From white cats to antique furniture or evening bags, Catherine Chidgey cannot resist collecting them.

The award-winning author believes this ‘‘collecting gene’’ she has makes her a perfect candidate to tutor at a new writing festival at Olveston in Dunedin.

‘‘For me that love has always been tied to thinking about stories attached to those objects.’’

So tutoring in a historic Edwardian home full of period treasures and encouraging writers to get inspired by an object from it is a ‘‘natural fit’’.

‘‘It’s a great idea.’’

Hamilton-based Chidgey is one of the writers taking part in the ‘‘The Great Write Inn, weekend for writers’’. Others leading sessions include Emma Neale, Dianne Brown, Bronwyn Wylie-Gibb and Emily Writes, Fiona Farrell and Amy Scott.

Chidgey, who will be zooming in due to Covid restrictions, loves Olveston, remembering visits to it when she lived in Dunedin.

‘‘It’s such a special place, a gem for the city to have and how fantastic to have a writing event there.’’

In her session she will be sharing stories about objects that are important to her.

‘‘There are a few objects that have been really important to me in my writing, objects that ended up being really central to my two Germany novels and symbolically important to those novels.’’

Another important object that sits on her desk is a fossilised crab, a new species her grandfather discovered in the 1960s.

‘‘I used the imagery of fossils in my first novel, which features a character based on my grandfather, to talk about chipping away at the surface matter to get to the treasures that lie beneath.’’

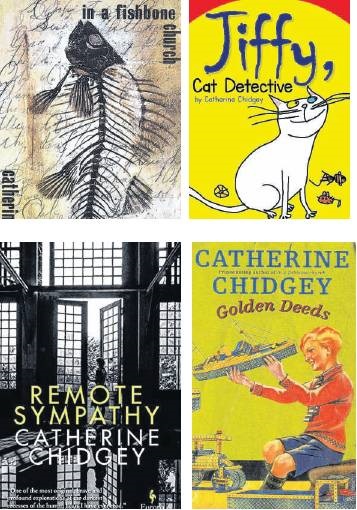

It is advice new writers will lap up given Chidgey’s debut novel In a Fishbone Church, won Best First Book at both the New Zealand Book Awards and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize (Southeast Asia and South Pacific). It also won the Betty Trask Award (UK) and was longlisted for the Orange Prize. Her second novel, Golden Deeds, was a book of the year in Time Out magazine (London), the LA Times Book Review and the New York Times Book Review.

Her fourth novel, The Wish Child, was an instant bestseller, winning the Janet Frame Fiction Prize, the Nielsen Independent New Zealand Bestseller award, and the Acorn Foundation Fiction Prize while her latest novel Remote Sympathy was shortlisted for the 2021 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Chidgey juggles writing with teaching at the University of Waikato and at the moment the organisation of the prize-giving for the Sargeson Prize short story competition - New Zealand’s richest short story prize which she founded - around Covid-19 restrictions encroaching on Waikato.

‘‘It’s a bit of a scramble. What could possibly go wrong?’’

She is also suffering from a frozen shoulder which restricts her movement and causes pain. It is also impacting on her ability to write the way she is used to.

‘‘I’m having to train myself to use Dragon dictation software but it’s counterintuitive to the way I work.’’

Her usual practice when writing is to use a keyboard, editing as she goes.

‘‘I’m changing things around so much, every single sentence. It’s a messy way of writing and exactly what I tell my students not to do.’’

Thankfully, she is on to the editing stage of her latest novel which is not so intense.

‘‘It’s not in that generative stage when I have to produce 500 words a day. Editing is a bit easier.’’

Now having cortisone injections to help manage the pain, she is doing her best to deal with the condition which can take a few years to resolve and trying not to think every twinge she feels in her other shoulder is the onset of another frozen shoulder.

‘‘My friend Kate Camp, a poet, has a frozen shoulder at the exactly the same time I do, which is weird as we came through the creative writing course at Victoria together and published our first books around the same time. It’s kind of spooky.’’

The novel Chidgey is editing at the moment is as far away from her previous novels around Nazi Germany as you can get.

‘‘I think I finally got Nazi Germany out of my system. I’ve sat with that dark material for two decades, I suppose.’’

Her new novel, The Axe Man’s Carnival, is set on a Central Otago sheep farm and features an unhappily married couple. One day the wife rescues a magpie chick and sets about raising it against her husband’s wishes.

The magpie begins to mimic human speech and becomes an internet sensation causing more conflict.

‘‘The bird is suddenly bringing in lots of money which could save their farm but the husband can’t stand the thing and thinks magpies are pests that should be shot.’’

The story is narrated by the magpie and writing it has been a joy for Chidgey.

‘‘It’s been a lot of fun. The bird is incredibly badly behaved and irreverent.’’

But how does one go from Nazi Germany to an irreverent magpie? Chidgey is not sure.

‘‘I honestly can’t remember. I was really ready for a change in scene and a change in pace.’’

There was the magpie she used to see from her home office window which looked out on rural land before it was gobbled up by a new subdivision.

Or was it talking to her husband, who grew up on a sheep station, about his experiences or reading his late mother’s diaries about the time?

‘‘It’s a weird organic process sometimes, where a novel comes from.’’

She is also fascinated by the fickleness of internet fame and how ‘‘everyone piles on the bandwagon’’ of the latest craze or famous pet.

It is here she states she has an admission to make.

‘‘Our cats have their own facebook pages and I sometimes dress them up.’’

Chidgey says it all began when they were living in Dunedin when they were semi-adopted by a white cat called Snowball.

‘‘He had a perfectly good home but liked to visit various others.’’

After they moved to Waikato and had an unsuccessful round of IVF they decided to get a cat.

They got a white rescue cat to honour Snowball and she had different coloured eyes - one blue and one gold - which is not uncommon in white cats.

Then the collecting gene kicked in again.

‘‘If we saw other white cats at rescues ... we ended up with five of them. They ended up as the Odd -eyed Pride on Facebook.’’

One also inspired a children’s book Jiffy, Cat Detective, and another Jiffy book which is due out next year.

Writing the children’s book had been a ‘‘lot of fun’’ and a great break from writing novels, she says.

‘‘It’s a very different process. Having that to turn to in between the much harder work of writing a novel is fun.’’

Chidgey admits there are not enough hours in the day to juggle it all.

‘‘I have an insane schedule. It is essentially two full-time jobs. So I have no other life, no social life and I’m usually in bed not long after 9pm.’’

Despite that she loves both.

‘‘They feed off each other. I love being around new writers who are learning the craft and who have that sense of wanting to take risks and try different things to figure out what they are good at or the kind of book they want to write - it is really energising to be around that.’’

It has also clarified her advice for new writers. The first thing is to show their work to other people.

‘‘Writing is a solitary act. It is very easy to isolate yourself and to get to the point with a piece of writing where you can’t see the woods from the trees, you can’t see what’s wrong with it.’’

All writers at all levels need to edit their work or have it edited, she says. For Chidgey it began with the creative writing course she did with a group that met regularly to talk about their work.

‘‘It’s been important for me. We kept meeting for years after the course finished. I still send work to Kate [Camp] and share by work with an amazing writing colleague Tracy Slaughter.’’

Chidgey also believes it is important to veer away from talking about big abstract ideas like grief, love or beauty and instead focus in on the small stuff to avoid the writing appearing vague or dissatisfying.

‘‘Focus on the small to talk about the big. Talk about really specific concrete details. Like writing about an object and use it as a jumping off point to talk about one of those big abstract ideas - like we will be doing at Olveston.’’

To see

The Great Write Inn is a Weekend for Writers: October 16-17