One such innovation is the vault light, or pavement light, which is essentially a panel of glass blocks in a concrete or cast-iron frame set into the pavement. They allow natural light to enter a basement storeroom or workroom beneath street level.

Vault lights are more innovative than first appearances might suggest. Instead of cube-shaped blocks, the glass is shaped into prisms with a flat surface at pavement level and an angled lower section that is triangular when viewed side-on. This design allows light to bend (or refract) and fan out into the room below, making the below-ground space much brighter than could be achieved with plain glass blocks.

Vault lights were adapted during the late 1800s from conically shaped boat deck lights, which were first used in the 1840s to light internal spaces, especially where an open flame would have been hazardous such as colliers (bulk cargo ships designed to carry coal).

By the late nineteenth century, vault lights were common in many countries, but by the 1930s their use had declined as electric lighting became more affordable.

A number of companies were involved in vault light development and manufacture, including St Pancras Ironworks (founded 1860s) and Haywards Brothers. But it was the American prism glass company, Luxfer, that played a key role in introducing the natural interior lighting revolution from the 1890s. Vault lights were relatively expensive to install but promised substantial savings over time, as well as improved working conditions. They were also a healthy alternative, with no heat, noxious vapours, dirt, disease, maintenance costs or fire risk concerns to worry about. Luxfer offered three quality grades of glass and nine different degrees of refraction to suit various lighting requirements.

Vault lights were first patented by Thaddeus Hyatt in 1845. Hyatt came up with the idea of using small, round glass pieces instead of the earlier style single panes, which were unsafe. James Pennycuick patented the rectangular-style vault light in 1882, and this design formed the basis for Luxfer’s subsequent success. Many Luxfer vault lights can still be seen in Dunedin.

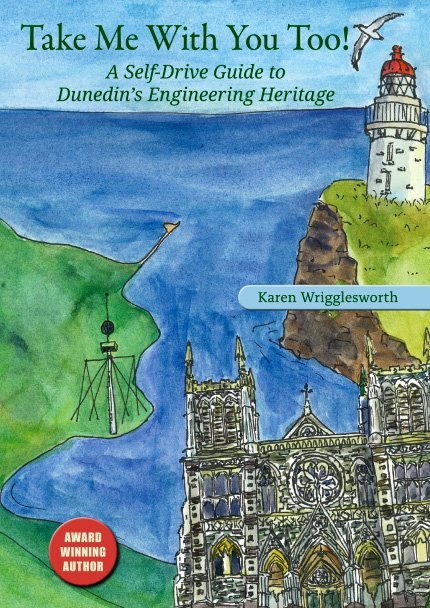

The book

Extracted from Take Me With You Too!: A Self-Drive Guide to Dunedin’s Engineering Heritage by Karen Wrigglesworth, published by Cliff Creatives, RRP $48