First, that Māori never ceded sovereignty to the British Crown in 1840 and secondly that, when discussing the Treaty, only the version in Māori is valid.

Both declarations were issued from the Waitangi Tribunal within the last dozen years and have since been stated as certainties by those who oppose discussion of Treaty "principles".

The tribunal is a kind of Star Chamber for Māori, but Parliament and government are not obliged to act on its conclusions and recommendations.

In any case, both statements need to be re-examined if there is to be a balanced debate about the Treaty.

First, the context of the Treaty needs to be considered.

Why was one deemed necessary?

Some scholars believe that it was solely to protect Māori from the depredations of British settlers by establishing a system of law and order to govern them. There were around 2000 settlers, mostly in Northland. Māori population throughout New Zealand was about 120,000.

The request for this protection came from some Northland rangatira and from missionaries who forecast more direct conflict between settlers and Māori, but who also wanted the British Protestant ethic formally established in New Zealand and protected against incursions by French Roman Catholicism.

They had powerful backers in London, such as their own Church Missionary Society and the Aborigines Protection Society, which were at the height of their influence on government.

Other writers agree that although protection of Māori was a prime objective, other issues were in play. Principally that the British government had a responsibility to protect law-abiding settlers by establishing a form of countrywide government, especially since the New Zealand Company was planning several settlements.

Another consideration was that the Australian region, which included New Zealand, was seen as a British sphere of influence, trade and settlement that should be protected against the interests of other colonising nations, such as France.

This coincided with the missionaries’ aims. Before Captain William Hobson sailed for New Zealand with Treaty intentions, the Colonial Office would have been aware of developing plans for a French settlement in the South Island.

By the end of 1837, prime minister Lord Melbourne had already come to the conclusion that: "If we really are in that situation we must do something ... it is only another proof of the fatal necessity by which a nation that once begins to colonise is led step by step over the whole globe."

Reluctantly, the Colonial Office began planning to make New Zealand a Crown Colony.

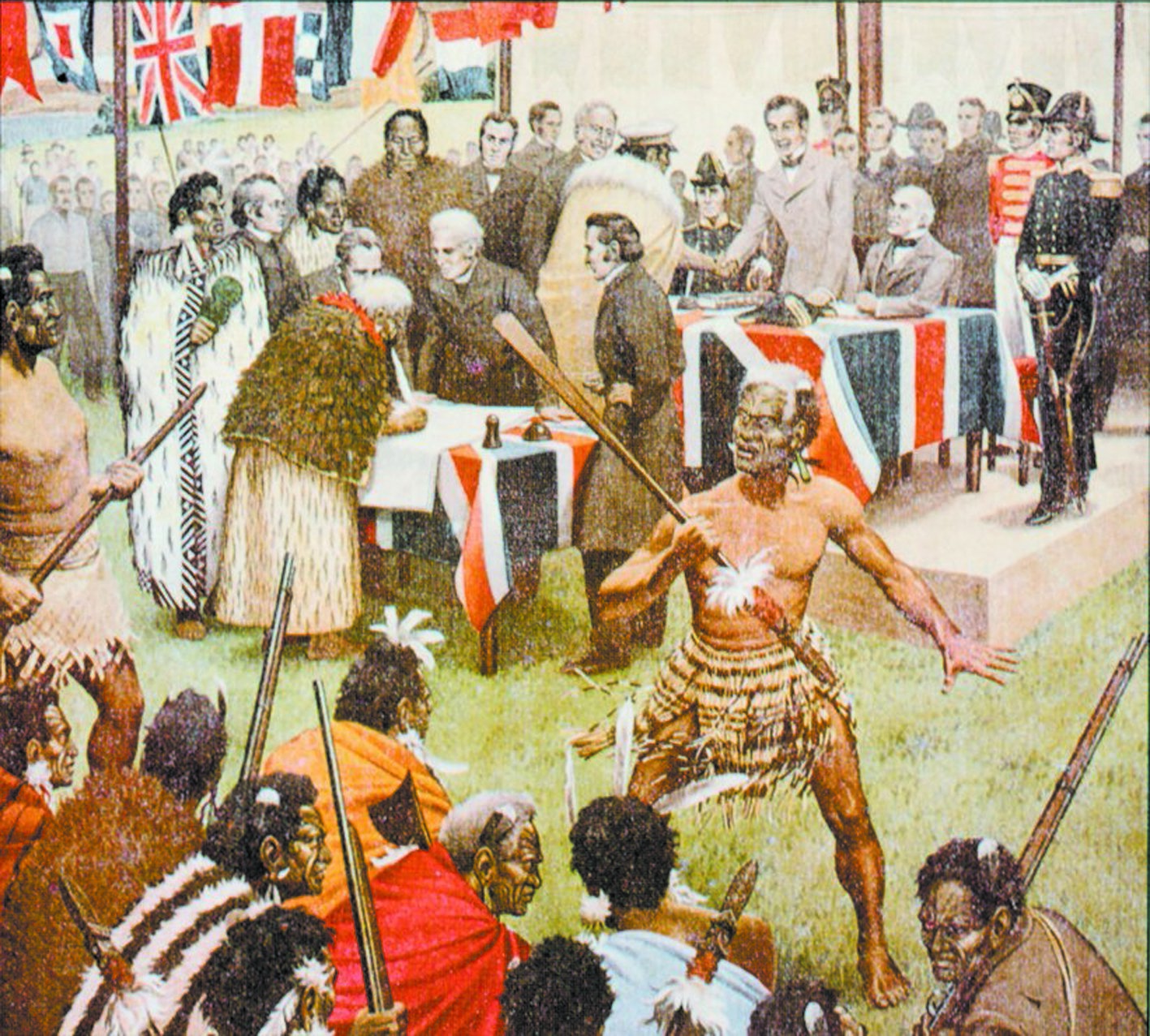

The English draft was then translated into Māori by Williams, his son Edward and Busby and read to chiefs at Waitangi on February 5, 1840. Much explanation and debate ensued with some chiefs opposed to signing, others in favour.

At one point, missionary printer William Colenso, fluent in Māori, asked Hobson whether he really thought the chiefs understood what was being proposed. The newly declared lieutenant-governor replied testily it was not his fault if they did not.

There has been argument subsequently that Māori did not understand what becoming a British Crown Colony would entail. Yet many chiefs had travelled to the colony of New South Wales and even to England and had a good grasp of the British colonial world.

On February 6, 1840, the assembled chiefs at Waitangi signed the Treaty, believing on balance that it represented a good deal.

But none of them had input into its wording, were unable to read it, and relied on the accuracy of its reading and explanation by Hobson and Henry Williams in particular, and the oral discussion that followed.

There are no accurate accounts of readings and discussions that occurred at many other sites as the Treaty was taken around the country. Some chiefs, especially in the Bay of Plenty area, refused to sign.

The Waitangi Tribunal’s declaration that sovereignty was not ceded by Māori relies on a key pillar, the legal doctrine of contra proferentem. This is a contractual rule providing that, where a promise, agreement or term is ambiguous, the preferred meaning should be the one that works against the interests of the party who provided the wording.

This rule, therefore, underpins the tribunal’s statement that only the Māori version of the Treaty can be used. There is a counter argument that contra proferentem applies to written contracts only and does not apply to what, at the time of agreement, was essentially an oral one.

What did the British government believe and understand had occurred at Waitangi? There was no deviation in their expectation and intention to make New Zealand a Crown Colony. Before February 6, 1840, Britain acknowledged Māori rangatira held sovereignty, although in a fragmented and disordered manner.

The object of a Treaty was to acquire that sovereignty, acting in good faith, and with the acceptance and understanding of rangatira.

The belief that Māori never ceded sovereignty rests on interpretation of Article Two of the Treaty.

Did the British government intend Māori to retain sovereignty in "partnership" or co-governance with the Crown? This seems highly unlikely, because such terms were not used at the time and are tribunal and judicial constructs of the past 30-odd years.

The British intention of Article Two was to treat rangatira as the equivalent of British aristocracy, entitled to retain ownership of their lands and possessions and the governance of their own people.

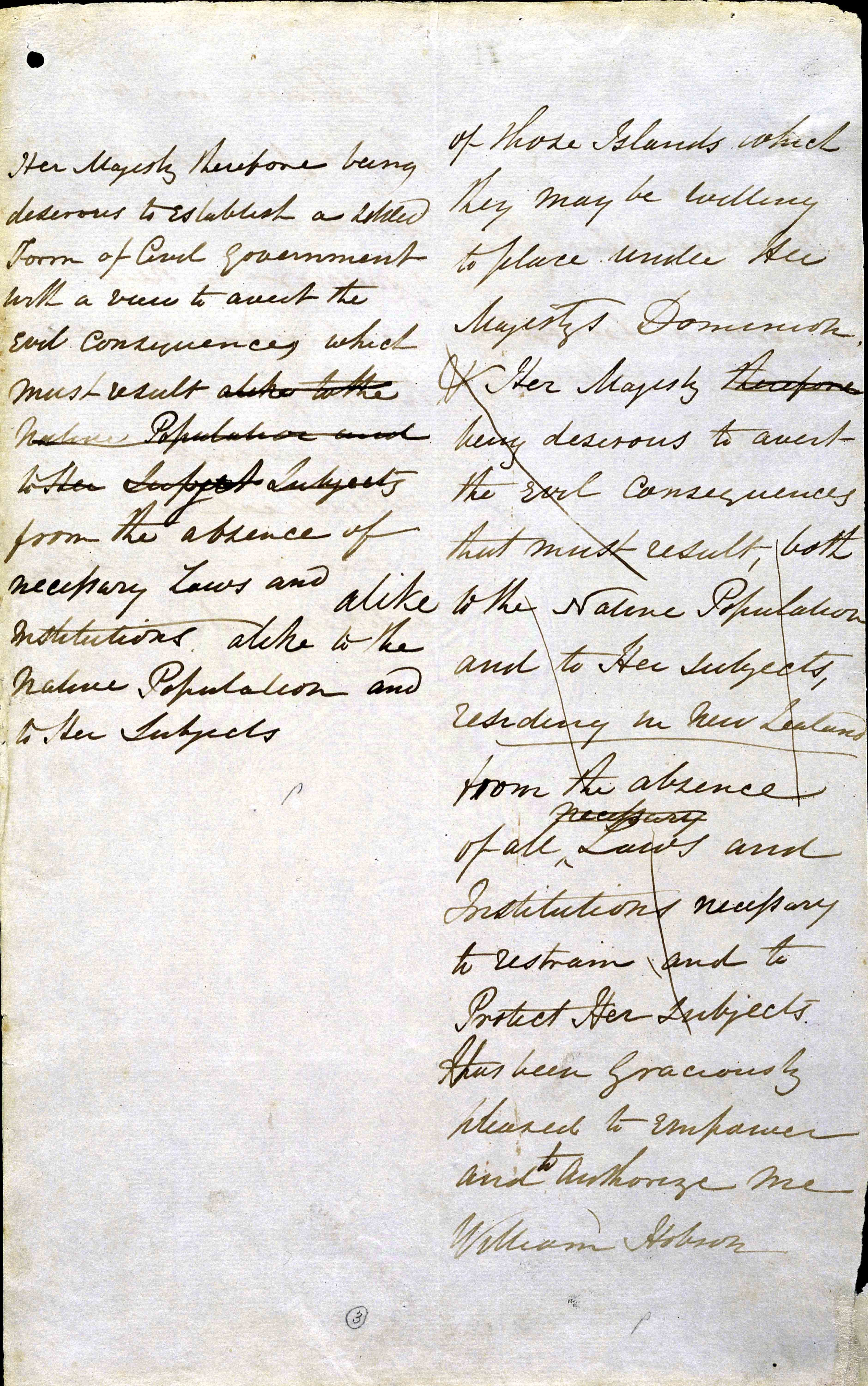

A clear indication that the Colonial Office intended a rule of law for everyone in New Zealand may be found in this extract from its instructions to Hobson. Māori welfare would "be best promoted by the surrender to Her Majesty of a right now so precarious, and little more than nominal [sovereignty], and persuaded that the benefits of British protection and of laws administered by

British Judges would far more than compensate for the sacrifice by the natives of a national independence which they are no longer able to maintain ..."

Further, "The establishment of schools for the education of the aborigines in the elements of literature will be another object of your solicitude; and until they can be brought within the pale of civilised life, and trained to the adoption of its habits, they must be carefully defended in the observance of their own customs, so far as these are compatible with the universal maxims of humanity and morals. But the savage practices of human sacrifice and cannibalism must be promptly and decisively interdicted; such atrocities, under whatever plea of religion they may take place, are not to be tolerated in any part of the dominions of the British Crown."

The belief that Māori signatories to the Treaty did not understand the concept of national sovereignty is questionable, even condescending.

But even this one use of the term "dominions of the British Crown" makes British intentions and understandings absolutely clear.

- Philip Temple is a Dunedin award-winning author and historian.