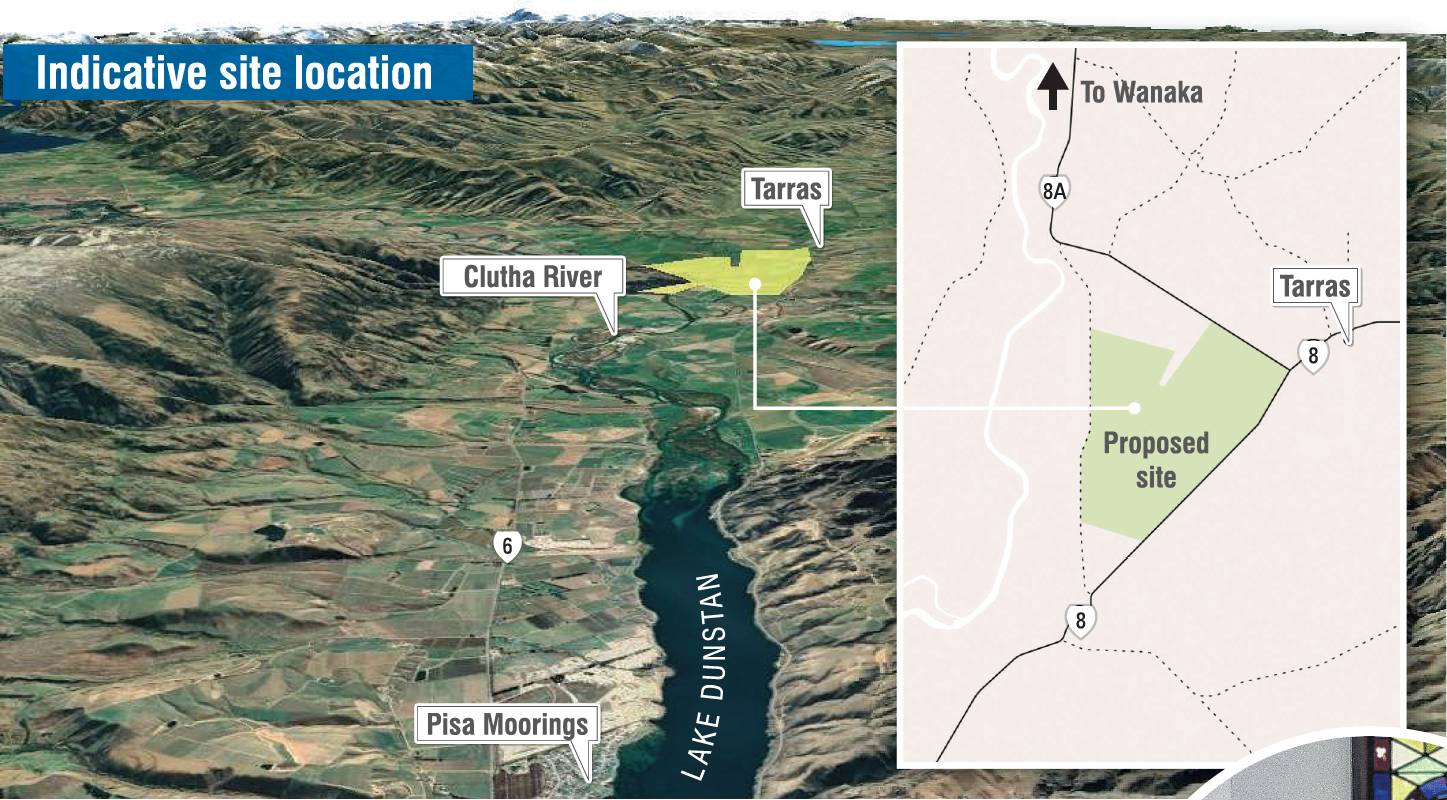

The recent public spat between the Queenstown Lakes District Council and the Christchurch City Council over 750ha of Tarras farmland has tweaked my interest.

Having got themselves embroiled in commercial activity, the councils, and the airport companies in which they are majority shareholders, must obey one of the fundamental imperatives of business life: effective competition.

The Commerce Act 1986 requires all businesses to compete.

The Queenstown and Christchurch airport companies cannot enter into discussions about rivalry between them, nor about how they could best divide up the airline services market in Central Otago or the South lsland.

The Queenstown Lakes District Council cannot say please do not enter "our" turf any more than Auckland University could have said to Massey University not to commence tertiary education at Albany on the North Shore.

This carries substantial penalties and will soon (from April 2021) incur criminal liability (and even up to seven years’ jail) for individuals deliberately implementing cartel arrangements.

It is true that section 36 prohibits monopolising conduct ("taking advantage of substantial market power") by powerful companies, but it is most doubtful that the potential entry of Christchurch International Airport Ltd (CIAL) into Central Otago is "predatory activity", as the Queenstown council charged.

This is competition at work, and unless CIAL engaged in predatory pricing (targeted below-cost pricing to drive out one’s competitors) itself a very difficult thing to prove, then the Queenstown council cannot complain.

What are the options?

Queenstown Airport Corp (QAC) might just call its erstwhile Canterbury rival’s bluff, sit back and wait for the Christchurch company to sink considerable time and expense going through the Resource Management Act hoops, not to mention the swathe of climate change protesters and nimby (not in my backyard) residents of tranquil Tarras.

Alternatively, the airport companies might decide to overtly co-operate to launch a new airport at Tarras.

Here there are two routes.

First, they may enter into a joint venture.

The Act (in section 31) allows for "collaborative activities" where the co-operative enterprise is reasonably necessary for the success of the project and its dominant purpose is not to lessen competition between the two parties.

This takes the arrangement outside the reach of the cartel prohibition, albeit the project is still susceptible to challenge under section 27, the general prohibition upon contracts, arrangements or understandings that substantially lessen competition in a market.

The other route is more comprehensive and protracted but affords full immunity.

The companies could apply for an authorisation from the Commerce Commission.

Here, the commission undertakes a sophisticated cost-benefit analysis to assess whether the "public benefits" from the proposed venture will outweigh the detriments from the lessening in competition.

CIAL has optimistically stated that the project "would provide significant social and economic benefits".

These would need to be substantiated, and it is always a hard row to hoe for applicants to satisfy the commission that an authorisation is merited.

Yet another option is the political pathway.

If the Government can be persuaded that competition in this important industry would be wasteful, or that a co-ordinated approach to New Zealand’s national airport infrastructure is better, then it can expressly state that the Commerce Act ought not to apply.

It has done this in various sectors such as shipping, dairy and electricity.

It has even done this for civil aviation: the Civil Aviation Act 1990 expressly states that levies paid to the Civil Aviation Authority are "specifically authorised" for the purposes of section 43 (the exemption section) of the Commerce Act.

The Government could pass another one-sentence amendment to the Civil Aviation Act to cover the sort of market allocation between airport companies that is contemplated here.

The quid pro quo to this antitrust law exemption would be close scrutiny of the new airport under the existing regulations governing "specified airport companies" set out in part 4, subpart 11 of the Commerce Act.

Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch airports are already subject to this cumbersome control of "specified airport services".

There is no doubt there is more water to pass under this troubled aviation bridge.

Meanwhile, the airport companies must continue to treat each other as rivals, and that means no discussions about curtailing competition, no collusion nor plans to divide up the market.

• Prof Ahdar’s latest book is The Evolution of Competition Law in New Zealand (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Comments

Quagmire indeed! The unintentional consequences of residents artificially restricting demand. Of course Christchurch City Council would want a share of global demand for Central Otago. They're rebuilding wealth since selling all their assets to fund their rebuild. Queenstown airport were totally guzumped!

Central Otago resides within an alpine archipelago of the southern ocean. Its prosperity is built on efficient global connectivity.

How our community leaders believe we could sustain prosperity and upward social mobility of our children, by trading off efficient transport infrastructure, for supposed 'quality of life' absolutely baffles me and is the height of selfishness.

The lesson here is, growth is coming, like it or not. The world will have another 600million middle class within 10 years, all within 10 hours flying time.

You cannot stop the incoming tide, better to channel it where you want it.