Days from retirement, Lou Sanson is no less enthusiastic about the beauty and power of New Zealand’s natural heritage than he was as a boy exploring West Coast valleys half a century ago.

As director-general of the Department of Conservation, that passion has intersected with some of the most important issues of our time, writes Bruce Munro.

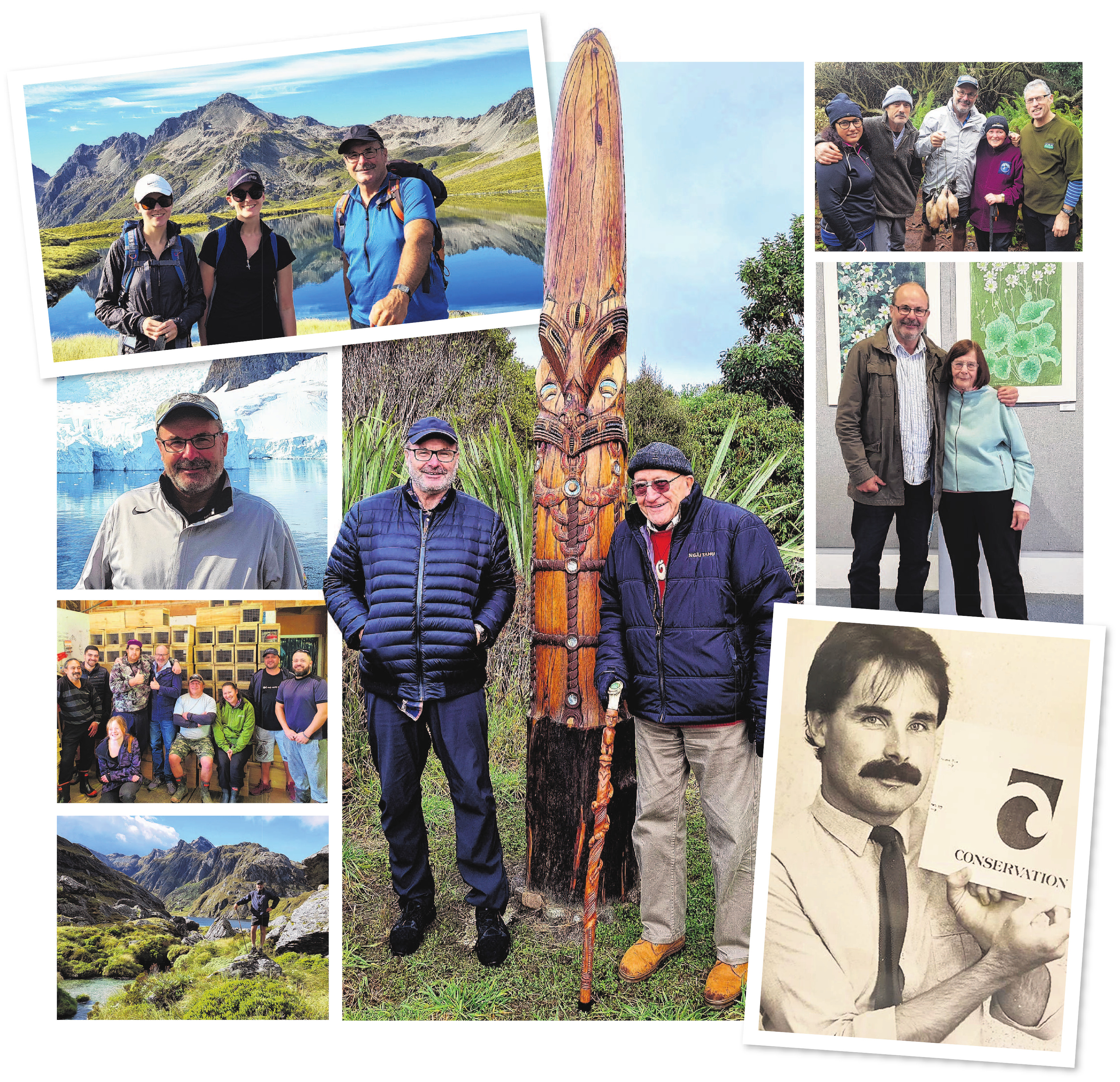

Clockwise from top left: Department of Conservation director-general Lou Sanson with his two daughters, Georgia and Stephanie, at Lake Angelus, Nelson Lakes National Park, December, 2017; Sanson and Sir Tipene O’Regan standing with a pouwhenua carving on Whenua Hou, Codfish Island, July, 2021; Karina Davis-Marsden, Rewi David, Lou Sanson, Jane Davis and Tane Davis on the titi island Putahinau, in 2018; Sanson with his mother, Alison, at the Hokitika Alpine Flower Art Exhibition, November, 2018; Sanson displays the newly formed Department of Conservation’s logo, in 1987; Sanson stands in the Valley of the Trolls, Aspiring National Park, January, 2019; Sanson with Jobs For Nature workers, Paungaru, Hokianga, July 2020; and, Sanson at Paradise Bay, Antarctic Peninsula, January, 2013.

Lou Sanson is speaking by phone from his home office in Miramar, Wellington.

In a week’s time, aged 64, having spent most of the previous month barred from his downtown office by New Zealand’s second nationwide Covid-19 lockdown, he will step down as director-general of the Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai (Doc).

It will be eight years since he took the job heading up the nation’s natural wildlife conservation, responsible for a third of New Zealand’s land area, about 8million hectares of alpine zones, native forests, national parks, wetlands, lakes, marine reserves and offshore islands.

It will also mark more than three decades of his leadership in significant environmental roles with responsibilities stretching from the Kermadec Islands, 1000km northeast of Cape Reinga, to Scott Base, in Antarctica, 3500km south of Bluff.

And it will be 51 years since he decided Aotearoa’s awe-inspiring natural environment would be his life’s work.

In 1970, at the age of 13, Sanson was tramping with his mother in the mountainous Kelly Range-Styx River area of the West Coast.

"I saw some Forest Service survey people at Harman Hut," Sanson recalls.

Already drawn to the outdoors, these men, in charge and in their element, seemed to Sanson powerful and appealing.

"I thought, ‘Wow, that’s what I’d like to be when I grow up’."

During his time heading up Doc’s Southland Conservatory, as chief executive of Antarctica New Zealand and then as boss of Doc nationwide, Sanson has been involved in Treaty of Waitangi claim settlements, climate change research, improving workplace safety, ecological restoration and Maori-Crown partnerships, all through the lens of helping New Zealanders find their place in the natural world.

"I think nature sits at the very heart of who we are as New Zealanders.

"Every day I go to work excited and feel just so privileged to have worked for New Zealanders on the most incredible assets in the world."

Sanson’s childhood and teenage years were spent in Hokitika. His father, Trevor, who died in 2003, was an engineer who loved Antarctica. His mother, Alison, now 90 and still living in the family home, is an artist who loves the Southern Alps.

Sanson imbibed both passions — one at a distance and one every day.

Between the ages of 12 and 17, he explored every valley between Hokitika and Haast.

"At the age of 15 on the Coast, you had a rifle, a driver’s licence, you’d shot your first deer, learnt how to cross rivers, how to cook in a camp oven.

"The experience of growing up on the Coast ultimately led me to this job ... I just feel so proud to have grown up on the Coast."

His first paid job was track cutting up the Copland Valley. At 17, he was accepted into the Forest Service as an environmental forester. A University of Canterbury forestry degree was followed by two years at the Forest Research Institute and several years’ work that furthered skills in forest surveying, pest management and visitor planning.

In 1987, the massive restructuring of New Zealand’s public service saw Sanson become the Southland District Conservator of the newly established Department of Conservation, at the tender age of 30.

"I had quite a heavy research background. I’d done a lot of fieldwork, a lot of track work and survey work.

"I don’t think there’s many places in New Zealand you could become a manager at 30 ... but Invercargill gave me that phenomenal opportunity.

"I think that was the break that gave me the leadership skills."

It was also where he met his wife, Jan, and where their two girls, Georgia and Stephanie, were born.

"I went to Invercargill for six weeks and stayed 22 years.

"I just loved Southland — the incredible diversity of landscapes, the fantastic people."

The beginning of that role also marked the start of what has become a "really deep relationship" with Ngai Tahu.

"As we set up Doc I got involved in the Ngai Tahu Treaty Settlement.

"I was the one working on the Crown Titi Islands and Whenua Hou, in terms of giving them back to Ngai Tahu."

Although not directly involved, Sanson found the 1995 Cave Creek disaster — that killed 14 people when a viewing platform in Paparoa National Park collapsed — extremely challenging.

"I remember just feeling so depressed and overcome with grief, as an employee of Doc, about what had happened."

Cave Creek, Sanson says, was a failure of systems.

"That became a period of growth during which I learnt about leadership of large organisations, as a result of those tragic fatalities.

"What I saw was incredible growth in the department as we took safety and systems leadership seriously."

What followed was some of his proudest work — setting up Rakiura National Park and the Sub-Antarctic Islands World Heritage Area, starting eight Marine Protected Areas in Fiordland and, during his last year in the role, being able to announce that Campbell Island was predator-free.

"For six years, it was some of the most challenging and satisfying conservation achievements, through working closely with Ngai Tahu and the Southland community."

In 1981, Sanson had loved every moment of five months he spent in the Antarctic as a field assistant. He was rapt when, in 2002, he got the chief executive job at Antarctica New Zealand. The role meant overseeing the country’s interests in Antarctica and the Ross Sea, running Scott Base and providing logistics support to the 500 people involved in scientific research on the ice.

During the next 11 years, based in Christchurch, he was involved in setting up the McMurdo Dry Valleys Antarctic Specially Managed Area and the Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area. He also led New Zealand’s biggest climate change research project, the $35 million multinational Antarctic Drilling Project, which has led to predictions about sea-level rise in New Zealand and the Pacific.

The safety lessons from Cave Creek were applicable in the Antarctic. During his last year, overseeing 500 people working in one of the world’s most hostile environments, there was only one accident, and that in a gym.

The value of relationships was the biggest learning from those years.

"Ultimately, it’s all about the power of relationships.

"Jan and I put an awful lot of effort into hosting so many people that constituted both the Antarctic community and the New Zealand conservation community. Without those relationships you never really get to the partnerships.

"That’s been my modus operandi as director-general of Doc — knowing how important relationships are to getting long-lasting gains in conservation."

The foremost challenge Sanson set himself when he took up the director-general role in 2013 was extending the safety culture at the department.

"I was adamant that no person working for me should get hurt.

"Very sadly, on my watch, I have had five deaths."

In December, 2014, Stewart Haslett, a Doc Aoraki Alpine Rescue Team member, fell to his death while climbing on the north side of Mt Cook’s east ridge.

The same month, three years later, Doc volunteer hut warden Calvin Lim fell to his death while tramping on Mt Somers.

In October 2018 Doc staffers Paul Hondelink and Scott Theobald and helicopter pilot Nick Wallis died when their helicopter crashed after it took off from Wanaka airport.

"As a chief executive you live with those deaths, those funerals, those relationships all your life."

It led to a re-doubling of safety efforts.

Sanson believes the change in safety culture at Doc is one of his "great legacies".

"I took some big calls, like banning the use of Robinson helicopters. I banned the use of all-terrain vehicle quadbikes. And at one stage I stopped the entire Department for a day so that everyone at every location sat down and said ‘What can we do to stop hurting people?’."

Looking back at what has been achieved, Sanson says the key to successful, ambitious initiatives is working out the mood of the nation.

"The trick of government policy is to catch the wave, not move against it."

Restoring back-country huts is one such initiative with enormous public goodwill.

The Predator-Free 2050 campaign has been another of those massive social movements, catalysed by Sir Paul Callaghan and given leadership by the likes of Sir Rob Fenwick and Gareth Morgan.

"It’s just been so exciting to see ... the thousands of New Zealanders involved in that vision every day, be it on Rakiura, Okarito, Otago Peninsula, Banks Peninsula or Waiheke Island.

"I think nature sits at the very heart of who we are as New Zealanders.

"People want their birds back and they want Papatuanuku thriving."

Some question whether the goal can be realised by the date set. But not Sanson.

"It is fantastic to have a vision to shoot for — something that feels so hard, so difficult.

"At current technology you can’t do it. But ... I think we are just on the edge of the next great technology revolution.

"By 2050, this country will be the Galapagos of the world, in a world that is rapidly losing biodiversity. In my view, it is the single biggest change to New Zealand’s balance sheet that we could ever make, to restore our biodiversity."

Ssanson is proud of Doc’s tourism infrastructure and of the relationships the department has developed with some of the country’s largest commercial entities and philanthropic organisations, which have resulted in a $100million investment in conservation.

He is also pleased with the way he and Doc have delivered on different political expectations. Sanson has been Doc’s director-general during the term of four Ministers for the Environment.

"My job is to implement the conservation vision of the government of the day."

He agrees those visions varied.

"But what stays the course is things like restoring biodiversity, predator-free and how we look after visitors."

Despite saying he is excited to go to work every day, Sanson readily concedes the job has, at times, been difficult.

The helicopter crash was "incredibly tough". So too, in a different way, was Doc’s 1080 pest poisoning programme.

"1080 and landscape-scale conservation would probably be some of the hardest work I’ve done."

Synthetic sodium fluoroacetate, known as 1080, is a metabolic poison. New Zealand is the largest user of 1080.

"We know not everyone will agree with it, but for large parts of new Zealand it is our only way to restore some of these incredible landscapes that we have."

Doc staff involved with 1080 aerial drops received death threats and Sanson was personally threatened. "I’ve lived with the attacks myself, and through the eyes of staff who have had wheel nuts loosened on vehicles, or their windows smashed."

In 2016, a person was sent to prison for more than eight years for threatening to poison infant milk formula if the Government did not stop using 1080.

Sanson believes Doc has shown 1080 can be used to make a real difference.

"Right at the moment, we don’t have any other technology.

"We’ve learnt to use it at lower doses. We are incredibly careful with it.

"We’re seeing dramatic results in places like South Westland and Kahurangi National Park, where we are seeing completely new bird populations in places they didn’t exist."

Sanson is not sure what comes next for him personally.

He would like to do service as a director on some boards. In the meantime, he plans to help paint some back-country huts, lay some stoat lines in the Matukituki Valley, do some ski touring and mountain biking and walk a chunk of Te Araroa trail.

"I’ve got plenty more to contribute. I’ll definitely contribute in conservation or climate change or the science environment area."

Looking backwards and forwards from the cusp of an active retirement, Sanson says Maori mentors have played a big part in his career and that Doc’s Treaty partnership points the way to a bright and distinctive future for New Zealand.

Respected Ngai Tahu kuia, elder, Jane Davis was his first mentor.

"She encouraged me to do all the predator-free islands around Rakiura and Whenua Hou, that has led to the kakapo programme."

Others have included Sir Tipene O’Regan, chairman of Ngai Tahu Maori Trust Board, the late Piri Sciascia, chief adviser to the Governor-General, the late Waana Davis, chairwoman of Toi Maori Aotearoa, and Sir Chris Mace, commissioner of the Tertiary Education Commission.

"From first meeting Jane Davis, in 1987, these people have been really strong mentors, wanting me to succeed.

"And it has just been so much fun meeting so many other iwi leaders who are passionate about the work we do in conservation."

If people accept that being a New Zealander is fundamentally about a relationship with nature, and if they realise the Maori world view is a kinship-based relationship with the natural world, then the Treaty partnership can offer something powerful, Sanson says.

"There’s some real magic in what we can do as a nation to use our Treaty relationship to have an indigenous-inspired Western democracy that recognises the real strength of this country is having this multicultural approach to deciding how the country should run its affairs.

"It’s about Aotearoa New Zealand and tikanga Maori and the basic premise that if you look after nature, nature looks after you."