Guthrie-Smith describes in some detail visits to several "mutton bird islands" in Foveaux Strait and noted immediately how rats had devastated birdlife there. His muttonbirds were, of course, tītī or sooty shearwater, which once bred in vast numbers on these southern islands. Even today, the numbers that breed on the Snares, 100km south of Rakiura/Stewart Island, are in the millions.

In fact, despite an apparent population decline over the past 30 years, this species is still one of the world’s most abundant seabirds. There are populations in Chile, the Falkland Islands and southeastern Australia, as well as all around Aotearoa New Zealand, from Manawatawhi Three Kings Islands in the north, to Campbell Island in the south.

Tītī are long-distance migrants, our birds returning from the North Pacific to their southern breeding grounds in the early spring. At this time of year, an observer looking out to sea from the Otago coast can witness one of the world’s greatest migratory spectacles: a seemingly endless stream of birds heading south, with their characteristic wheeling flight and dagger-like wings, flashing glimpses of silvery underwing from otherwise dark bodies. Counting these adult birds soon leads to very big, almost unbelievable numbers.

Tītī were and are special taonga for Māori. Each year thousands of tītī chicks are harvested by Rakiura Māori on several southern islands. Northern iwi also harvest tītī, but this is a different seabird, a rather distantly related species of petrel. Surprisingly, there was once a similar tradition in Europe: 400 years ago, preserved chicks of the related Manx shearwater were considered a delicacy in the British Isles.

Targeting chicks rather than adults has allowed this harvest to be sustainable, since many chicks do not survive to adulthood anyway. Harvesting the long-lived adults would quickly lead to a decline in population and likely eventual extinction.

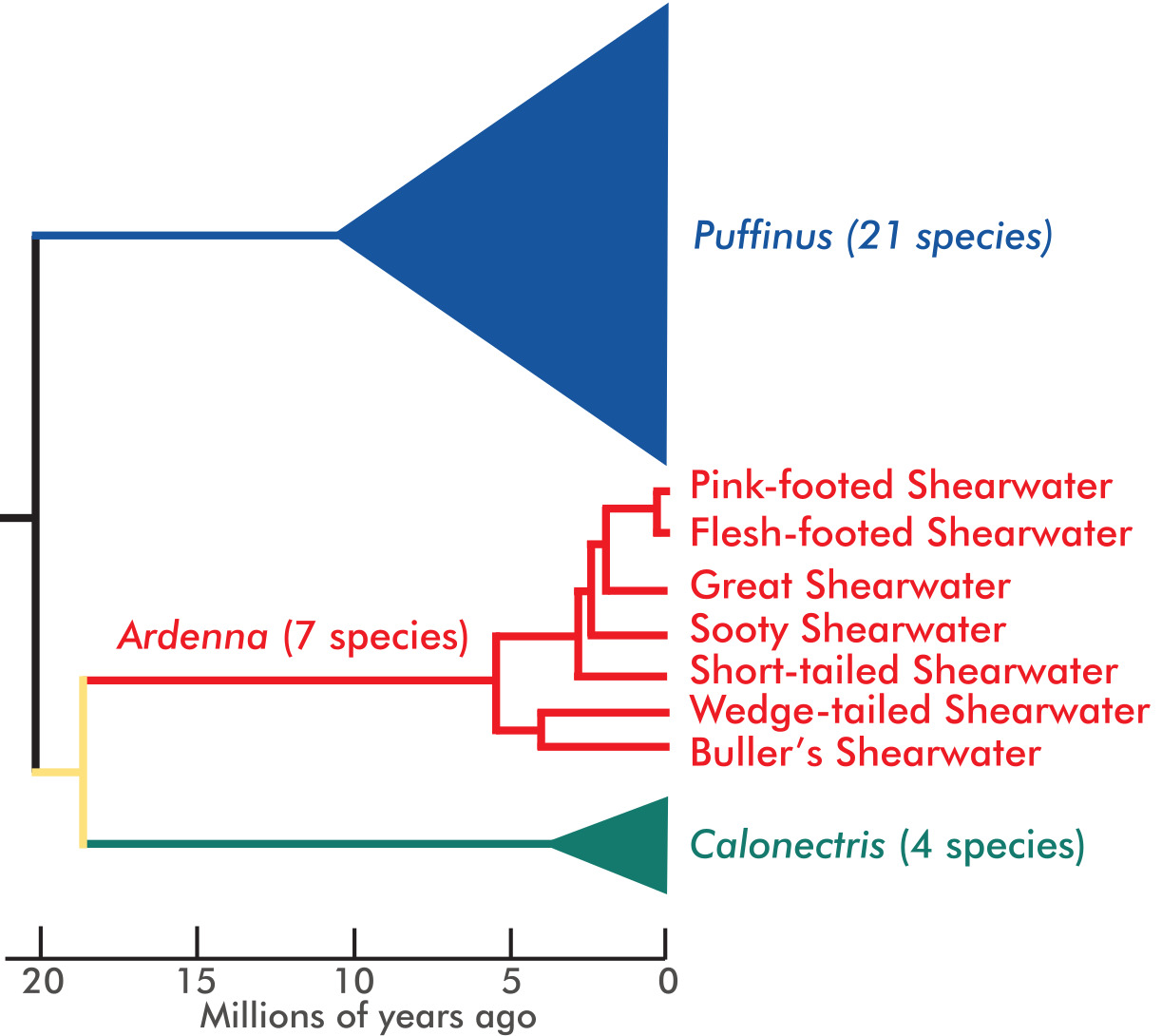

Puffinus now applies just to the smallest species and Calonectris to four of the largest species. The sooty shearwater fits into a group of seven medium-sized birds, in the genus Ardenna, and so its name is now Ardenna grisea.

This renaming, annoying though it is, even to scientists, illustrates an important aspect of biological classification: all the species in one genus should be each other’s closest relatives. Just as with people, names help us to identify close relations.

We can see from the shearwater evolutionary tree that the most recent ancestor of all the Ardenna species lived just over five million years ago. Since then, the group has diversified remarkably rapidly. The progenitors of our tītī separated from the ancestor of the great, pink-footed and flesh-footed shearwaters a mere two and a-half million years ago, just the blink of an eye on an evolutionary time scale.

Tītī still nest at Pukekura Taiaroa Head, one of the last breeding sites on the South Island mainland. Visitors looking for the albatross will not see any breeding titī, however. They arrive after dark and depart again before dawn to forage for food at sea.

Intensive predator control on Otago Peninsula means that rats, stoats and cats are largely absent from the colony, and it probably has over a thousand pairs breeding. So those of you who have traps out are not just helping penguins, albatrosses, geckos and skinks; you are part of the reason tītī taonga still flourish in our southern city.

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the department of zoology at the University of Otago