It’s funny. Kinda.

Kirt Gandhi has been an UberEats delivery person for just a few months. Prior to that he was a Dunedin restaurant manager and owner for almost 20 years.

Delivering meals for the global online food ordering and delivery platform suits him well. He works when he wants, only make the deliveries he chooses and logs off when he pleases.

His only concern is that through the huge success of UberEats he might be complicit in breeding a lazy generation.

"It's good for my earnings, but at the same time ..." Gandhi says, his voice trailing off.

A lot of his deliveries are in the student quarter. When he accepts a job, the app on his phone does not give the specific delivery address until he has picked up the order.

"The address comes up ... and Google maps is showing me that I’ve already arrived," he recalls, still incredulous.

So, he leaves his car parked outside the food business where he picked up the order and walks 100m to make the delivery.

"You go and deliver and it’s not to a very old person, it’s young chaps.

"So, that is not good. I can see that this is making them more lazy because everything now is getting home-delivered."

It is a sign of the times. One of the more innocuous signs, perhaps, of an enormous societal shift that Covid-19 has put on steroids.

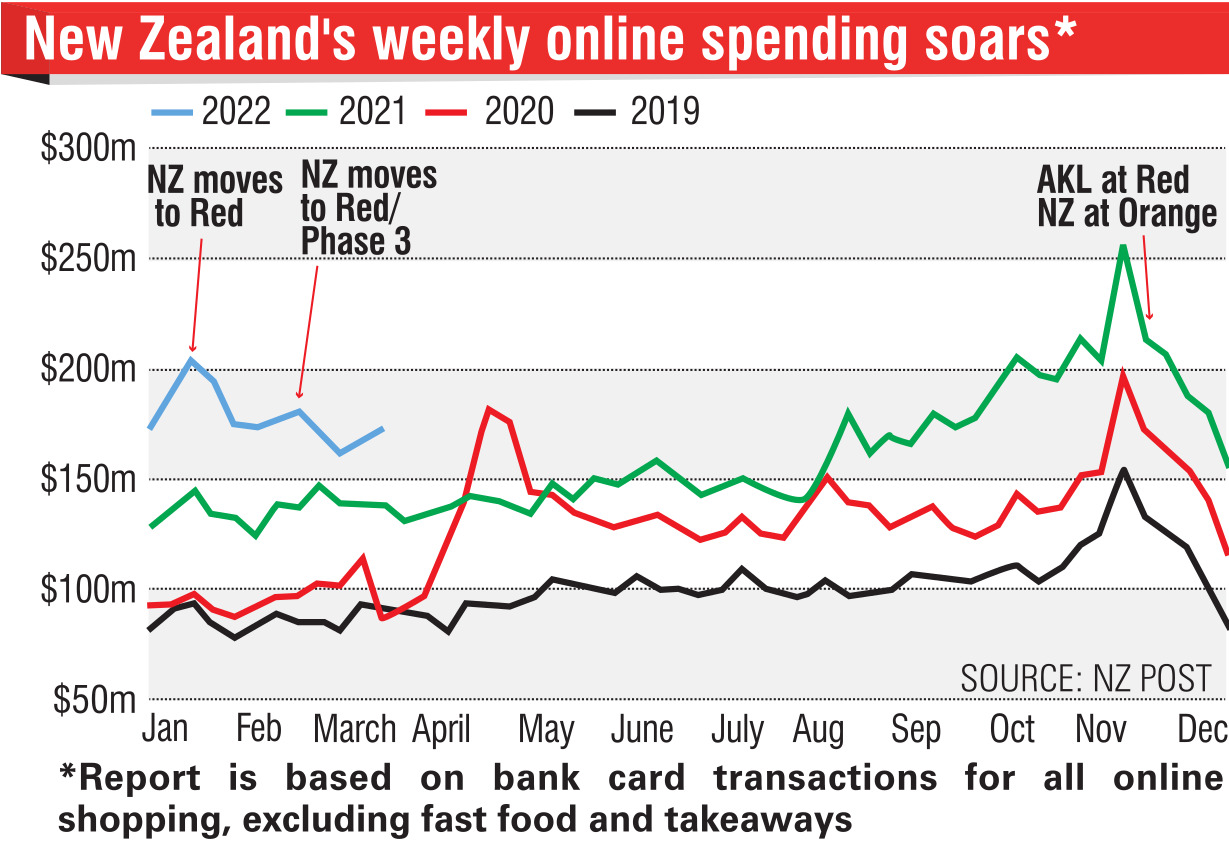

Lock downs, tiered levels, traffic lights ... New Zealanders’ consistent response to the pandemic’s perpetual public safety permutations has been to hunker down and click "cart".

In just three years, Kiwis’ online spending has more than doubled.

New Zealand Post’s latest online shopping review shows that in the first quarter of this year New Zealander’s spent more than $2.2 billion on physical goods online. That includes groceries, appliances, clothing, health and beauty, but does not include spending on online services, media, fast food and takeaways. For the New Zealand picture on those, global statistics for the likes of UberEats, Expedia and Booking.com give at least some indication of scale and reach.

Booking.com’s revenue is almost back to pre-Covid levels, with revenue of $14.64 billion in the past 12 months. Expedia’s global revenue in the past year was $9.6 billion.

The pandemic was a ski ramp rather than a speed bump for Uber Eats. The platform’s revenue soared from $4.8 billion, in 2020, to $9.8 billion, in the past 12 months.

Kiwibank chief economist Jarrod Kerr says the pandemic has condensed a shift online, which was expected to take up to a decade, into little more than one year. And he expects more change to come.

"We will see online retailing explode ... It’s going to get faster," Kerr says.

The positives are obvious. Convenience, time saving, comparing competitors’ prices and savouring myriad offerings — all from the comfort of the couch.

Yet, while we have embraced online retail avatars as our new "besties", many have not acquainted themselves with the beating heart, let alone the digestive, reproductive and waste disposal systems, of the entities they clasp.

Take, for example, UberEats.

It is by far the most popular of the four ready-to-eat food delivery and pick-up platforms to which Dunedin restaurant owner Suryamani Anthwal subscribes.

Did you know that online orders for curries from his two restaurants, India Gate and Indian Spice, now account for 65% of his total business; Uber Eats alone making up half his weekly orders? (And Uber Eats is equally important to most of the other food retailers Anthwal knows.)

Do you realise each platform has its own ordering system, requiring Anthwal to keep a constant eye on four different devices?

Were you aware that 30% of the menu price you pay when ordering one of his tasty curries through Uber Eats goes to the delivery company, and that the fee taken by most of the other online platforms is about the same?

Had you noticed five Dunedin Indian restaurants closed their doors this year, forcing Anthwal — due to the increased subsequent business in tandem with severe labour shortages and the bottom-line impact of online fees — to increase his prices?

Still, Anthwal does not have a bad word to say about UberEats or any of the other online platforms he now depends on for his livelihood.

Others close to the industry, however, are happy to criticise, but not on the record.

"Uber[Eats] is taking away a chunk of money from their turnover, straightaway," someone says plainly.

One person is highly critical of the Uber Eats practice of holding the money earned during the week and paying it to the food retailer the following Tuesday.

The retailer does all the work, bears all the costs, watches all the meals go out the door, but does not get paid until up to a week later, less the fee, he says.

"So, basically, you are working for them."

UberEats is a platform monopoly, which is not a good thing, Assoc Prof Trent Smith believes.

"Just like Amazon, they put themselves between the customer and the restaurants. And that gives them the same sorts of power that Amazon has," the University of Otago economics researcher says.

"With UberEats, the scandalous thing is ... they charge this enormous fee, which is essentially the fee for delivering the customer."

Platform monopolies, by making themselves the middleman, get to take a big slice of the pie for providing a service that costs virtually zero per new customer, Prof Smith says.

"That is bad for society at large because there are many transactions that don't take place because of this price wedge between buyer and seller.

"It's like having a 30% tax on every booking you make."

UberEats would say it is good for the economy. In fact, it commissioned a report from the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research consultancy assessing its impact.

That report, released in September, 2020, estimated UberEats contributed $162 million to the economy each year and was responsible, on average, for $59,600 of each participating restaurant’s annual revenue, in 2019.

Prof Smith, however, questions whether it is good for the restaurant sector or the country.

"As more and more restaurants adopt the service, the competitive advantage it conveys will necessarily shrink, and to the extent that restaurant costs rise (for example, because UberEats fees exceed what a restaurant would normally spend on promotion and delivery) you would expect this to be passed on in higher prices to the consumer.

"In the long run, you can expect profits to flow to overseas investors."

This is not just about UberEats and the ready-to-eat meals sector. It is a broad concern about the way the shift to online shopping is enabling potentially harmful platform monopolies across all retailing, including tourism and perhaps even groceries.

Dr Rob Hamlin says Expedia and Booking.com have already established what is effectively an online duopoly in the hotel and holiday home sector.

"About 90% of all hotels in Queenstown are now booked through those two websites," the University of Otago marketing researcher says.

"Expedia and Booking.com [fees] start at 15% and go up from there. So, the margins these people are making are absolutely enormous."

And the duopoly is more watertight than it might appear, because both companies own various other similar entities.

Expedia Group’s websites include Expedia.com, Bookabach, Trivago, Wotif, Vrbo, Hotels.com and CarRentals.com.

Booking Holdings’ websites include Booking.com, Agoda, Kayak, Cheapflights, Rentalcars.com, Momondo and OpenTable.

Expedia and Booking.com are now so strong they can demand hotels not offer a lower price than theirs’ on any internet channel, Dr Hamlin says.

He does not believe New Zealand should allow this.

"What is the point of covering this country with concrete and tour buses and motels just for the profit — and 15% does represent nearly all of the net profit — to end up in the the headquarters of Expedia and Booking.com?

"We're just going to end up having all of the downsides and nearly all of the profits will go straight overseas."

Dr Hamlin thinks traditional supermarkets could also be in for a nasty shock.

They have made an effort at online offerings — click and collect or delivery options — but he rates them half-hearted efforts done mostly for the sake of appearances.

"Supermarkets fundamentally don't like the internet because they recognise, correctly, that the internet is a major threat to the basis of their power."

He suspects e-commerce multinational Amazon.com — which along with Facebook, Google and Apple is embroiled in monopoly investigations in the United States (US) — could plan to make good on that threat.

Amazon has been opening physical grocery and convenience stores in the US, and now in London, too. The stores have no cashiers; goods are recorded and paid for via app.

Dr Hamlin thinks the stores are not so much a commercial operation as a data-gathering project.

"I believe Amazon will now have more data, and better data, on how people shop in a supermarket than almost anybody else on the planet.

"That information could be used to develop an online platform for a supermarket that might well start to seriously challenge the current bricks-and-mortar format."

In response to questions from The Weekend Mix, an UberEats spokesperson said while weekly payments to merchants were the default setting, merchants could use their portal to make it daily.

The delivery option has a fee of up to 30%, but self-delivery and pick up options have fees of 16% and 6% respectively, they said.

The company’s spokesperson did not respond directly to questions about the fairness of its fees or whether its market share was benefiting neither sellers nor consumers.

“The rise of online ordering and delivery has given Kiwis more flexibility when it comes to how and where they choose to spend their time," the spokesperson said.

"In addition, the more than 3000 restaurants, cafes and other merchants on UberEats across Aotearoa have flexibility in choosing how and when they partner with us to help drive additional demand for their businesses."

The Mix asked Expedia how it justified its fees.

A response from a spokesperson said the "compensation paid by our partners covers every aspect of marketing and customer acquisition", making Expedia Group "one of the most cost-effective means for hotels to help fill their rooms".

A similar question was emailed twice to Booking.com’s London press office. No response was received.

Prof Smith says the Commerce Commission should "limit these these kinds of pricing abuses from these platform monopolies".

Dr Hamlin says New Zealand should take more drastic action.

"I'm a very strong supporter of this country actually offering a national booking platform for its hospitality ... and doing it at cost, [which] will be about 1%."

He cites the example of Columbus, Georgia, in the US, which tried to tax Expedia and Booking.com and promptly had every hotel in the city de-listed by the two booking platforms.

Columbus, Georgia, he says, thrived.

If people want to go somewhere, they most-often search the name of the place online and the search engine will put Expedia or Booking.com high on the results, Dr Hamlin explains.

"But if Expedia and Booking.com don't have anything on Columbus, what comes up is the hotels’ websites.

"So ... New Zealand does not need the booking agencies. People who want to come to New Zealand will Google ‘New Zealand’, they will not Google ‘Expedia’.

"If you get rid of [the likes of] Expedia, then it won't affect tourism apart from the fact that the 15% they are sucking out of every single accommodation transaction — and increasingly entertainment and dining and vehicle transactions as well — doesn't leave the shores of this country in their direction."

Dr David Clark, Minister of Commerce and Consumer Affairs, wants the Commerce Commission to take any necessary steps.

He says online platforms make it easier for consumers to shop for a greater variety of goods and services. He believes competition is the best regulator of price.

"With that said, these businesses must comply with the Commerce Act 1986 and Fair Trading Act 1986," Dr Clark told The Weekend Mix.

The Government has recently amended the Commerce Act to strengthen the prohibition against misuse of substantial market power.

"I am keen to ensure the Commerce Commission has the tools and capability necessary to intervene if required to protect the interests of New Zealanders."

Kirt Gandhi, while doing his UberEats deliveries, has come up with another solution.

The Government could take on the UberEats franchise for the whole country.

It would, he says, be a win-win for everyone. The laziness issue, no doubt, is somewhere in the mix.

"They should have a programme like this ... and employ all our people who cannot work full time or who are not even ready to work full time.

"If they take the franchise for New Zealand and run it properly. You get my point? The Government gets this much money in their bank. And they are helping the people. They're helping the drivers. They're helping employment, everything."