Literally in the dust too, in the case of Catlins archaeologist, teacher-tutor and legend Les Lockerbie.

Not bound by the strictures and arcane rules and customs of academia as to how science should be done and who should be doing it, the non-academic is free to more easily bring decades of practical knowledge, experience and common sense, to their subject.

A new book by Mosgiel author and former Owaka schoolteacher Malcolm Deverson delves into the life of the man who made groundbreaking discoveries from early Māori sites around the Catlins, was an early adopter of radiocarbon dating, and who proved southern giant moa still lived in the area when the early Polynesian voyagers arrived.

Remembering Les Lockerbie: Pioneer archaeologist and educator, published by The Catlins Historical Society, was launched last Saturday at the Owaka Memorial Community Centre. Soon after, the Owaka Museum opened its Lockerbie Room, attended by about 200 people.

Lockerbie, by all accounts a hard-working, modest and dedicated family man, took on the establishment, represented by Canterbury Museum ethnologist and director Dr Roger Duff no less, proving once and for all that stratigraphy is a valid method for providing a timeline of early settlement.

At the 1957 New Zealand Archaeological Association conference in Dunedin, Lockerbie dropped what became known as his "bombshell" to explode previous theories of Early Māori life in Otago.

His persistent toil, his humble leadership and teamwork on expeditions to sites around the Catlins, had paid off.

By PAUL GORMAN

"I hadn’t heard of him either. Sometimes you don’t know enough about your local history."

The idea for the book came from a meeting of the society.

"We were going to open the Lockerbie Room. That had been the focus for several years, to be able to display all these artefacts and records and papers in a room dedicated to Les’s work.

"We thought it would be a good idea to do a wee something to go with it, a wee pamphlet or something. That grew into a bigger booklet and eventually, once I saw all the stuff, I realised it needed a bit more treatment.

"I have written other stuff, nothing published, but I enjoy writing and thought I’ll have a go at putting together a story that his daughter, Frances White, and other people might think was OK."

Deverson wrote the book in about six months and spent almost as long editing it.

"We wanted all the information to match. It’s no good saying something in the book and something different on the storyboards in the room.

"I saw the creative task as putting that text together with the items that were relevant and the memories that I asked people to write."

Lockerbie attended teachers’ college in Dunedin and Christchurch, and then taught at Clinton School and Purekireki School during the 1930s. His enthusiasm for Māori culture continued to grow.

After a period of World War 2 service, he and wife Ina moved to Dunedin where he taught at Macandrew Intermediate School and studied anthropology at the University of Otago, coming first in a class of 26 and receiving a rare first-class pass.

Late in 1947, he began as Otago Museum’s education officer, a role he thrived in, running classes and providing materials for students and teachers, and developing all kinds of teaching materials, including the well-known glass-fronted loan cases holding actual and replica artefacts.

By the time he retired in 1976, Lockerbie had amassed a significant reputation as an innovative educator. During his work career, he had carried on with his archaeological endeavours in almost every spare moment, leading museum expeditions around the South. In 1956, he was awarded the Percy Smith Medal for published work in anthropology on early Māori sites.

The bald facts of someone’s employment rarely do justice to their most significant achievements. As Deverson told those at the book launch, Lockerbie was ahead of his time in several ways, including "in acknowledging and even highlighting the importance of Māori in our history through his archaeology, and also in teaching aspects of Māori culture in his primary school career as early as the 1930s".

"There’s no claim that he was any sort of radical proponent, and it is very unlikely that he used reo Māori at all, except in association with the customary Māori songs and games that he encouraged in his classrooms. I’m suggesting they were small but important steps."

Lockerbie’s accomplishments in the field around parts of the South were also "important steps", but in the context of New Zealand archaeology they certainly weren’t small.

It’s not an easy question for Deverson to answer.

"It’s hard to identify the most important thing he did because of the range of things he did. He was able to work on several fronts at the same time."

Deverson points to the introduction to his book, in which he says Lockerbie wanted the thousands of artefacts he found to speak for early Māori and late Māori, their lifestyles and cultures.

Strata diagrams

He helped define a new approach to archaeological field work, "his careful noting of the layers [strata] that artefacts were found in was later followed by all New Zealand’s professional archaeologists".

At the book launch, Deverson said Lockerbie "realised early on that it would be sensible to note at what depth in an excavation particular items were found".

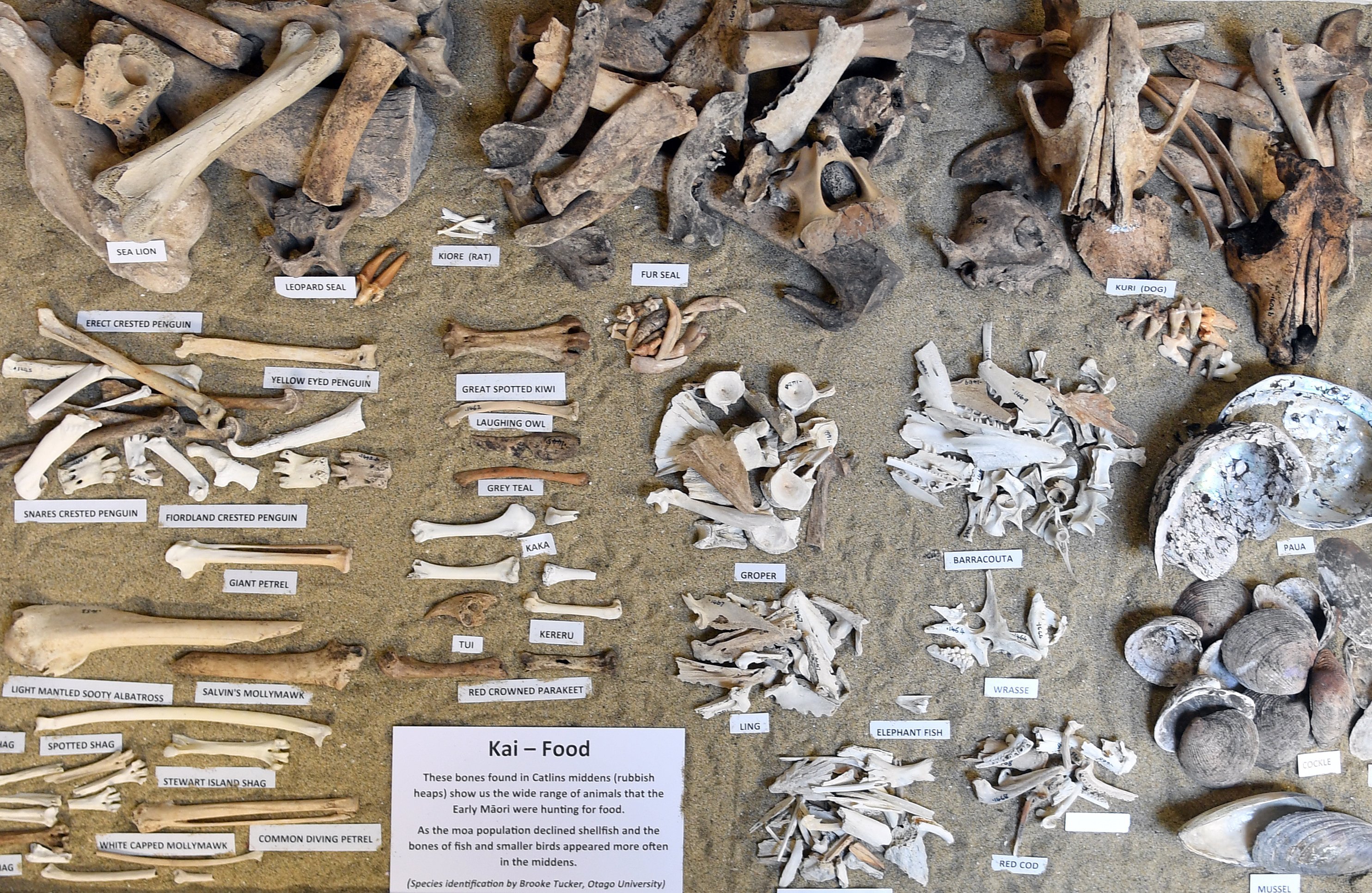

"If an oven with fish, seal or penguin bones was found at the same depth as a strata containing moa bones or moa bone fish hooks, then it could be fairly claimed that moa were indeed at that site at the same time as early Māori. Site maps and strata diagrams became the norm for professional archaeologists after Les’s example."

In the introduction, Deverson says Lockerbie excavated hundreds of fish hooks, fish-hook points and adzes of traditional Polynesian design from around the South, and these were dated from between the 13th to the 17th century.

"With this wealth of carefully collected information, he was able to establish a general progression from a largely moa-hunting culture to one more dependent on long-held fishing knowledge. Les certainly confirmed that the early Māori period lasted considerably longer in the South Island than the North Island, and probably longer south of the Waitaki River than anywhere further north."

Moa

Lockerbie also made amazing discoveries about the plight of moa and the cause of their extinction.

"Les excavated the bones of all the moa species that lived on the southeast coast of the South Island, as well as those of the upland moa which lived in the Southern Alps. He also discovered bones of the giant moa, which had not previously been found in conjunction with early Māori artefacts in the South.

"The number of moa bones, alongside moa-bone fish-hook points, awls, necklace reels and pendants, showed that humans were indeed the overwhelming cause of the extinction of the moa."

It was the excavations at the southern end of Tautuku Bay which established that southern giant moa were still here when the first voyagers arrived.

This was a major discovery, as the book explains: On the high dune on the peninsula the team found the articulated leg bones of a South Island giant moa (now known scientifically as Dinornis robustus).

This new discovery was in firmly packed brown sand immediately below where Russell Glendinning had earlier excavated into clean white sand and found smaller bone fragments and other artefacts.

The giant moa bones were in a layer that was also found to have other moa bones and artefacts.

It was a significant find, as the South Island giant moa were not thought to have been present in New Zealand when the earliest Māori settled this land from around 1250AD.

These giant moa bones (tarsus, tibia and femur) were dated at the time at 1670AD. A recent reassessment of C-14 dating in New Zealand has shown this date to be too recent.

Radiocarbon dating

Deverson explains that Lockerbie was also in the vanguard of adopting radiocarbon dating to narrow the range of ages of old organic materials such as bone, shells and wood. He worked closely with nuclear chemist T. Athol Rafter, who began using carbon-14 dating techniques in New Zealand in the 1950s.

Samples from the Tahakopa River mouth and the now gone Pounawea sites, which were home to Māori villages for perhaps as many as 400 years until sometime between 1650 and 1726, were probably the first in Aotearoa to be carbon-dated, back in the early 1950s, he says.

It’s no exaggeration to say his "bombshell" in 1957 ranks up there with some of New Zealand’s most seminal historical findings.

In an article in the Journal of the Polynesian Society in 1953, Lockerbie discussed the excavation of the "moa-hunter" camp at the mouth of the Tahakopa River. According to the book, in this "it appears that Les is challenging the archaeological ‘establishment’ in the person of Dr Roger Duff", who "persistently denied that stratigraphy gave convincing evidence" for the timing of settlements.

The theory, promoted by Duff, was that moa had been dying out naturally and that only smaller moa species were still alive when the first Polynesians arrived.

By the time of the May 1957 New Zealand Archaeological Association conference in Dunedin, Lockerbie was confident enough to debunk established thinking about early settlement through his paper ‘‘he culture sequence in the Murihiku area of the South Island’’.

"In essence, four points about the archaeological history of the Dominion were settled by Mr Lockerbie," the paper said:

1. That all the seven genera of moa were surviving in parts of Otago when the first men — Polynesian moa-hunters — first arrived in the district, some time in or before the 12th century.

2. That the barbed fish hook, found in many excavation sites, is an ancient feature of Polynesian culture dating back before the development of the classic Māori.

3. That there were definite stratification levels in sites excavated around Otago, sometimes to a depth of 9ft (2.7m).

4. That some moa-hunter remains underlie a level occupied by classic or recent Māori.

The article said Duff "stated that he was glad to be the first to congratulate Mr Lockerbie on his ‘magnificent paper’ in which he had clearly demonstrated his points’’.

Duff "conceded" that the giant moa and all the other genera survived in the Murihiku area when it was first occupied.

Deverson says Lockerbie’s finding was hugely significant.

"He just found things that didn’t fit with convention.

‘‘He was a nice guy and a good family man as well, who got on with his passion and let the world get on with itself."

— Remembering Les Lockerbie: Pioneer archaeologist and educator is available from The Catlins Historical Society at the Ōwaka Museum.