"Wild Gaia — The Halo of Life" celebrates the land, air, and water of the South in a series of large-scale impressions.

Kate Williamson has a dynamic style, created from rich dark colours presented in broad gestural strokes, out of which her scenes emerge.

The few figures in the scenes, human or animal, glow with an inner incandescence, a feature reflected in the "Halo" of one of the works’ titles.

As time has progressed, the artist’s images have become more based in representationalism.

Here it reaches its zenith in the tangled streams of "Braided, Sky River", in which an aerial view of a South Canterbury river recede into waves of magenta horizon, the individual channels becoming veins or strands of hair.

The land becomes Gaia, the earth goddess, the terrain breathing and stretching, her blood rolling down to the the sea.

Williamson begins by dripping and splattering paint on to her canvases, creating a raised surface texture over which she layers her images.

The ridges and blobs become integral parts of the scenes, catching the light to add luminous texture to works such as the threatening cloudscape of Wild Gaia Plight and the vague, mist-drenched slopes of Storm the

Seed.

(Olga)

We have a natural perceptual ability to recognise faces.

It is an ability that, while immensely useful, can be tricked into seeing faces where none are present, misinterpreting shapes as facial features.

This tendency is referred to by vision researchers as pareidolia.

Scott Eady explores this illusion in "Dross", a series of works created from discarded and found object which have been case in bronze, raising them above the level of the neglected ordinary.

The artist makes us look again at these overlooked objects, and in doing so to ponder both the hidden beauty of the forms and the wastefulness of a society which unthinkingly discards such items.

The exhibition finds its focus in a large installation, featuring bronzed brick rubble placed within a semicircle of graffitied panels which become the pulpit and stained-glass windows of a postmodern brutalist church.

A series of impressive smaller works nearby feature bronzed detritus on patinated steel plinths.

Two further works complete the exhibition: a video of an installation being used to perform a smash-and-grab turns the idea of art simply as art on its head.

Finally, a bronzed smiley face punctures the potential strait-lace of the exhibition, showing that none of the work is to be taken totally seriously, by artist or viewer alike.

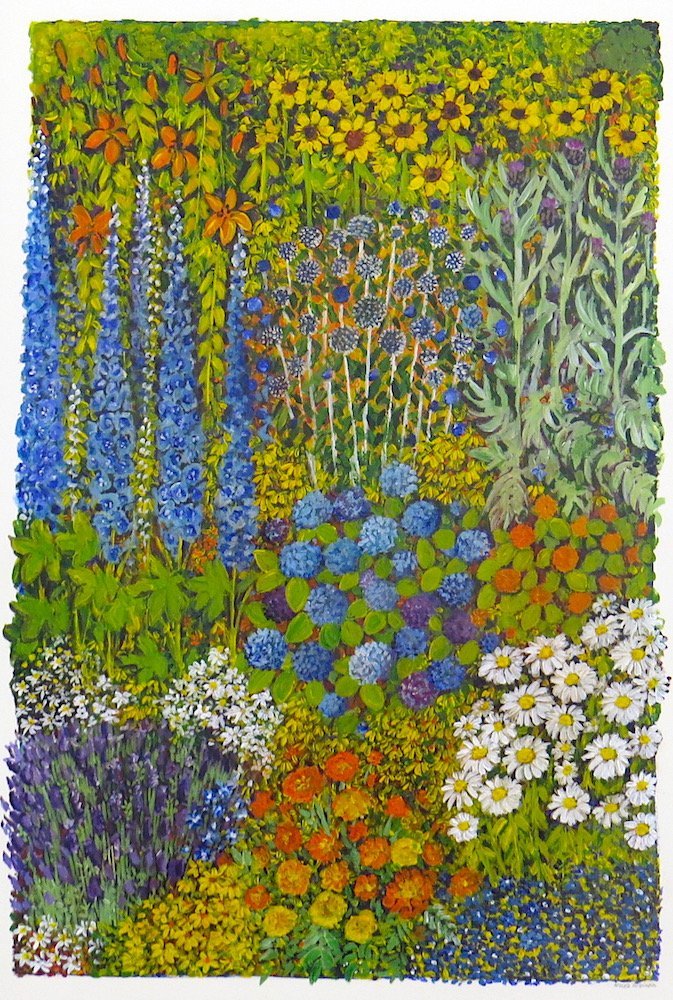

Maisie Robinson presents a series of densely worked floral scenes in her exhibition at The Artist’s Room.

The artist’s works show closely cropped flower beds in profuse bloom, the scenes deliberately reduced to flat, 2-D scenes.

As a result, attention is concentrated on the details of the flowers.

The resulting impression is reminiscent of the thick florality of Victorian wallpaper or early children’s book illustrations.

The wealth of colour seems to have a vaguely antique feel which well reflects the subject matter, the rigorous beauty of the cultivated garden.

A small touch of rebellion enters the scene with the uneven edges of the works, the flower seemingly ready to leap into the white spaces around the edges of the works.

An insight into the artist’s methods and compositions can be gained from the "We Had a Place in That Garden" works, presented both as initial studies and completed paintings.

Robinson has only recently move into the field of flower painting, many of her earlier works being of houses and suburban townscapes.

A few images of these subjects are present in the exhibition, including the impressive Parkhill View of houses on the slopes of Mornington.

Another image defies the deliberate flatness of many of the works with a leafy perspective-driven view of Olveston.

By James Dignan