However, one of the people Dad knew was in a different category. Joan Robb was associate professor of zoology at the University of Auckland and an authority on reptiles. Conversations with her were exciting and informative, filled with humour. Indeed, she bears some responsibility for me becoming a zoologist.

Prof Robb’s book, New Zealand Amphibians and Reptiles, was published in 1980. In it she discussed all 21 of the species of skink from Aotearoa New Zealand that were known at the time. Today, after a new species from Southland was described last year, there are some 53 named native skink species, but the Department of Conservation records at least 78 species in total, with new discoveries still being made.

Two things have led to this increase in recognised skink biodiversity, more than a tripling of the number of known species in less than 50 years. The first is the diligent fieldwork of intrepid scientists, exploring wild and remote parts of the country. These scientists have discovered numerous populations, often very small, of many new species.

The second factor is the use of genetic tools to discriminate among species that look rather similar, but really are different. Members of the same species share the same (or very similar) genes because they interbreed. However, individuals of different species, do not. Consequently, their genes will be distinctly different from each other, and we can now measure this genetic distance fairly easily.

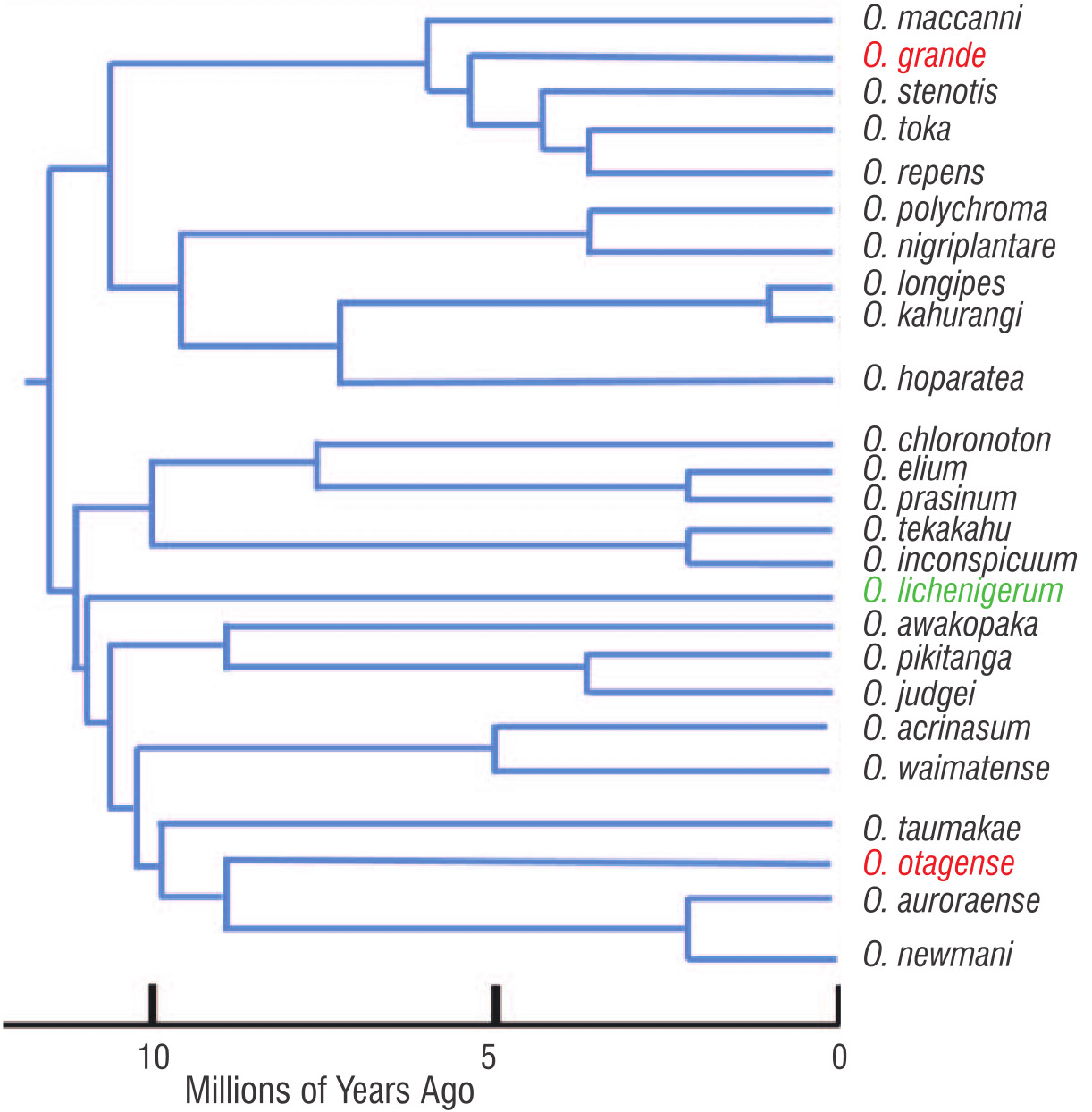

The same genes that are used to separate species can also be used to discover how different species are related to each other. More closely related species will have smaller differences between their genes; more distantly related species will be further apart genetically. Part of the evolutionary tree of our skinks, estimated from such genetic data, is shown in the diagram. Just 25 of the species are shown, fewer than half those named. Of the 25, just eight were known back in 1980.

Here in Otago, we have two distinct species that were once considered to be mere variations of the same species. In Robb’s book, she listed the Otago skink, Oligosoma otagense, and the grand skink, O. grande, as subspecies, geographically separated varieties of the same species, although she did express her doubts.

As the photos show, they do look rather similar. However, genetics has revealed they are not even closely related. Indeed, as you can see from the evolutionary tree, these two species last shared a common ancestor over 11 million years ago.

You can see the Otago skink when you visit Orokonui Ecosanctuary. On a sunny day, several can be easily spotted basking on slabs of schist in one of the protected enclosures. However, this species was probably never found in the Dunedin area. Rather, it is restricted to inland Otago, where it lives in and around rocky tors, especially those surrounded by dense tussock and native shrubs.

They are among our largest species. The standard way to measure lizard size is "snout-vent length" or SVL, the distance from the tip of the snout to the combined genital and excretory vent at the base of the tail. This measure ignores the tail itself, which some species can shed easily when threatened (and then re-grow it). The grand skink can reach a SVL of 115mm. The Otago skink is even larger, with a SVL of up to 140mm. If we included the tail, these numbers would more than double!

Sadly, both species, known as mokomoko to Ngāi Tahu, are endangered. These uniquely Otago elements of our nation’s fauna are bedevilled by the twin threats of habitat destruction and mammalian predation. Some places in Central Otago have been designated as reserves in an effort to preserve the vegetation and food sources — insects and fruits — these skinks require.

But these efforts are not enough. We need also to remove introduced predators — the usual suite of cats, mustelids, rodents (including mice) and hedgehogs — and then keep them out using special predator-proof fences. The good news is that if we do so, population numbers can recover, as has been found at the Mokomoko Drylands Sanctuary just outside Alexandra.

This twin-pronged conservation success is a first for our lizards on the mainland, but this approach needs to be expanded to more populations (and, of course, many of the other species). Given the elegant beauty of these mokomoko, which live nowhere else in the world, isn’t that what we should be doing?

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago