Jane McCabe

Otago University Press

REVIEWED BY JESSIE NEILSON

Kalimpong is a mountain hamlet in the Himalayan foothills of West Bengal. It is near the borders of both Nepal and Bhutan, and is tea plantation land, near Assam and Darjeeling. The land is fertile, home to cactus, orchid, and rhododendron nurseries.

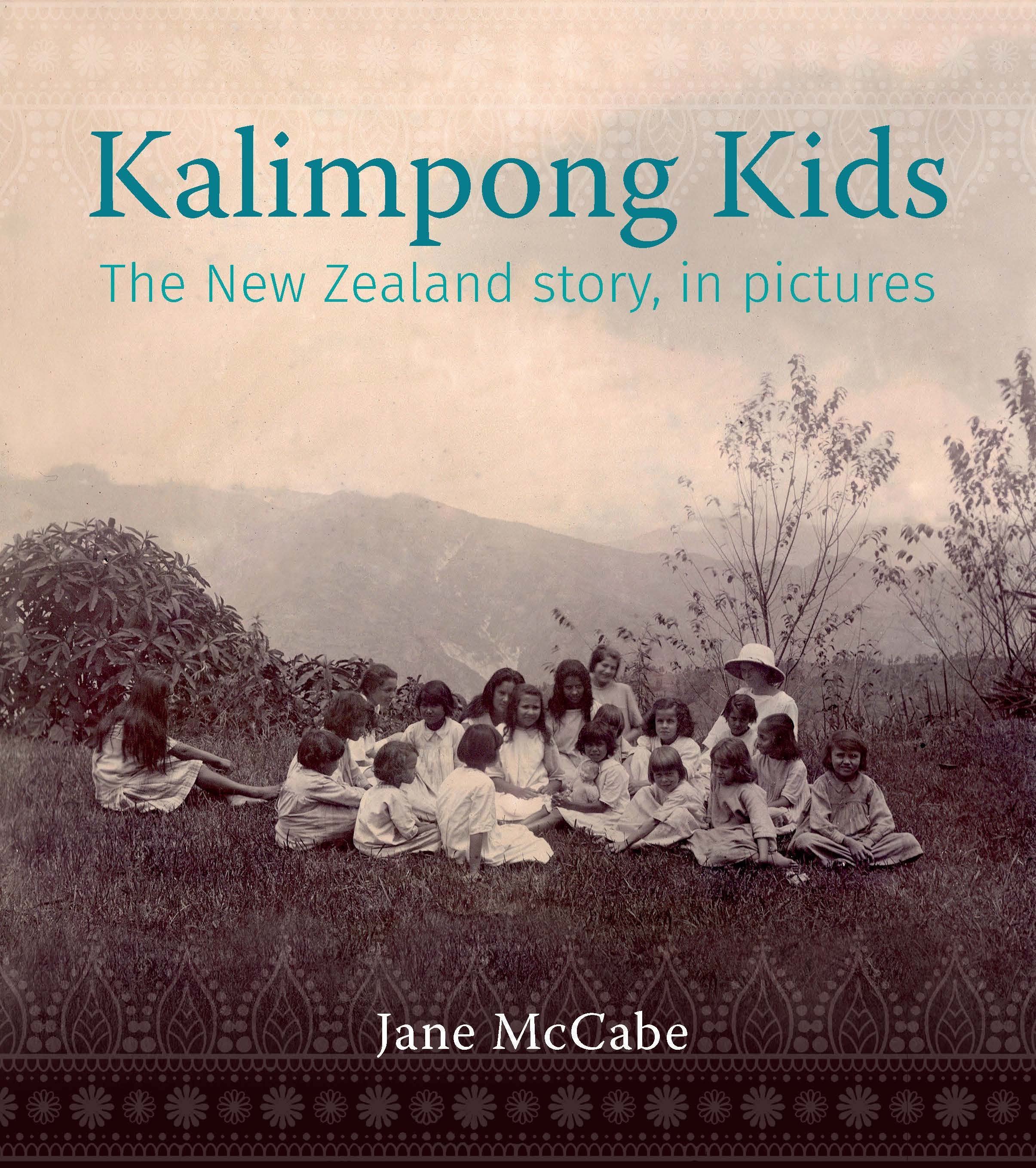

Kalimpong was a tiny British colonial outpost and hill station in British India. From the 1900s it was also the site of an educational initiative for the interracial children of British tea plantation managers and local women. Though these children were usually brought up in some comfort, they were also outsiders in British India and unlikely to be accepted by their paternal families in England. Therefore, this schooling system allowed another option. St Andrew's Colonial Homes, later to be renamed, grew into a sizable scheme, housing these young people in cottages with ‘‘House Mothers’’, while educating them in the British curriculum. On 250 hectares of grounds, it encompassed also a church, bakery, hospital, swimming pool, workshops and a working farm.

By the 1920s there were about 600 students, who were encouraged to immerse themselves in world affairs as well as in useful manual labour. The more promising would be sent abroad to begin new lives in colonial settlements, most never to return to India or know their maternal families. While diverse locations had been envisaged, in the end they made their way solely to New Zealand.

This ambitious scheme was the brainchild of the Rev Dr John Anderson Graham, a Presbyterian missionary from Scotland, influenced by Thomas Bernardo's scheme for sending British children to settler colonies. This initiative, though, involved the indiscretions of privileged British men.

Advertising for sponsorship of what became ‘‘Dr Graham’s Homes’’ emphasised opportunities abroad. New Zealand, considered egalitarian and open-minded, opened its doors to many of these graduates, and the first two male students arrived in Port Chalmers in 1908. Others followed to Presbyterian families around Dunedin, Waitahuna and Middlemarch, the men as farming apprentices and the women as domestic help, and later in clerical work. The scheme moved north, where Dr Graham continued to draw on his networks.

Author Jane McCabe previously worked in the University of Otago's history department and her reason for this beautiful photographic study is personal. McCabe's grandmother, Lorna Peters, was a Kalimpong kid, arriving in Dunedin in the 1920s.

Like the majority of these students, there was a huge reluctance to discuss their ‘‘shameful’’ origins abroad. Only since the 1980s have younger generations learned more through precious photographs and oral accounts, as well as by travelling to the homes, where every student was recorded meticulously in log books.

The grounds, cottages and educational system continues today, albeit in a changed form. Since independence in 1947 the language of instruction has been Bengali. The last of the tea planters left in the 1970s. Today the school caters to more than 1400 pupils of various backgrounds and ambitions.

This study is fascinating. With ample visuals of the people in their surrounds, of the pride and strength in their stances and expressions, it is an invaluable record.

Much is bittersweet in discovery: while some fathers kept in touch with their children, even eventually joining them, others were estranged. It was more difficult still for the mothers. While patriarchal connection was encouraged, it was the rare mother who was able to keep in touch with her child.

In Graham's defence, his achievements and pride in the trajectories of these young people are hugely admirable, and his attitudes ahead of his time. From his visit to New Zealand in 1937, friendships between the graduates were nurtured. Gatherings and celebrations burgeon here today.

Hopefully, the legacy of Kalimpong, and the connections between the various generations both here and in India will only grow as more stories are, piece by quiet piece, brought to light.

Jessie Neilson is a University of Otago library assistant.