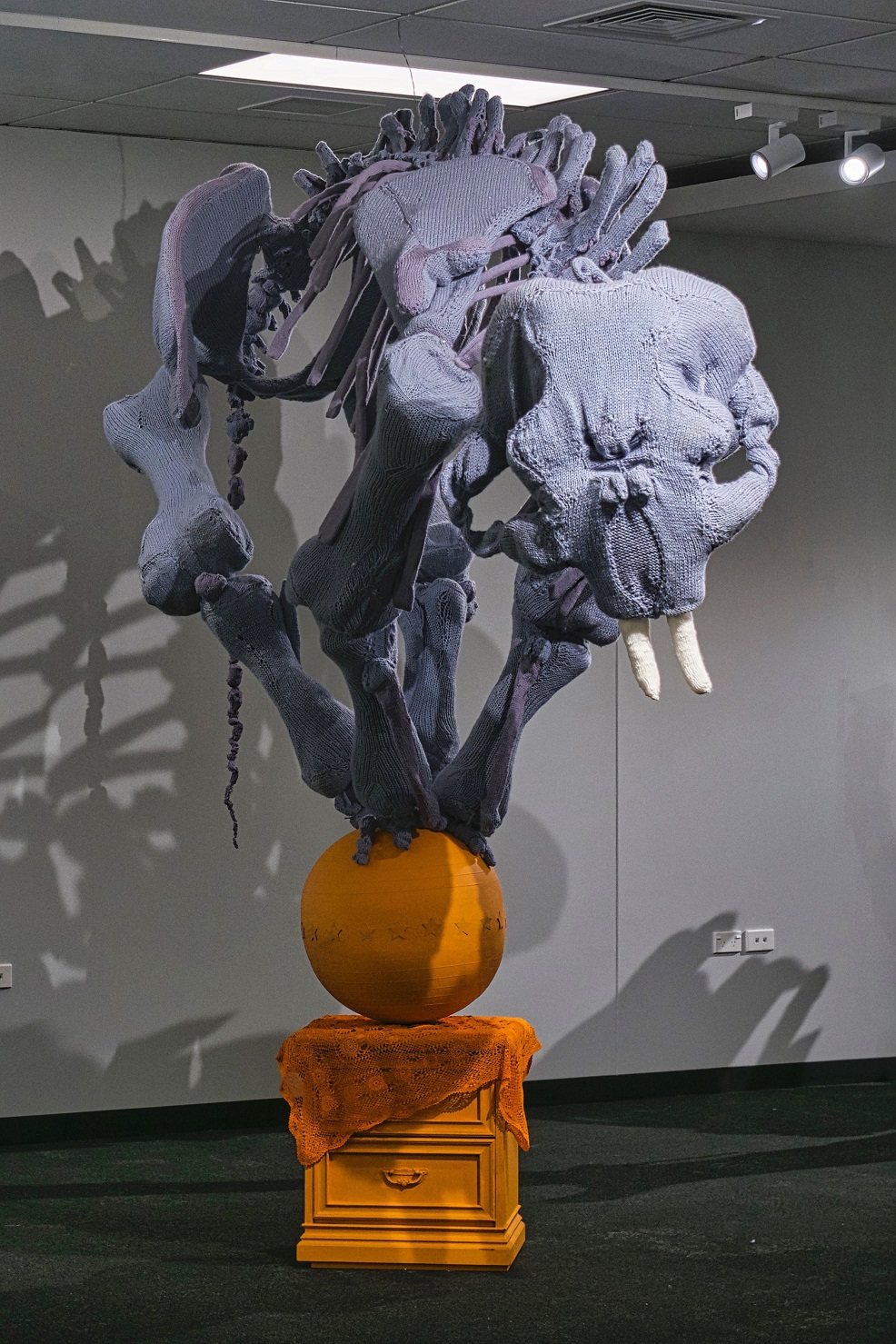

Her life-sized, knitted sculptures look soft and cuddly, yet to artist Michele Beevors they are a way to mourn for the lives lost and struggles many species face to survive.

"The works are an obvious reference to climate change and extinction rates."

On exhibit are 12 three-dimensional knitted animal species created by Beevors over the years including 50 tiny frogs, three gorillas and the three giraffes.

"The idea that in my lifetime elephants will go extinct — that kind of sadness. It feels like a hopelessness I can’t do anything about. But knitting is comforting in a way, when you give knitting in mourning it is a comforting thing."

It all began when Beevors, a sculptor and senior lecturer at the Dunedin School of Art, was standing in a craft and art supply store back in 2005 thinking she could probably knit a hat.

"Then I had an epiphany. I thought I could probably do something more complicated than a woolly hat because I was cold in Dunedin. The most complicated thing I could think of was a human skeleton. That was the genesis of the project really."

As she started knitting, she soon moved to the idea of animal skeletons, starting with a full-size horse which took about two years.

And so began her knitting journey.

"I knit every night and on weekends and during the holidays."

Her sculptural practice has always been on the large size. She believes it is to over-compensate for being a small person — she stands at 157cm . And her knitting is no different.

"I love large-scale sculpture but there is not that call for it here. I think scale is an important aspect of my work."

Asked if she enjoys it, Beevors says it is always a challenge and that is what keeps her knitting. She is always aiming to become better at it, faster and more efficient as well as creating better work.

"I like the problem-solving, it’s one reason I’m a sculptor and why I teach as well. Like doesn’t come into it. I don’t know what I’d do with my time."

There have been challenges, such as creating the three-dimensional patterns needed to structure the animals.

"That’s been the hardest. You have to think about the object as a whole so you turn it around in your head."

It has been a continual learning process for Beevors.

"You get better at doing things, at putting them together so that is more efficient so they last longer. So the pieces all evolve at once."

It took a long time to work out what wool to use so that it did not discolour overnight and how to reduce the amount of sewing needed.

"I don’t like sewing."

The inspiration for giraffes was the surprising discovery Tuhura Otago Museum had an adolescent giraffe skeleton. She spent three days measuring and sketching the skeleton before creating the pattern out of cardboard. It took about 70 balls of wool to make the big giraffe.

"I make the bulky bits out of whatever I have in the studio. They have an armature in them of course. Then I knit them a bit like a big sock."

For Beevors the works are also a reference to labour, the time and energy dedicated to knitting. The importance of labour is something ingrained in Beevors having watched her father work two jobs.

"It is necessary when you are knitting as you are counting off time one, two, three, four — the labour is evident in hand knitting and the labour is what carries the meaning, the care for individual animals, for the dead animals I have knitted. It is mourning their passing."

The soft, cuddly cute aesthetic generated by the knitting is a way for people to empathise with the works, she says.

"They can see the softness and the labour. The works hover between being serious and they have a muppet-like quality as well because of the soft sculpture. So they are funny, sad"

Being able to exhibit the works in the museum’s Animal Attic, a gallery of Victorian taxidermy, is pretty special for Beevors who has always had a soft spot for the gallery.

"The animal attic has had a sad fascination for me since I moved to Dunedin 20 years ago. I often take students there to draw and have gone there myself to draw.

" It has led me to research anatomical exhibits in Sydney, Paris and Vienna, to draw and collect data towards this exhibition."

It was while drawing the giraffe that Beevors talked to the museum about exhibiting the work in the place where it originated, as well as it being an opportunity to tell the giraffe’s story.

"It’s perfect in the museum. I can’t wait to see it. The curatorial team at Otago have been instrumental in helping me to discover some amazing things. So this exhibition is an amalgam of international stories of individual animals who lived and died in concert with humans."

Her love of animals goes back to her childhood in the suburbs of Sydney, Australia, where her family always had animals.

"We had dogs, cats, mice, birds, fish, we had a goat."

Pulling all the works together to exhibit has been interesting for Beevors who first drew up an exhibition proposal a few years ago.

The works have been stored in Beevors’ large studio where she lives at Aramoana with her artist partner.

"We have storage issues. But at the moment the studio is empty, yay. The first time in a very long time."

It is 20 years this year that Beevors packed up and moved to Dunedin to take up the teaching role at the art school.

"We’d been here ever since. The facilities are great and the people are great."

Being part of one of the last workshop-based art schools left is important to Beevors.

"I believe in making things so it’s perfect. It is important to make things and to think through objects and you are always learning."

The exhibit is not the end of Beevors’ knitting. She has plans for more and more complicated animals to knit such as a woolly mammoth and a dodo.

"The next show will be about extinct past animals and the one after that about birds. So I’ve got lots of knitting to do. I’ve got to get more complicated patterns going."

Museum curator, Natural Sciences, Emma Burns says the exhibition reflects on the world of collecting, of human impact, conservation politics and the sad realities of species loss and extinction.

"While the sculptured material is soft, the subject of the works is hard. Art is often able to hold these conversations in a different way to science."

TO SEE

Michele Beevors: Anatomy Lessons, Tuhura Otago Museum, April 9 — July 24

![... we all become all of these things [installation view] (2025), by Megan Brady.](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2025/03/1_we_all_become_all_of_thes.jpg?itok=nicA_yAm)