While the proposed revisions of the English curriculum in secondary schools have unnerved and offended some, there is perhaps one silver lining.

In a system seemingly intent on pushing students towards scientific and technical subjects, it is at least good to see literature can still create debate and controversy.

Details remain scant, but the curriculum rewrite would reportedly put more emphasis on traditional texts and teaching — more grammar, more Shakespeare and even more Chaucer.

Some have criticised the apparent secrecy of the curriculum review process and its prescriptive nature, and have questioned how relevant or accessible such authors might be for modern students in New Zealand.

But as the country’s only university academic specialising in medieval English literature, I want to explain how I teach Chaucer in the 21st century, and why the texts of "dead white men" might still be useful and relevant in the classroom.

When I’m teaching, I ask my students this question: why do they think we are studying Chaucer here at the end of the world, and what relevance could 600-year-old stories possibly have for us now?

In fact, Geoffrey Chaucer, who lived between about 1340 and 1400, has plenty to offer.

A radical poet in his day, he confronted medieval audiences with their long-held views of corruption in the church, obscenity, racism, anti-Semitism and sexual violence. Perhaps most famously, The Miller’s Tale (from Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales), depicts Nicholas’ rape of Alison. Chaucer describes how he "caughte hire by the queynte" — you’ll need to Google it.

The tale is still banned in some parts of the United States. And while in the past, students blushed and giggled at this passage, that’s not the case now. In a post-Trump world, they’re horrified.

If you studied Chaucer and don’t recall this episode as a depiction of rape, that’s understandable. It used to be taught as mildly risque and entertaining, despite the fact Nicholas "held her hard by the thigh", and Alison responded, "Let me be, Nicholas, or I will cry out, help!".

But Chaucer knew what he was doing. He challenged his audience to decide how to respond to such acts, even taunting "whoever does not want to hear it, turn over the leaf and choose another tale".

But by doing so, Chaucer implied, they were avoiding reality.

Chaucer — or how his work has been used — also has another contemporary relevance. In New Zealand, he was very much used as a colonising text. The first lectures ever given at Otago University when it opened in 1871 were on The Canterbury Tales. In fact, they were perhaps the earliest lectures on Chaucer anywhere in the world.

Otago’s first professor of English and classics, George Sale, said he hoped studying Chaucer "may have the effect of making us better citizens" in a new country.

Chaucer was simplified, translated, the obscene passages expunged, and used to instil a picture of an ideal world.

Some readers may recall learning how The Canterbury Tales show us a "slice of life" — if only the approved version.

Rather than relegating Chaucer to the past, studying his works helps us begin to acknowledge some uncomfortable truths about a colonial society.

Dunedin is also home to one of the largest medieval manuscript collections in the southern hemisphere, dating from the 10th to 16th centuries.

A motivation for collecting manuscripts was to better educate settlers in a way that valued European culture.

Charles Brasch, Esmond de Beer and Willi Fels — descendants of Bendix Hallenstein (1835–1905), the German-Jewish clothing manufacturer who came to Dunedin via Melbourne in 1873 — were devoted to collecting and donating artefacts to Tūhura Otago Museum and Otago University Library.

Similarly, Alfred H. Reed (1875–1975), the notable publisher and author, collected and donated a huge number of medieval manuscripts to the Dunedin Public Library, following his commitment to promote Christian values.

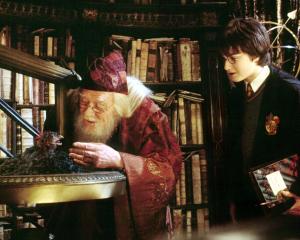

My students marvel at these medieval manuscript collections and the ancient books, with their intricate writing and gold illuminations.

But we also discuss the broader implications of this European heritage in a colonial nation.

When I look across to Otago Peninsula, I’m reminded of the 500-year-old waka recovered from Papanui inlet, now preserved at Ōtākou Marae.

I ask my students why artefacts of a similar age, both right here in Dunedin, have been valued so differently in the past.

Who decides one is more important than the other?

Chaucer’s works teach our students to question and challenge these aspects of their world.

Just as he challenged his medieval audience, his works continue to challenge ideas about New Zealand’s colonial past. — The Conversation

■ Simone Celine Marshall is a professor of medieval literature at the University of Otago.