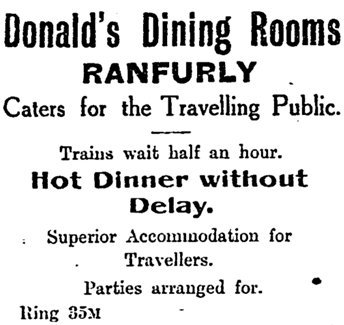

That’s why I was chuffed to receive from Peter Grant some stories about Charles Donald who was a butcher and private hotel owner in Ranfurly in the 1920s.

Charles’ nephew George Sutherland wrote of his experiences as a young man helping out at the butchery and I hope you enjoy this brief extract:

"Charlie’s sausages made from a secret recipe were famous. He had his slaughterhouse across the railway line and all his beasts and pigs were kept nearby.

Old Jake Forsyth took all the slops from the boarding house out to the piggery in an old spring cart. Jake was completely deaf and he was killed by a train at the Ranfurly station while crossing the railway line.

Dan Weir was the stock inspector and I had to keep a look-out for his arrival on horseback and warn Uncle Charlie so that if any uncooked offal was being fed to the pigs we had time to grab all the entrails and put them in the copper so that when the Dan arrived all offal was being boiled according to hydatids regulations.

I once did the slops disposal in an old Model T Ford and took off one day with two full slops drums but had to stop suddenly for a stray dog. The greasy, flyblown slops shot forward all over me much to the amusement of the locals drinking outside Massetti’s hotel.

Alex said, ‘Drive round the block, lad’. We went only 200 yards and the smell was too much. Alex yelled out, ‘Turn around quick', and so, at the age of 15, I became a licensed car driver.

Keeping meat was a problem. Flies were swatted away and maggots flicked on to the sawdust floor by a butcher’s knife. Some maggots were missed and I remember old Bill Blakely slamming down some of Charlie’s famous sausages, saying angrily, ‘Look at those maggots, Charlie — I’m off to deal with Bill Pringle.’

Bill Pringle was the opposition butcher.

Charlie retorted, ‘You do that, Bill. His bloody maggots are bigger and fatter.’

We dreaded serving pickled pork, especially in winter. We had to plunge our arms into a huge pickle barrel full of icy, salty water and the customer always wanted the roll of pork from the very bottom of the barrel.

Charlie’s wife Margaret, known as Cissy, always selected the meat for the boarding house and chose only the very best. She brought her purse and paid cash even though she and Charlie owned the shop.

Out the back of the shop was a red brick outhouse which housed the petrol-driven mincer. Great care was needed when feeding in the meat.

Charlie had a wooden plunger made to force the hunks of meat down the revolving mincer blade, but one day used his hand to press the meat down and nearly lost his arm when the blades just touched his fingers.

He stopped the engine, rushed into the shop and gave us a lecture on what not to do. From then on, the wooden block was always used.

When a circus hit town about 1927 Charlie was asked by the advance booking agent to have top-grade beef, freshly killed, to feed the lions.

A farmer called George told Charlie, ‘I’ve got an old horse. He’s bloody had it. What about knocking him off, picking off all the hair and selling him to the circus people as prime beef?’

‘Good idea, George’, Charlie said and the old horse was bowled over, cut up, cleaned of all traces of horse, and hung in the slaughterhouse to await the lions. I was there when the circus owner, an old hag of a woman with her purse slung over her arm, took one look at the red, scraggy-looking lumps of meat, and let out a scream of rage.

‘That’s bloody horsemeat. I will not pay for that.’

‘Take it or leave it', Charlie said. She had to take it, otherwise the hungry lions would have broken out of their cages and cleaned up all the cockies in Maniototo!"

The lesson from all this?

When old timers tell yarns — record them or write them down!

— Jim Sullivan is a Patearoa writer.