Back in 1135, King Henry I of England, youngest son of William the Conqueror, famously died of "a surfeit of lampreys". Generations of schoolchildren have puzzled over just what this phrase meant. Did he really eat too many eels?!

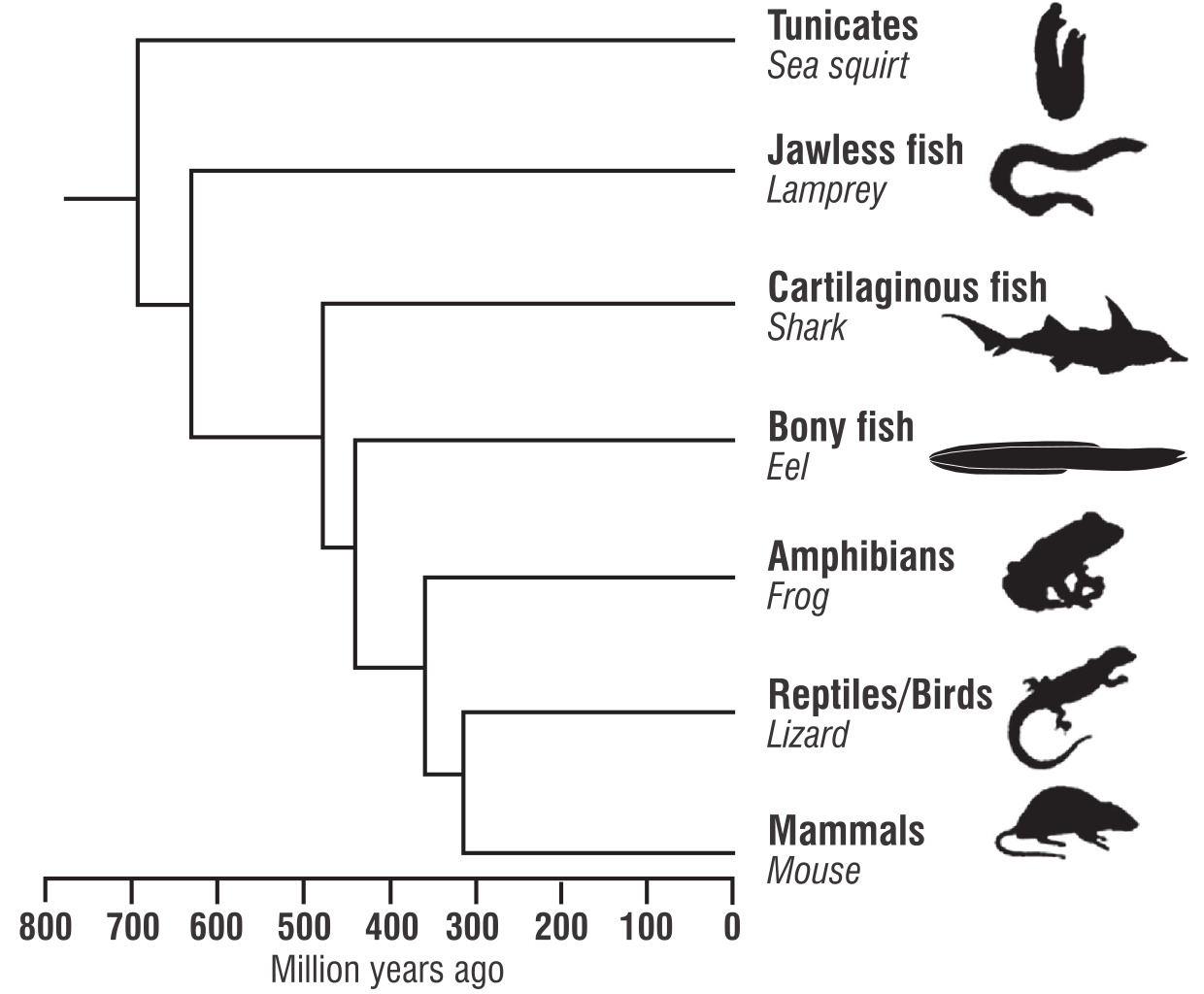

In short, no: it may well have been food poisoning rather than a fishy excess that carried off the king. Moreover, lampreys may seem at first glance to look like eels, but they are as evolutionarily distant from eels as they are from us mammals (see the diagram of their evolutionary tree below).

Lampreys have been on their own separate journey through time for more than 500 million years; we and eels share an ancestor far more recently!

In fact, the more you look at them, the clearer it becomes that lampreys are a bit weird. They have no distinct stomach. They have no bones; like sharks and unlike eels, they have a cartilaginous skeleton. Living species have no scales, and no paired fins (just one or two on their back). Most distinctively, unlike almost all other vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish, including eels), lampreys have no jaw.

This last feature is the clue to their whole biology. Instead of a hinged mouth, adult lampreys have a funnel-shaped mouth, studded with sharp teeth, and a rasping tongue.

We have only one species in Aotearoa New Zealand: kanakana (piharau of northern iwi), the pouched lamprey, Geotria australis. It is found all around the motu, including Rekohu/Chatham Islands. The same species is found in Chile and southern Australia. The English name refers to the large baggy pouch that develops under the eyes of males that are preparing to breed.

Yes, lampreys do look odd! But they are an important source of food for some endangered species such as hoiho (yellow-eyed penguin), as well as some fisheries targets like rawaru (blue cod).

The kanakana life cycle is reminiscent of eels and some other native fish involving both freshwater and marine stages.

Breeding occurs in freshwater and the eggs apparently benefit from some parental care (physical protection and oxygenation). The larval stage of about four years takes place in freshwater. These young animals burrow into soft sediments and filter the water to collect tiny pieces of food. They then undergo a six-month transition to the adult form, during which the characteristic adult mouth develops, before migrating downstream to the sea. After another four or so years sucking fish blood at sea, adults move back to freshwater to spawn, swimming upstream at night.

In many parts of the world, especially Europe, lampreys are a valued food source, today even a delicacy. Some species need to be very carefully cleaned to remove the toxic mucus that covers their bodies.

Unfortunately, kanakana numbers have fallen to the point where the species is now threatened. We are not sure of the reasons for this decline, but it is thought that habitat loss and degradation, especially of lowland rivers and streams where lampreys breed, is key.

Experiments with artificial nesting sites that mimic the underside of boulders are ongoing, in the hope that the populations will increase. Whatever the case, we need to improve our water quality if we hope to keep our special freshwater animals.

Another possible threat is a recently discovered condition known as lamprey reddening syndrome, which looks like extensive red bruising. Again, we do not know the cause, or even if the syndrome itself kills the fish or whether it predisposes them to fatal infections.

And in case you are worried about being bitten by a vampire eel if you go wading in a stream at night, you are quite safe. The young are too small to bite you, and adult kanakana stop feeding when they return to freshwater.

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago.