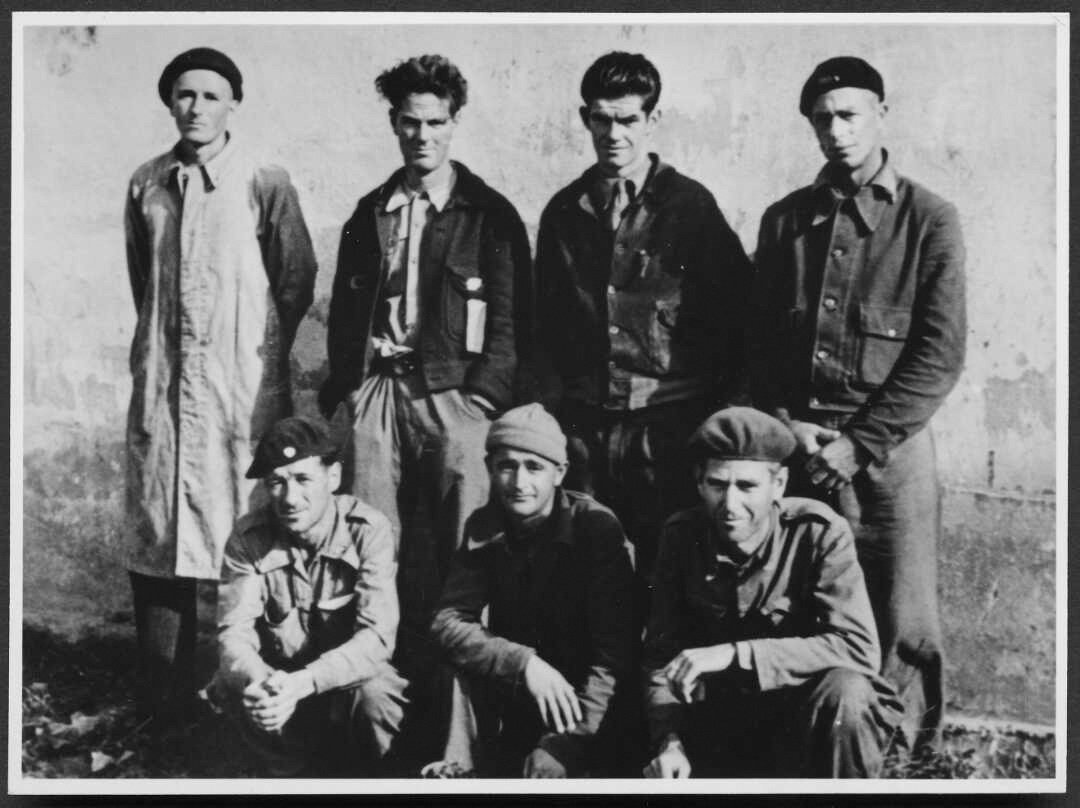

The photograph was probably taken in the town of Ripoli, close to the French border at the foot of the Catalan Pyrenees, circa October-November 1938. Photograph printed from a negative held by the Archive of the International Brigades, Moscow.

While writing about the groundbreaking Cromwell-born battlefield surgeon Doug Jolly for a new book, historian Mark Derby came across the extraordinary tale of Dunedin-born William Macdonald -bank robber, commando and diplomat.

On a night in September 1942, three trucks painted the yellow-brown of Rommel’s Afrika Korps nosed towards the heavily guarded entrance of the Axis-held port of Tobruk, on the North African coast. Their drivers wore Afrika Korps uniforms and spoke fluent German, but they were Allied special forces on an audacious mission to disrupt the port’s supplies of petrol, ammunition, weapons and food.

In the rear of each truck sat silent rows of men posing as Allied prisoners of war. Most were members of the highly trained Special Air Service (SAS), their weapons concealed under blankets. One of them, 29-year-old William Macdonald, was a Dunedin man who had spent time as a real prisoner in his own country. In this desperate raid on an enemy fortress, he hoped to outrun his unfortunate past and prove himself a hero.

Macdonald was born into comfortable circumstances in 1913, as the son of a lecturer at Otago Medical School and his wife, a nurse. Before the age of 2, however, his parents left him in care to work with military medical services on the Western Front. He would not see them again for four years. In post-war Dunedin Mrs Macdonald was known for her charity work with the hospital board, the Girl Guides, the Junior Red Cross and the Plunket Society. During the Depression she ran a relief depot, and received an OBE for establishing the Waikouaiti children’s health camp.

William was educated at Otago Boys’ High, served in its cadet corps, and sometimes boarded at the school when his mother was especially busy with charitable works. In 1933 the family moved to Wellington, where his parents intended him to become a lawyer. William had other hopes. He yearned to become a pilot, and began working as an unpaid mechanic at a Masterton aerodrome in return for flying lessons.

He dreamed of joining the Australian air circus led by barnstorming flyer Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith, but overseas travel required more money than the small allowance his parents provided. He carried out a string of petty burglaries and thefts before deciding on a more sensational crime. At that time pilots often carried revolvers as signalling devices, and this is probably how Macdonald acquired one.

On a quiet morning in August 1933 he walked into the Union Bank of Australia in Palmerston North’s Square, with the muzzle of a gun just visible beneath a raincoat over his arm. He handed teller William Loudon a note -"I have you covered. If you attempt to give the alarm I will shoot you. I’m desperate. Don’t hesitate" -and demanded £200 (about $30,000 in today’s money.)

It was sheer bad luck that he picked an intrepid teller. Loudon dropped below the counter, seized his own standard-issue revolver and fired several shots, one of them shattering the glass panel above the bank’s front door as the would-be robber dashed outside. It was likewise unlucky that Macdonald had spent the previous evening playing table tennis with another teller at the bank, who quickly identified him to police. Within minutes he was in handcuffs, still carrying his loaded weapon in his pocket.

His lawyer could offer only a plea in mitigation. Macdonald "had always been highly-strung and somewhat reckless in spirit", the court was told, and this temperament led him into "his theatrical and hopeless action in the bank". The judge was unmoved, and imposed a sentence of four years in borstal. Macdonald served two and a-half, then left for Europe, never to return.

For this adventurous misfit, the civil war that erupted in Spain in mid-1936 offered an opportunity to finally reach the skies. Spain’s left-wing government faced a military coup backed by troops from Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. In response, anti-fascist volunteers from many nations arrived to support the embattled government. Among them was New Zealander Eric Griffiths, who became a pilot with Spain’s Republican Air Force. Macdonald, however, was judged "too immature" for the air force, and was sent instead to the International Brigade base for basic infantry training.

He joined the mainly-American Abraham Lincoln Battalion and met another New Zealander there, former University of Otago student Arnold Maclure. They were soon flung into the blood-soaked Battle of Jarama.

"This is essentially a machine-gun war," he wrote to his mother, "and here we were faced with one of the heaviest barrages of machine-gun fire that has ever been put up."

During one patrol a machine-gun bullet ploughed into his right shoulder. In hospital he was treated by Cromwell-born surgeon Doug Jolly and Auckland nurse Una Wilson, and later given leave in Madrid to recover. There the flamboyant US writer Ernest Hemingway offered him a bath in his hotel room, "and served me a drink there while I was soaking". The heavy bombing raids on the city were less enjoyable. "I helped to pick up wounded women and dead children who at 11 o'clock on a bright sunny morning went out to their shopping, and their deaths. It was a relief to get back to the trenches."

"I hope you tell anyone who asks where I am," he concluded, "that I am in the Spanish Government Army, fighting fascism."

The 25-year-old Macdonald transferred to a transport section, hauling tanks of water both for drinking and to cool the machine- guns. In an interview published in this newspaper in December 1938, he revealed that this role proved little safer than trench warfare. An artillery shell struck the back of his truck, although its full tanks cushioned the force of the explosion. Throughout all major battles of the civil war, eventually with the rank of sergeant, Macdonald continued to drive trucks, sometimes loaded with munitions. He was repatriated along with all other foreign volunteers in October 1938.

This hardened and courageous soldier showed no inclination to return to New Zealand. In London he drove an ambulance and at the outbreak of World War 2 joined a New Zealand anti-tank battery as a gunner, marking his enlistment form "No convictions". He was sent to Maadi camp in Egypt, and in late 1941 transferred to the British Army and volunteered for parachute training.

Macdonald’s experience of frontline warfare, and his fitness and determination, gained him a place in one of the army’s most notorious and irregular units. From 1941 the men of the SAS -bearded, often shirtless and wearing Arab headgear -ranged for thousands of miles across the North African desert, raiding German and Italian airfields. The night attack on the Port of Tobruk was one of the riskiest. "We got into Tobruk all right, past the German sentries, and started to raise hell," Macdonald later recalled. "Blew up supply stores and set barracks afire."

His vastly outnumbered team of disguised desperadoes made it right through the huge military base to the coast, where they destroyed Italian gun emplacements in readiness for a sea attack by motor torpedo boats (MTBs.) In the darkness, Macdonald approached some barracks built into the cliffs above the port and dropped armed grenades down their ventilation shafts, killing all the unsuspecting Italians inside.

When the first small MTBs reached the shore, Second Lieutenant Macdonald ordered their crews and machine-guns on to high ground to defend his busy saboteurs. By now the entire port was alerted to the raid, and as the sun rose the SAS men were confined to a single building, where they spent the day under heavy fire. Their commander, Colonel Haselden, was shot down and Macdonald raced to pick up his body, but was blown off his feet by a grenade that killed his charismatic leader.

The raid proved a costly failure, as most of the planned sea and air support failed to arrive. "Half of our men never got back," Macdonald recalled. The other survivors split into small groups to try to escape under cover of darkness. Macdonald led one of these but was captured and spent the rest of the war in various prison camps, making repeated efforts to break out.

Fossoli camp in Italy held some 200 New Zealand soldiers and officers along with Britons and South Africans. Conditions were relatively pleasant, with sports teams and an excellent orchestra but Macdonald was not content to serve his time and wait for the armistice. After a failed escape attempt in 1943 he was sent to the punishment camp of Gavi, a 16th-century fortress known as "the Colditz of Italy".

A window of opportunity for escape appeared after Mussolini capitulated to the Allies and the Gavi inmates were transferred by train to Luckenwalde camp, south of Berlin. Travelling through Austria at night, Macdonald cut away a square of wood from the door of his carriage, released the catch and jumped out into the dark. He was wearing civilian clothing "but I spoke no German so I had trouble getting food. My worst trouble, though, was a psychological one. I got into a state of mind where I thought everybody on the street was looking for me ... it was this fear, rather than hunger, that made me give myself up." For this daring escape attempt he was later mentioned in dispatches.

"In Luckenwalde," he remembered, "I was always in trouble. Couldn’t keep my mouth shut." Again he was sent to punishment camps, first in the Czech Republic, then in Braunschweig, Germany. This last camp was no picnic. By 1945 its inmates were short of food, their clothing was inadequate, and their buildings were decrepit and poorly heated. Morale was at rock bottom when the camp was liberated by the US Ninth Army in April 1945.

Two years later Macdonald, now with a French wife, was back in North Africa, although this time, as he self-deprecatingly put it, as "a member of that vanishing species, the British foreign-service or colonial administration officer." Libya had been under British administration since its capture by Allied forces. Macdonald’s role as British District Commissioner of the province of Tripolitania was to assist the local people, mainly Arabs and Berbers, with the transition to full independence. He spent seven years dealing with periodic crises such as swarms of locusts, and administering land purchases for the US, British and French military bases nearby.

The saturnine young anti-fascist became an amiable, pipe-smoking representative of the Crown, and Macdonald finally achieved the respectability of which his parents might have approved. He was unable, however, to escape the trauma of his childhood and the strain of the war years. This troubled, haunted man, who had proved outstandingly brave and resourceful in warfare, died in Lisbon, Portugal in 1968, apparently by his own hand.