Sitting surrounded by her father Colin McCahon’s artwork The Wake, Victoria Carr reminisces about her childhood, remembering when writer John Caselberg’s great dane Thor used to bring her books (with a little help from his owner).

"They were regular visitors to our house in Christchurch. I was terrified of Thor — he was huge. However, I still have all those books Thor gave me. He always gave me a book."

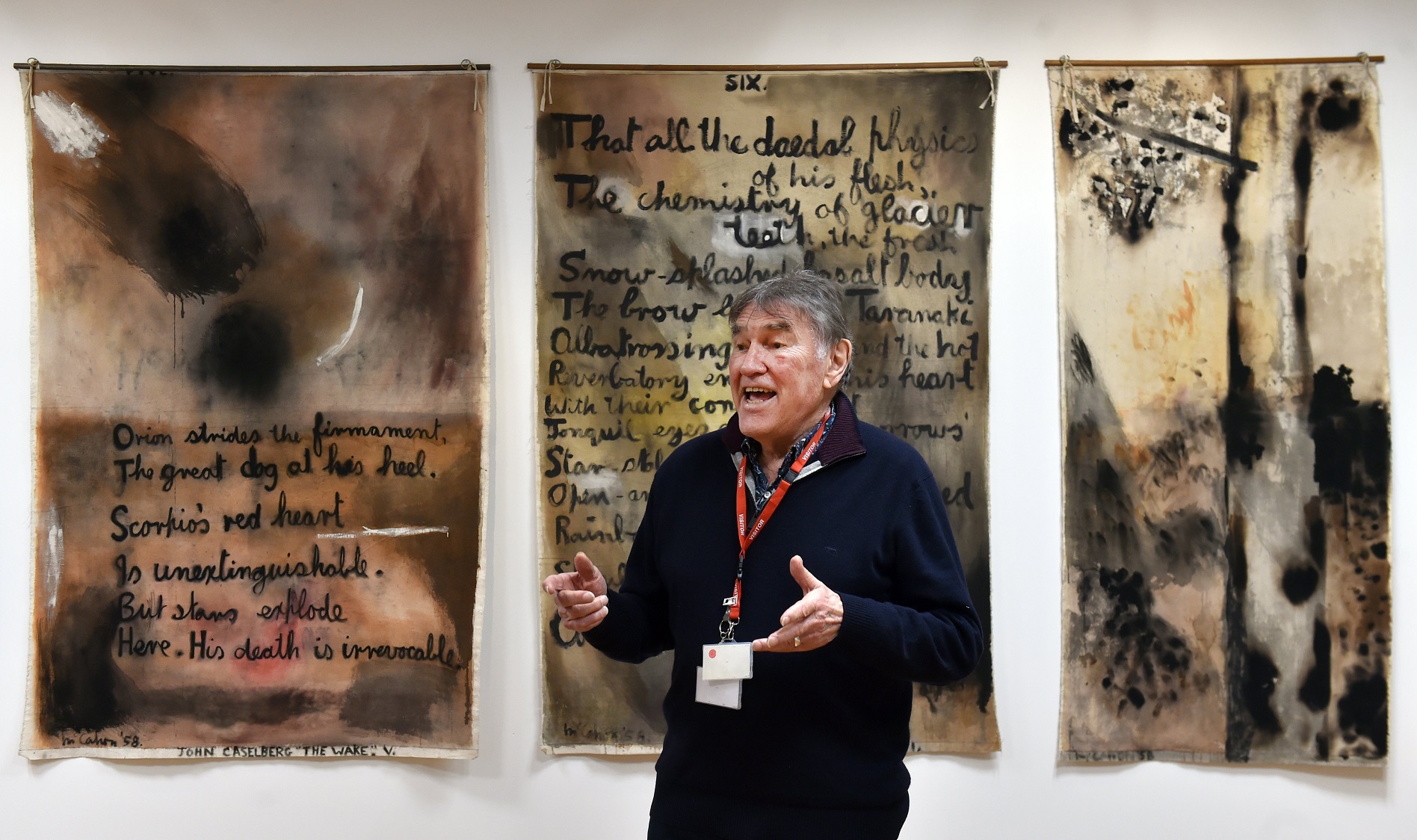

The Wake is based on a grief-stricken poem Caselberg wrote after Thor died and is hanging in its own space in the Hocken Gallery (as McCahon intended) as part of a new exhibition Artists and Letters, Pictures and Words.

"I grew up with a lot of these paintings. I remember all my life seeing these paintings. There were so many works in progress in the house. I’m thrilled with this — it is super to see this exhibition."

For her nephew and McCahon’s grandson, Finn McCahon-Jones, the experience of seeing the gallery’s walls dotted with McCahon’s life work has been "incredible".

On his first visit to Dunedin since he was a child, McCahon-Jones has found himself having a lot of "Colin moments" as he moves around the city seeing the landscapes that inspired many of his grandfather’s works.

"Coming here, I feel very at home visually. Feeling like you know this place through his paintings."

He was particularly pleased to see one of his favourite McCahon (1919-87) works, Caterpillar Landscape (1947), in the exhibition and have more light shed on the work by the transcription of letters between his grandfather and his friend and longtime supporter, librarian Ron O’Reilly.

The inspiration for the work was a map of the Lower and Upper Hutt valleys discovered by O’Reilly, which McCahon said he thought "summed up the valley very beautifully". However, his new work was unlike the valley but "very definitely of the NZ landscape" and the oval in the sky is the "Taieri Pet" as seen in the Middlemarch district.

There are many stories like this in the exhibition, as the letters McCahon and O’Reilly wrote to each other from the 1940s to the 1980s mainly concentrated on his art.

It is the reason McCahon scholar, Dr Peter Simpson spent many hours transcribing the letters for the recently released book Dear Colin, Dear Ron: The Selected Letters of Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly.

The pair met in 1938, in Dunedin, when McCahon was 19 and O’Reilly was 24, through their mutual interest in theatre; both were involved in WEA productions, McCahon as designer, O’Reilly as actor. They remained close, writing regularly to each other until 1981, when McCahon became too unwell to write.

In the exhibition the letters are being shown for the first time alongside works from McCahon’s early days as an art student and his first experiments in landscapes, as well as his figurative biblical paintings, abstractions, symbolism and text paintings. Many are from the Hocken’s extensive collection of his works, as well as from private and public collections around the country including Kauri Trees (1954) and Virgin and Child compared (1948).

"The centre of the show is the friendship between Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly. The thing about it is they wrote for so long. Right from the beginning Ron began to collect McCahon’s work, paying it off at 2 and 6 [two shillings and six pence] a week, but he kept collecting McCahon all his life."

For the book, Simpson transcribed nearly 400 letters. Some of O’Reilly’s were nearly 30 pages long, taking over a day to finish. O’Reilly’s handwriting was relatively easy to read but McCahon’s not so, he says.

"Sometimes you encounter words that take you a while to work out."

The letters show O’Reilly did not shy away from questioning McCahon about his work.

"He had his feet on the ground and was a dogged researcher and would question Colin closely about his work. The letters to O’Reilly are the most revealing about Colin’s own ideas about his paintings. You get closer to Colin the man and his real beliefs about life and art through these letters than any others."

There have been many stories revealed by the letters, including around his work Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1958-59 collection of Christchurch Art Gallery). It was completed after McCahon came back from the United States, where he saw the large works of artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. He moved to Auckland and abandoned figurative painting.

"It made a huge change to his work. He suddenly jumped up in scale, he started using house paints instead of traditional oil paints. He often didn’t frame his paintings and he started working in series."

Some people found that change hard to contend with. The work was to be exhibited in Christchurch and O’Reilly started a fund to buy the work to give to the Robert McDougall Gallery (Christchurch’s art gallery at the time). He wrote to Charles Brasch, McCahon’s most famous supporter, asking him to support it.

"Brasch was furious, saying it was completely irresponsible to rush into buying this work yet; we don’t know if any of these new paintings are any good yet and so on. There was a real standoff between the two great supporters, so they abandoned the scheme to buy the painting."

A couple of years later they started the campaign again and raised the money to buy it over the objections of the director of the McDougall.

"It finally became the first painting in the McDougall gallery and one of the earliest in any public collection in New Zealand. It is quite an important painting in the story of McCahon and O’Reilly."

O’Reilly had the ability to trust McCahon’s talent, thinking if he did not understand it now, he might one day.

"History has vindicated O’Reilly’s stance. That was what made him so remarkable. Although Colin was a challenge to everybody as he was such a radical thinker, O’Reilly had the ability to stay with him, whereas Charles Brasch stopped collecting McCahon in about 1958. O’Reilly kept on buying right to the end."

"Every McCahon is intense. Altogether it makes for something extraordinary, strong and powerful."

The letters have their visual analogues in the painting.

"Ron was an absolutely passionate exponent of McCahon’s art and a fellow struggler with it. It’s hard work, you have to put the time and energy in and it will be revealed."

Included in the exhibition is a grouping of works that usually hang on a wall in Matthew’s home. They have been hung in exactly the way they usually are at home and include a work McCahon did for him in 1973 after his wife died, featuring a stormy Muriwai.

"It is generated out of the relationship between Colin and Ron. He didn’t ask for the painting, I did, but Colin responded to me because he knew me."

When McCahon felt his public was against him, he took it to heart.

"It was vicious. He cared very deeply. He was very serious about everything really. He was a tough man. Yet he treated me so respectfully whatever my age."

He remembers going for a trip around Northland when he was about 18 with McCahon, who showed him the waterfalls he had been painting.

"That was really special."

The exhibition also includes a "study" gallery of works, co-curated by the Hocken’s Robyn Notman, of other artists with a connection to McCahon including his wife Ann Hamblett, student Robin White, teachers W.H Allen and R.N Field, mentor and friend Toss Woollaston and friend Rodney Kennedy.

"It’s his circle, his teachers, friends, students. At the centre of the exhibition is McCahon’s relationship with O’Reilly, because of the book, but it also includes his relationships with Brasch and Caselberg and beyond to the wider circle," Simpson says.

TO SEE:

Artists and Letters, Pictures and Words, until August, Hocken Gallery.