODT building and on the steps of the High Court across the road.

Ten minutes later, having chosen the stairs over a ride in the newspaper's claustrophobic and erratic lift, Carter is seated at the large, oval, wooden table in the editor's temporarily vacant office.

In front of him, is an advance copy of Dead People I Have Known.

The 54-year-old jokes that he decided to write his autobiography because he was getting old and wanted to do it while he still had his faculties.

The real reason is more prosaic. He has always wanted to write something longer than a song, he likes non-fiction and he had a story so he thought he might as well tell it.

Two years ago, after returning to Dunedin when his mother died, Carter was lent a crib at Aramoana to hole-up in and write.

Getting going was not easy.

"I hadn't written any extended prose in yonks ... It was like trying to squeeze out a refrigerator,'' he admits with offbeat frankness.

During a period of about five months, he laboured over the first quarter of the book. In it, he accounted for his life from birth in Christchurch, on July 7, 1964, to young parents on the run from their families; through his upbringing in the violence and addiction-ridden existence of working class, suburban Dunedin; to the early gigs as an untrained musician, whose bands Bored Games and The DoubleHappys were unwitting contributors to the globally influential Dunedin Sound.

At the end of that period of writing, however, unhappy with his efforts, Carter took an extended break.

"I couldn't recognise my voice. It was this person trying to self-consciously write `a book'.

"But I do enough creative stuff to realise failure is a big part of it. By failing you work out what is actually right.''

He rewrote the first chunk. And then kept going, until he was finished. In five-and-a-half weeks, he wrote 150,000 words.

He is pleased with the result - Dead People I Have Known, by Shayne Carter. Four hundred and seven pages, published by Victoria University Press. A raw, insightful, sad and sometimes hilarious, first person account by one of the leading contributors to an important chapter in this country's discography.

"Yeah, totally ... I figure that is my voice. My voice is quite terse, with some liberal swearing thrown in,'' he says with a throaty chuckle.

"I like minimalism in most of the stuff I do, whether it is music or writing ... Quite often an innocuous phrase carries a lot more weight if you look at it again.''

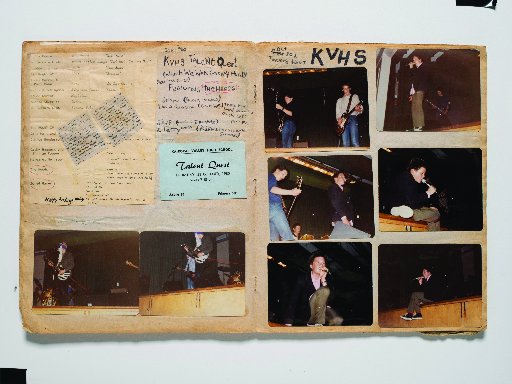

IT IS there, for example, when he writes about Bored Games' debut at the then-Kaikorai Valley High School's talent show in a hall crammed with pupils and their families.

"We plan to stick it to them from the top,'' Carter writes.

"Fraser smacks down on the opening chord of `I Wanna Be Your Dog' before the curtain even moves, and by the time it's shovelled over he's already down to E. The rest of the band trundles in, the trailer behind his truck.

"Ted, my little sister's teddy bear, is tucked beneath my arm. I'd planned to use Ted as an ironic prop, but from the opening note his days are numbered. Within the first minute he's been torn limb from limb and scattered across the stage. My 7-year-old sister looks on from her seat, horrified ...

"It's hardly what the crowd expects. It gets worse in the so-called chorus, where one line is repeated until it becomes clear that what you think is being said is actually being said.

"Now I want to be your dog! Now I want to be your dog!''

Carter's autobiography is honest. Sometimes, painfully so.

How The DoubleHappys became Straightjacket Fits after the death of band member and friend Wayne Elsey. Struggles to craft songs while surviving on the poverty line. Partnerships, and run-ins, with other bands.

Being picked up by Flying Nun and dropped by Sony. Repeated bouts of losing and winning the battle with drugs. Touring the United States and Europe. Years of self-imposed isolation while still producing albums as Dimmer. The death of parents and his return to Dunedin.

Writing about one of his stints in Auckland, Carter says,"At first I was broke and I often had nowhere to live. I owed the record companies money from records that would never recoup, so I'd be sent statements showing astronomical amounts that bore no relevance to my life ...

"Another time, before the first Dimmer record came out, I slept on cushions at a football friend's place. He was a driver for a brothel where his girlfriend worked. Each day he'd take half-hour showers, as if he was trying to scrub the thought of that away.

"After my father died, I was still homeless and destitute, this time freshly kicked out by my girlfriend. I was grieving. And I was also concerned about a hole in my ear[drum] . . .

"I got depressed and watched pornographic gifs on slow dial-up internet and thought I'd probably die. That's when I started drinking again.''

It is all laid quite bare.

But Carter says that is just what he does.

"I feel the same way about my music. It is good not to be scared of that. But it's also easy to be brave and cavalier when you are sitting on your own in a room.

"I thought, in admitting to my shortcomings, I don't care what other people think. If anyone's going to judge me on that, well, let's go have a look through their drawers.''

Others' drawers do get pulled open at times.

Disingenuous record company personnel, the novelist who ended up with his girlfriend, various other Kiwi and international musicians, the sleazy owner of an all-night dairy...

Carter is certain some people will be disgruntled by what they read.

"I can only write from my experience. My biggest conundrum was how to treat other people fairly. I didn't want to use it as an instrument of vengeance.

"But having said that, a couple of people who I find annoying, purely through the averages of chemical interactions, I stuck it to them. Good on me,'' he laughs.

While the book is replete with Kiwi and international icons of the music industry, and beyond - "Sometimes, when Dimmer played, we had Jacinda [Ardern], David Parker, Barbara and Grant Robertson dancing up the front'' - it also includes smaller players; everyday citizens who Carter identifies as his people.

"I wanted to give a voice to that side of life in New Zealand.

"I wanted to write something quite visceral that also represented those lives.

"There's a lot of battles, noble and otherwise, going on out there that you never hear about.''

Some of these characters add needed levity.

There is the story of a fellow primary school pupil who offered to demonstrate a new-found skill. The incident is too bawdy to be repeated here.

"That's one of my favourite scenes in the book,'' Carter says guffawing.

"And it's exactly what happened. We got bored and said we'll see you back up at the shops.''

Many of these "everyman'' characters have been given pseudonyms to protect their privacy, Carter says. Although, he admits, he forgot to mention that in the book's acknowledgments.

The title, Dead People I Have Known, existed before the first word was written.

Early on in the writing process, Carter thought he might focus each chapter on a different deceased person, telling, through his interactions with them, his own story.

In the end, it was not how he wrote it. But there are still a lot of them. Dead people. Friends, foes, family. Diseases, accidents, suicides.

Looming large is the death of his classmate, band member and friend, Wayne Elsey. Elsey was killed when he and Carter, travelling south from Auckland by train at night after a successful DoubleHappys tour in 1985, climbed down on to the outside steps of the moving carriage.

"We were both laughing as the wind shook us around, while the countryside stood further out, black, lightened by the fog,'' Carter writes.

"Maybe Wayne called out something, but it ended mid-sentence.

"There was an explosion and a thump, and the violence of the train wheels on a different-sounding track. I was hanging outside the train, almost parallel to the side of the carriage, yet somehow I still held the rail.''

Elsey had been hit by a bridge abutment they had not seen in the dark, killing him instantly. His body had slammed into Carter, cracking two of his ribs, but also knocking him out of harm's way.

The traumatic accident was the end of The DoubleHappys and the genesis of one of Carter's best songs, Randolph's Going Home.

The sergeants says he's just back there so come with me

And somewhere Randolph's gaily singing I'm set free

Set free

Lonely, lonely like a mother's cry

This anger seems the only thing that never dies

Never dies

And Venus lies alone

Fanfares fade into drones

Line up to cry cause Randolph's going home ...

Death inevitably shapes those who come into contact with it.

Yes, it is a painful, but also profound, experience, Carter says.

"The flipside of death is life. If anything, the positive thing that death teaches you is gratitude for life, plus gratitude for people.

"Mate, I feel gratitude every day. I've been living out at Aramoana. I'd do that drive in and look at the different light on those peninsula hills every day. I'd think, well that's pretty good, I'm glad I'm around to see that.''

Carter has spent his entire adult life moving on. From one tour, one band, one relationship, one home and one country to the next. All of it is digested and memorialised in his music.

He had seen the music industry from most angles by the time he formed Dimmer and was writing what he considers his best record I Believe You Are A Star.

Released in May, 18 years ago, the album and its title track were a robust critique of the music industry's treatment of its talent.

On the album cover, a lone trotter named Dimmer runs on an empty track under glaring floodlights.

In the video for the song, Carter, dressed as a jockey, sings in the ear of the horse, which is ultimately pipped at the post to the disgust of a suited punter.

I believe you are a star

Because you beam above my head

And they say you'll travel far ...

But you're exactly like the rest

You're exactly like the rest.

"It's a harsh business,'' he says.

"I didn't want my book to be a complaint about how hard it was, and poor me, and all that kind of stuff. But at the same time, the music industry, any entertainment industry, is harsh.

"You have a use-by date and then you're just tossed on to the pile.

"I think that's why many performers of different ilks get screwed up later on ... 'cause one minute they've got 60,000 people screaming for them and the next they're forgotten.''

A fortnight ago, Carter was discussing this exact issue with fellow artists after the sold-out Tally Ho 3 concert in the Dunedin Town Hall.

"When you're a performer, you're constantly being judged by people. You ask for it, because you put yourself out there, to a certain degree.

"You have to have a certain sensitivity to be an artist. But at the same time, you have to be tough. You have to be able to put that shell on.''

Tally Ho 3 raises an interesting point. One theme in Carter's book, a ringing theme in his life, is the punk ethos, "f*** you''.

Any good art has to have something to react against, he believes.

"Dunedin, back in the day, gave me a lot to react against. It was white, it was conservative, it was quite oppressive ... it was cold. There was a lot to kick back against.''

But Tally Ho - Dunedin Sound songs set to orchestral music and performed with the Dunedin Symphony Orchestra - is a long way from sticking it to The Man.

The irony of performing in front of a town hall filled with "respectable'' people is not lost on him.

"That was the same music that got us beaten into the gutter as kids in Dunedin, and now we're getting standing ovations.

"But that's also just time and the respectability of getting older.''

Has he lost some of that punk verve?

"I called my last album Offsider. By that I meant, a bit ... out of step.

"In the mainstream there's the status quo. A lot of people just drift along with the status quo.

"The people who make positive change are the people who question that shit.

"So, when you ask, do I still think f*** you? Yes, I do.''

Maybe not in such a rude way now, he says with a sudden laugh.

"But in my brain that's what I'm saying. While outside I'm saying `Oh, well, I don't know whether I necessarily agree with that'.''

ACCOLADES have come Carter's way.

He was named Most Outstanding Musician for I Believe You Are a Star. For his efforts on that album, the New Zealand Listener called him "New Zealand's greatest rock star''. He was inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame. In 2005, at the bNet New Zealand Music Awards he was given a Lifetime Achievement Award. It was presented by then-Prime Minister Helen Clark.

Dead People opens with that scene.

"I'm in the town hall with my head in a pot full of serotonin. About me is the full scent of perfume, freshly pressed jackets, fear, alcohol. I have taken a pill, a very strong pill, and the first effect of it has just dropped. My bandmates all wear baffled looks that probably mirror my own.

"Half an hour ago we opened the show with two of our favourite tunes, and when our last chord died, it lifted skywards and stayed in the rafters like an old-school victory banner ...

"It is now apparent that her speech concerns me. There is no joy in this realisation, just an immense dread, brought on by the potent E.

"`And the bNet Lifetime Achievement Award goes to Shayne Carter,' the Prime Minister says, confirming my fears.

"The audience claps and starts to stand, and I stand too, like I've been sent to the gallows.

"I set out on a lonely walk.''

The awards and opportunities have continued.

More recently, when the Apra Silver Scroll Awards were held in Dunedin, in 2017, Carter was asked to be music director.

Last year, he was selected for a three-month artist residency, in Thailand. He returned just last month. That was an invigorating experience.

"Before that, I didn't even know if I wanted to make another record,'' he says.

"But I worked with some Thai musicians and that was really inspiring.

"To me it was like the blues. It was like the music of an oppressed, disadvantaged population. It's really cool music. They use their traditional instruments. Great sound. It's music of funk and integrity.

"I might go back to Thailand and do a bit more work with those people. I'd really like to go back and do some recording.''

But success does not guarantee contentment.

"I guess I'm that personality type that will always have an itch.''

Carter's book reveals that one lifelong itch has been the search for a deep, intimate, stable relationship.

There have been numerous relationships. For Carter it has meant countless heartbreaks.

"I learned early on that empty bonking wasn't worth it,'' he writes.

"Because for me, f***ing someone is never casual. There's too much heat, and residual feeling, for that.''

Dialling a Prayer, one of his favourite Straitjacket Fits songs, is a case in point.

People point to She Speeds as a great example of what the band was about. But Carter picks Dialling as one of the best songs he has written, because "that song is a tank. It works whether you play it with a band or on an out-of-tune acoustic.

"And it cooks the whole way through.''

It is about unrequited love.

Well you wind me up

just to let me go

To see if what's promised is really so ...

And it feels like I'm dialling a prayer

It's like no one's there.

That insatiable itch also finds expression in a fondness for romantic movies, which Carter admits to in the book.

"I have a secret romcom fetish, even though most of them are crap. Serendipity, When Harry Met Sally and About Time are all good ones. It's something about the wish fulfilment and the happy ending.''

He writes that life on that front, so far, has not been as fulfilling.

"Mostly I've been in a string of relationships that last two to four years, and then I leave, or I make them leave, because no matter where I am, it's never enough.''

Is he looking for something bigger than what a relationship can provide?

"Issues like that, man, I feel like I've given up so much in the book that I don't want to psycho-analyse myself in the press.''

For a sensitive artist in the public eye, foregoing deep connection might appear the necessary price of self-preservation.

"My solace is that ... you can read that book, but you don't know me. We all operate from a core that is ours and ours alone.

"I can give you all the facts, but I've still got my core that can't be touched.

"That's my sanctuary. I think you need that to stay sane.''

At the festival

• Shayne Carter will appear as part of the Dunedin Writers & Readers Festival (May 9-12) at Dead People I Have Known: Shayne Carter on Thursday, May 9, 6pm at Hanover Hall. Carter, in conversation with Steve Braunias, will discuss his new autobiography, his music career and what it was like to grow up in Dunedin.

• Dead People I Have Known, by Shayne Carter, Victoria University Press, is published May 9, RRP $40.