I remember, as a child, sitting in the kitchen talking to my mother about what, in those days, we called the Māori Wars. At that time, it was not uncommon to be teased by my Pākehā classmates, who claimed they were in charge because they had beaten us in the Mowri wars.

My mother is Pākehā and her grandparents had moved to New Zealand after the Highland clearances. My father is Māori from the Ngāti Maniapoto and Waikato iwi (tribes). I was probably worried about how unfair the wars were. I distinctly remember her mentioning that the "Hauhaus" were "terrible people", and I recall thinking, "How does she know they were terrible?", "How does she know about the Māori Wars?", and "I can’t believe we were in the wrong".

I found out how she knew a few years later when she showed us an old school journal, where the story Children of the Forest, a memoir of the childhood of A.H. Messenger, had been serialised. It told of Messenger’s life as the son of an officer who was guarding a frontier post at Pukearuhe, north of New Plymouth, to stop Māori in the King Country from reaching through to Taranaki in the early 1880s. There was one particular description of a fearsome Māori leader, Te Wētere, who had led the attack at Pukearuhe that killed five men, a woman and three children in 1869. Messenger described how they had "gazed fearfully at this tall sinister figure" and wrote, "I remember that all that night in my dreams I was being chased by tattooed Maori warriors".

So this was where my mother had got her vision of the "Hauhaus". It had obviously made a lasting impression on her.

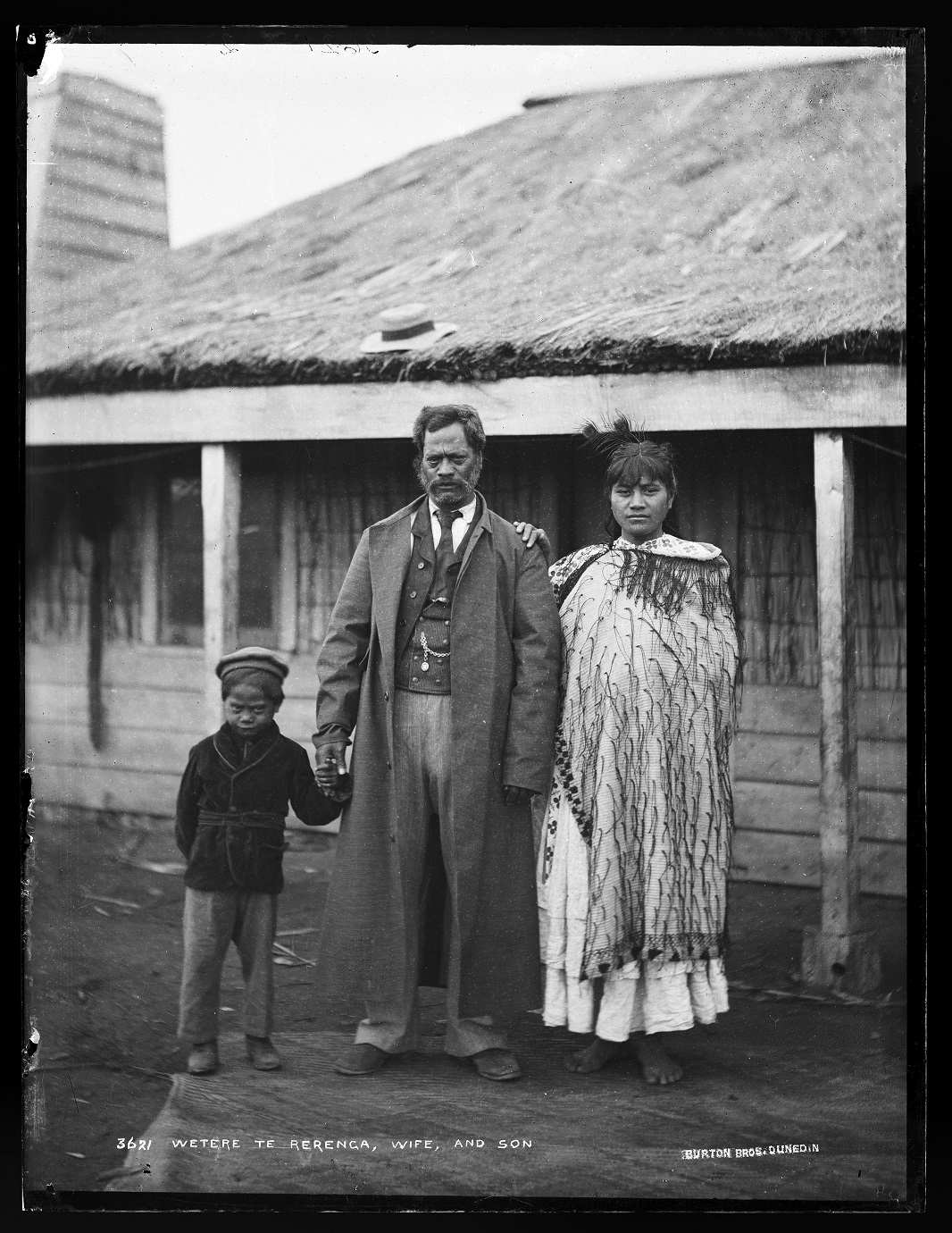

In the mid-1980s I was visiting home from Auckland and my mother pulled out a Dunedin Weekender article on the 19th-century photographers, the Burton Brothers. One photo stood out to her and she had saved it because the man in it looked exactly like my father in his mid-40s. The resemblance was so uncanny she had ordered extra copies of it. I looked at the caption and saw the name "Wetere Te Rerenga Great Mokau chief ". It was the very same Te Wētere who had formed her image of the Hauhau some 30 years before. I looked at my mother and said, "That is Dad’s great-great-grandfather". It was so ironic: the man she married was both the descendant and spitting image of the bogeyman that had such an impact on her as a child.

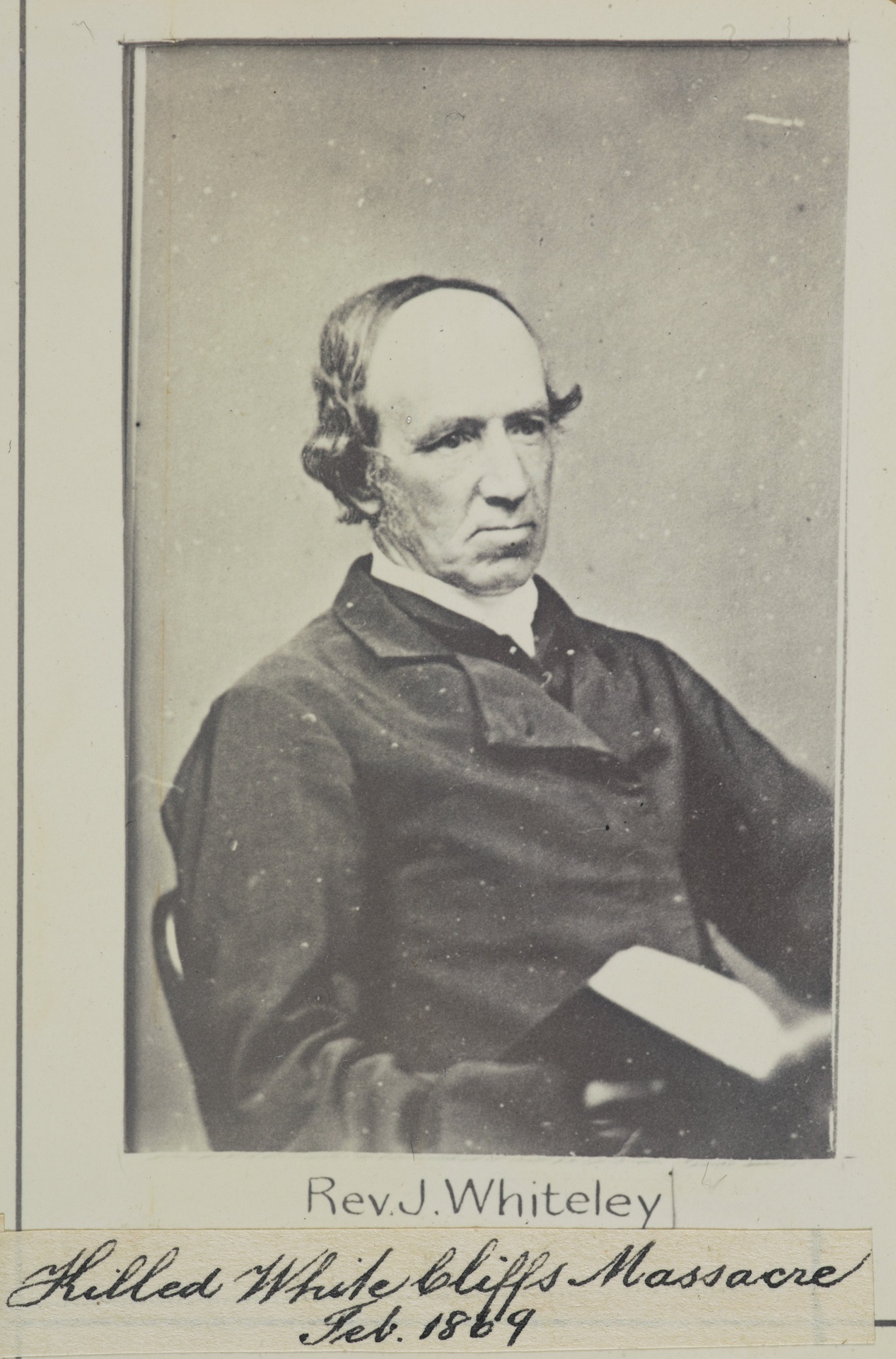

For over 150 years my great-great-great-grandfather Wētere Te Rerenga has been referred to as the murderer responsible for the death of the Methodist missionary the Rev. John Whiteley, a claim that is disputed by the family to this day. Whiteley was among those killed in 1869 at Pukearuhe, a military redoubt at Parininihi, a natural boundary between Taranaki and the Tainui tribes of Ngāti Maniapoto and Waikato. The attack on Pukearuhe redoubt was a defining moment of the war against the Waikato–Tainui tribes because these were the last shots fired in anger in that conflict; the gunship rounds launched at Mōkau pā a few weeks later were the last shots of the Taranaki war.

The first part of the attack on the redoubt is reasonably clear. Wētere Te Rerenga led a party of around 15 men to attack the Pukearuhe redoubt by deception. They pretended they had pigs to sell, and while the four soldiers stationed at the fort were separated from one another, the attackers killed them with tomahawks. They also killed the wife of one of the soldiers and her three children, aged five, three and three months. It was as grisly a scene as you can imagine. Even the dog was killed.

The men gathered some of the bodies together and buried them in a shallow grave. They then searched for arms and ammunition and anything else of value that they could carry. But as the group prepared to leave, a lone rider was seen approaching. It was John Whiteley, on his regular visit to parishioners. Whiteley had previously been a missionary to the Ngāti Maniapoto and Waikato tribes for over 30 years. Now, while he still had Māori parishioners, he spent most of his time with the new settlers who had moved to Taranaki in search of land. Whiteley had become discouraged by the behaviour of Māori. In his view, God had commanded mankind to go forth and replenish the earth, including turning wilderness into productive land. He believed that Māori were disobeying God by not selling land they weren’t using to settlers who would fulfil God’s commands. So strongly did he feel about this that he had written to the Times in London, calling for resources to defeat Māori and put an end to their love of land, which he referred to as "idolatry". His views were well publicised, and he was apparently also known for reporting to the government on the movement of rebel Māori forces.

Now, as he approached the redoubt, Whiteley’s horse was shot from under him and he was hit by five bullets. The physician who later examined the body reported that each one would have been fatal.

The attack on the military settlers was sudden, although there had apparently been warnings that were not heeded. The murder of a woman and her three young children by axe was brutal. But the land wars had moved on from the so-called chivalrous engagements of the early Waikato War (1863–64). Colonial troops had killed Māori women and children at Rangiaowhia in February 1864; and nearby, at the other end of Ngāti Maniapoto country at the Battle of Ōrākau, captured women had been bayoneted. However, the murder of John Whiteley seemed to cause the most consternation and have the longest-lasting effect. Here was the so-called "friend of the Māori", supposedly murdered by the man he had baptised and given the new "Christian" name Hone Wētere, John Wesley, the name of the founder of Methodism. From that time until this, the Methodist Church has dominated the narrative. Whiteley wasn’t just murdered, he was martyred: a true martyr killed because of his faith. The Methodist version of this story is as self-serving as the family narrative I will discuss later.

The authorised version was written by William Morley, a young minister who had moved to Raglan to work originally with Waikato Māori and was to marry Hannah Buttle, the daughter of an early Methodist missionary to Ngāti Maniapoto. Hannah would have known Whiteley well, as his old mission station in Kāwhia was also in Ngāti Maniapoto territory. Morley blames Wētere and repeats several times Whiteley’s status as a martyr. The need for a martyred John Whiteley, rather than a murdered one, was important. Tertullian, writing in the second century about how martyrdom makes Christianity strong, wrote, "The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church". Martyrdom is an important part of the history of the Christian church and is believed to lead to a purification of the church that will bring revival. Therefore, all the facts of Whiteley’s death had to feed into this narrative: Whiteley’s conversation with Wētere stressed his position as a shepherd looking after his flock; and he had died at the hands of his one-time acolyte who had turned from the faith, as he knelt in prayer beside his horse.

Yet there were other narratives as well. One of the stories that emerged was that a Pākehā member of the group had instigated the murder, had cried out "Dead cocks don’t crow" and fired first. This death at the hands of a Pākehā was reported early on by the Daily Southern Cross newspaper but dismissed as a lie. As one reporter said: "There is a horrible report now current among the natives, and by them generally believed, which I trust, for the honour of our race, will prove utterly false. It is to the effect that the murderers at Pukearuhe, or White Cliffs, were accompanied by two white men, and that the Rev. Mr. Whiteley met his death at the hands of one of them ... I give you this as I have heard it — a Māori report. I can hardly credit myself that any such bloodthirsty renegades, capable of such atrocities on their own countrymen, women, and children, can be in existence."

In other words, it could not have been true as no white man would have done this sort of thing to another white man.

Wētere claimed David Cockburn killed Whiteley. In this he was supported by Rewi Maniapoto, the most important chief at the other end of Maniapoto territory (although he was not at the scene at the time), who also claimed that Cockburn fired the first shot. Benjamin Ashwell, an Anglican missionary in Waikato, reported to his superiors that two Pākehā had killed Whiteley; and Cort Schnackenberg, one of the missionaries who had served with Whiteley in Maniapoto territory, claimed from the outset that it was said a Pākehā was responsible for the death.

The man in question was referred to as Wētere’s white slave or "taurekareka", though the more accurate term would be "mōkai", which sometimes means slave but is closer in meaning to "pet". Cockburn had deserted from the British army in 1865 from the very area that had been attacked. He had gone to live with Ngāti Maniapoto, where he had five wives. If Cockburn was indeed there, it makes sense that he would not have wanted any witnesses to his involvement. While many Māori would not have been afraid of British justice, as a soldier Cockburn would have had intimate knowledge of British military discipline and what he could expect if it became known that he had committed treason by taking up arms against his country. There would be little reason for the Māori involved to hide their identities. They would not have needed to worry about Whiteley warning other settlers, as the mere fact that they torched the buildings as they left would have drawn locals from far and wide. Also, Whiteley was killed by several bullets, the discharge of which could have raised the alarm. Upon their escape, they might have tied up Whiteley easily enough. It is more likely that the Pākehā man present, a deserter, was in most need of no witnesses.

In the eyes of Pākehā, the most damning account was by a "half-caste", Henry Phillips, who signed a confession in September 1882 to a local shopkeeper and a farmer. Phillips claimed that he and some companions had come up from the south. Having been ferried across the Mimi River by Captain Messenger, they had met Wētere north of Pukearuhe, and Wētere had forced him to accompany his party as a translator. Phillips said he witnessed the killings but had not participated in them; Wētere, he claimed, had decided that whoever the rider was, he should be killed.

It is doubtful that Wētere would have wanted a translator, as a number of contemporaries noted that he was fluent in both written and spoken English. And there were other discrepancies in Phillips’ story. Captain Messenger recalled talking to a man that day who had demanded to be ferried across the Mimi River with his friends. Messenger was concerned about the type of men they were and was suspicious of their motives. Wētere also claimed that Phillips was one of the men who shot Whiteley. In fact, Phillips is probably the person referred to as the second Pākehā, as it was not unusual for Māori to refer to "half-castes" as Pākehā, just as Pākehā call "half-castes" Māori.

The timing of Phillips’ confession is interesting. A few weeks earlier, a telegram had fallen into the hands of the newspapers that claimed Wētere had made a full confession to the killing of Whiteley. It was a fake produced by Whiteley’s grandson, John Whiteley King. King was angry that Wētere had been travelling freely to Wellington to meet with Cabinet minister John Bryce and had not been arrested by the government. It may be that Phillips was rushing to get a competing story out. Within a week of Phillips’ confession, Wētere, along with Te Kooti and others, had received a full pardon from the government for their wartime activities. It would have been interesting to see Phillips’ confession if he knew that he, too, was to be pardoned. As for Wētere, even though he now had a full pardon, he maintained until his death that he was not responsible for Whiteley’s death.

THE FAMILY STORY

Wētere Te Rerenga led the attack but always maintained that he was not responsible for the death of John Whiteley. However, family history is always contextual and can change in response to the dominant thinking of the time. One family narrative comes from Sister Heeni Wharemaru, one of Wētere’s descendants, born in 1912. Heeni wanted to do church work, but her parents were reluctant. However, after some discussion, they released her to the work of the Methodist Church. In an interview, Sister Heeni said, "So without really understanding why at the time, I was given over to the Methodist Church partly as an offer to make reparations" for the death of Whiteley. Sister Heeni became a well-known deaconess of the Methodist Church, where her service was seen as part of the family’s response to Whiteley’s death; while Sister Heeni knew of the association, she rarely mentioned it.

I did not hear of it until 1983 at my grandmother’s funeral. An uncle was teasing my grandmother’s cousins about how our ancestor was a murderer and had killed a missionary. One of my relations snapped back that it was all wrong and Wētere was a great man. There was still some residual shame associated with this and the conversation stopped abruptly. I was interested to note the change in family demeanour at a family reunion in the late 1990s, where there was even some pride in the death of Whiteley. The revision of New Zealand history had taken place and the missionaries were no longer seen as the heroic workers of the past but often as land grabbers who used their influence to rob the natives. They were seen as the vanguard of the British colonising mission, sent by a greedy empire to prepare the way for a treaty to allow settlement to extend British power.

The death of a missionary who, at first glance, appeared to fit this profile was not only seen as justified, it had also become almost a badge of honour as an example of resistance to colonisation. As I was always interested in whakapapa (genealogy), I asked an uncle, Rongo Wetere, whether Wētere had indeed killed Whiteley. His reply was, "Yeah, he did it". I was dubious about this response, as it conflicted with other stories. Twenty years later, in 2018, I approached him again and questioned him about what he had said. He modified his explanation: although Wētere hadn’t pulled the trigger, he was responsible because he was in charge. This less enthusiastic response maintained Wētere’s innocence of the actual murder but retained a little of the reflected glory of someone who had been part of the resistance.

Wētere had not always been antagonistic towards Pākehā; both before and after the attack, he had proven protective of Europeans. He had protected the missionary Cort Schnackenberg in 1865 when tribal members wanted to harm him, as well as the military officer Charles Hutchinson, also in 1865. The following year he had protected three white men who had entered the King Country from Taranaki, and had personally escorted one for three days to Te Awamutu to enable him to go to hospital. He rescued a couple of surveyors from the followers of Te Kooti in 1883, and in 1886 he received a medal from the Royal Humane Society of Australasia for rescuing two surveyors whose boat had foundered on the Mōkau bar. Wētere Te Rerenga was pardoned for his activities in the land wars in 1883 and worked to encourage settlement in his tribal area on his terms. He ran unsuccessfully for Parliament in 1884, and when he died in 1889, he was receiving a £100 pension from the government, the same as that given to Whiteley’s widow.

John Whiteley was killed because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time: it didn’t matter who he was. It was claimed he was killed so he would not raise the alarm, but he could have been tied up or locked in the blockhouse; the gunfire and smoke from the burning buildings would have been enough to alert people nearby.

The idea that a white man had killed Whiteley was dismissed early on, as the reality was the church needed a martyr. The land wars had seen a great falling away from the church. The early missionary successes had been overtaken by ambivalence among many Māori, who had started turning their backs on the church. The land wars were seen by many in the church as a punishment from God for their turning away from Him. The martyrdom of a longstanding significant missionary only served to prove the evil that lurked within the Māori race, and showed that the lack of success was due to Māori ourselves rather than any betrayal by the settlers.

The Europeans’ rejection of the idea that a white person could do something as terrible as kill another white person was farcical. Methodist historian Rev. Morley wrote, "Whiteley was told to go back, but an evil voice and surely not that of a Pākehā, cried out in the darkness ‘Kāhore e tangi ngā tikaokao mate’, ‘Dead roosters do not crow’."

This story was not something that was talked about in the family and was addressed only when I raised it. It had become almost obliterated from memory, a legacy of guilt. In the end, I don’t think this silence was about the death of Whiteley, although his death was the last action of the Waikato wars. To my mind, it was about the death of a woman and three children, one of them a three-month-old baby. That doesn’t rest easy with anyone.

Anaru Eketone is an associate professor in social work at the University of Otago, and Otago Daily Times columnist. While his research interests are in Māori economic and social development, he also has an interest in the impact of religious movements in his tribal area.

The book

The book

Aftermaths: Colonialism, Violence and Memory in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific, edited by Angela Wanhalla, Lyndall Ryan and Camille Nurka, explores the intergenerational effects of colonial violence in Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia and the Pacific. Published by Otago University Press, to be launched April 27 at University Book Shop, from 5.30pm.