First elected to Parliament as the Liberal MP for Caversham in 1901, in 1909 — by when he had transferred to the new seat of Dunedin South — he put forward a private member’s Bill which urged that New Zealand adopt what we know today as daylight saving.

Parliament voted the Bill down, but this did nothing to deter Mr Sidey — he put the Bill back before the House in 1910, 1911, 1912 and every subsequent year until the House finally surrendered and approved the initiative in 1927.

Mr Sidey was not one to be deterred by little things such as distance and military bureaucracy when he ran headlong into both in 1915.

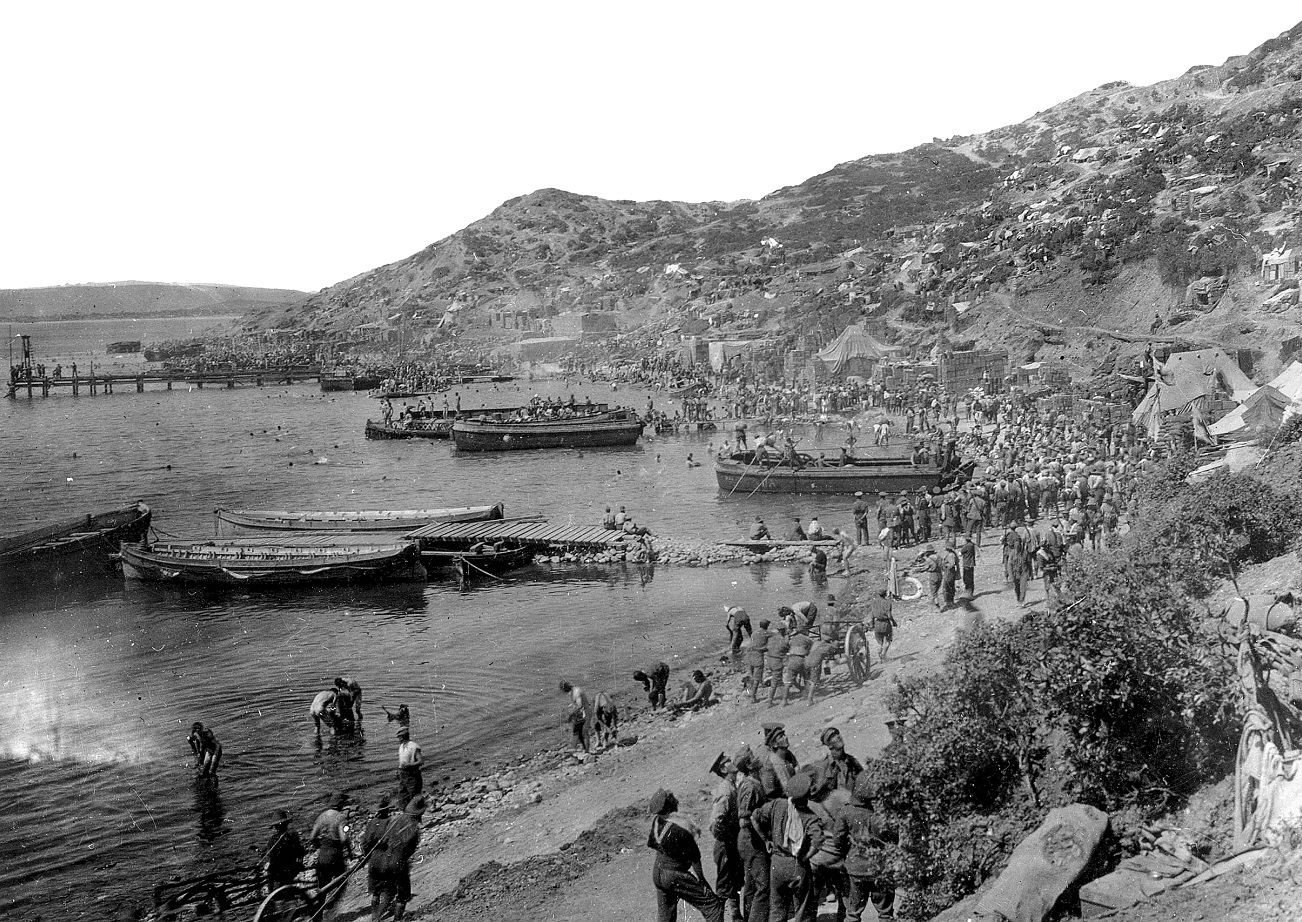

Like most New Zealanders, he had taken a keen interest in the onset of the Great War and the commissioning of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. On April 25, 1915, the NZEF had its first taste of action, the disastrous Dardenelles campaign, in which thousands were killed for little discernable gain.

Soon after the landings, Mr Sidey became preoccupied with an unusual constituency issue — had a soldier formerly of Waipori been the first New Zealander killed at Gallipoli?

Most would have assumed that a soldier of the NZEF would have claimed the "honour", but the New Zealanders did not land on the Turkish beaches until the afternoon on the 25th.

But then, as now, many New Zealanders had moved to Australia, and one of them was Wilfred Victor Knight.

The son of Frederick William Knight and Mary Snell Knight, nee Lean, Wilfred was born in Lawrence in 1890. After stints at primary schools in Waipori and Lawrence he attended Otago Boys’ High School before coming home to work as a storeman.

However, Waipori could not contain his adventurous spirit and in 1911 Wilfred moved to Australia where he embarked on a peripatetic lifestyle which included stints on a sheep farm, in the mines and driving trams.

When war broke out, Wilfred Knight wasted little time enlisting.

As a Dominion, Australia, like New Zealand, had been automatically considered to be at war when Britain declared war on Germany on August 5, 1914, local time. Private Knight joined the First Infantry Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force just 17 days later.

In mid-October, he and his comrades were shipped out to the Middle East, to train in Egypt. The following March he met up with his brother Eric, who had enlisted in the Otago Mounted Rifles, for what proved to be a final family reunion in Cairo.

Eric, a grocer before enlistment, was wounded in August 1915 and spent the rest of the war in the Middle East before returning home in 1919 nursing a dental cyst. He died in 1977. Wilfred, however, had a far less fortunate time of it.

He was not in the first wave of Australia soldiers who landed at dawn, but came ashore with the Main Force, of which Pte Knight’s First Battalion was in the front.

At this point, accounts differ. There is no doubt that Pte Knight was shot in the early minutes of the fighting, but questions remain as to whether those wounds were immediately fatal or not.

On May 3, Frederick Knight "expressed himself as only a true patriot could" when telling the Otago Daily Times that it might be the lot of any parent to lose a child defending the safety of the Empire.

Modern consensus seems to be that Pte Knight was evacuated to a hospital ship, where he died from his wounds between 24 and 48 hours later, and was buried at sea.

However, in 1915 the story soon began to be circulated that Pte Knight had been the first New Zealander killed at Gallipoli and Thomas Sidey set about trying to prove it. Mr Sidey’s correspondence file, held at the Hocken Library, contains letters he received about Pte Knight rather than those he sent, but contemporary newspaper reports say the MP’s interest in the case had "for some time engaged his attention".

Quite why, other than the constituency connection remains unclear, but it is quite possible Mr Sidey, an ardent imperialist, and Frederick Knight — a JP, the deputy coroner, a postmaster and an Oddfellow — might have known each other.

In July 1916, the parliamentary correspondent for the Star reported that after numerous inquiries, including with Australian defence authorities, it had been established "beyond doubt" that the facts of Pte Knight’s death had been established "beyond dispute".

Key to the MP’s certainty may have been a letter forwarded to him by Frederick Knight later that month, written to him by G. Slade, who knew a Pte McCormack, who knew Wilfred.

"McCormack told me that he saw Wilfred lying about 8am on the morning of the landings, about 50 yards from water’s edge. Wilfred was lying partly on his right side apparently unconscious, but still alive.

"McCormack did not have a chance to speak to him as he himself was charging the enemy an0d dare not stop, but he explained he did not think Wilfred would have been able to speak. He passed quite close to Wilfred and was quite sure it was him.

"He said Wilfred was wounded at a place now called Anzac and was buried in Shrapnel Gully."

From such slender threads legends are woven.

Wilfred Knight is remembered on memorials at the Lone Pine Cemetery, Gallipoli, the Lawrence war memorial, the Anzac Chapel in St Matthew's Anglican Church, and on the Otago Boys' High School war memorial gate.

Thomas Sidey went on to become Sir Thomas Sidey and was attorney-general and minister of justice in the United government of 1928-31.

His son, Stuart, after serving in the Pacific in World War 2, failed in three attempts to follow in his father’s footsteps as an MP, but did serve as Dunedin mayor from 1959-65.