Children’s author Andy Griffiths has been blowing children’s minds now for decades.

Before his Writers and Readers visit to Dunedin next month, he tells Tom McKinlay about the happy confluence between a sense of mission and a flair for the absurd.

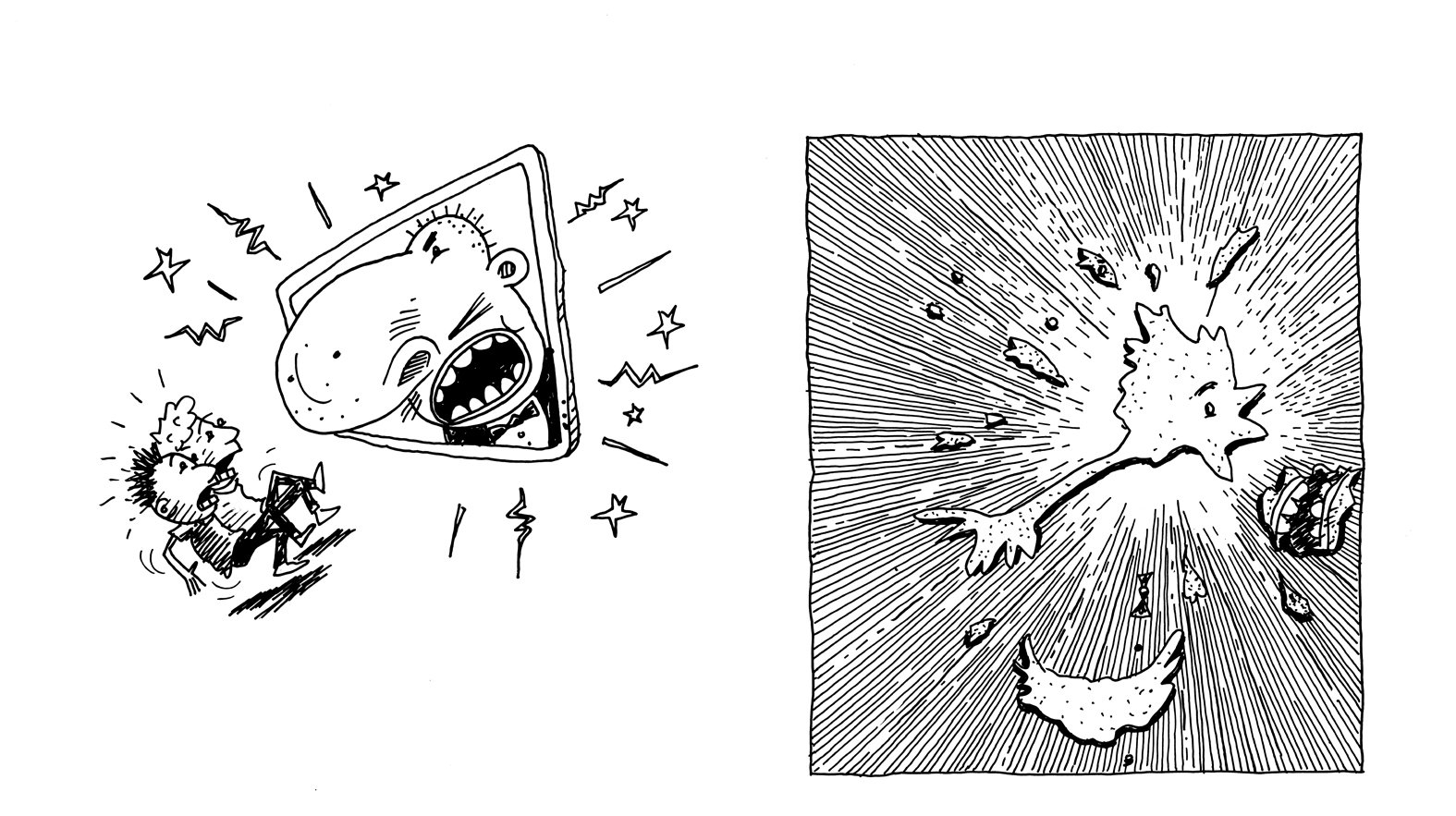

Away back in the first of the million-selling Treehouse books by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton, there's a picture of their publisher's head exploding.

We know him from the series as "Mr Big Nose''.

Under the picture the caption reads: "Above: An artist's impression of what it would look like if Mr Big Nose's nose exploded.''

The joke is, of course, that the illustration, by Denton, is the same as all the other illustrations in the book. They are all his - the artist's - impressions.

It's clever, maybe even too clever for some of the book's intended audience of primary school children.

But Griffiths still thinks it's funny. Reminded of the gag, there's a quiet chuckle down at the other end of the phone line.

The books, starting with the The 13-Storey Treehouse, all the way through to The 91-Storey Treehouse are full of such engaging crazy. There will be a story unfolding, but like a dinghy in the open sea, it will be buffeted from all sides by great tides of distracting comedy, only for the apparently unrelated elements of the maelstrom to be tied up and put happily to bed by the time you get to "the end''.

Take that first book in the series, The 13-Storey Treehouse. Griffiths' narrative is interrupted for chapter six, "The Barky The Barking Dog Show'', during the course of which a series of small frames, across several pages, show Barky the Barking Dog barking at all and anything until it disappears into a hole.

That survived the editor's pencil, but, says Griffiths, some of the madder digressions of early drafts do not.

"The first few drafts, it is just everything, the whole kitchen sink, every joke we can think of is thrown in,'' Griffiths explains of the creative process.

"And then as we come over subsequent passes we achieve a balance between diversion and between having a story where something is actually happening and the reader actually cares.''

In this, Griffiths and Denton have another, less-heralded collaborator.

"We have a crucial third member of the team, which is my wife, Jill, who is the editor,'' Griffiths says. "She has been the editor of every single book I have ever written. She sort of stands as the judge ... because Terry and I can get totally carried away with the diversions, to the point where she will sometimes say, 'look I think you are just amusing each other now, I think you have forgotten about the audience, you have forgotten about the plot and there is no tension anymore, there is no emotional drama going on, you just have a dog barking for 3000 pages. And we will go, 'yeah, but conceptually, that is really funny'.''

At which point, Jill, presumably takes up her pencil.

If that's an ingredient in their recipe for success, it's a good one. The Treehouse series is a phenomenon. Next month, the latest instalment will be launched, The 104-Storey Treehouse, the eighth in the series, each one having risen 13 storeys on the last. Each featuring the latest adventure of Andy and Terry (yes, it's them), two boys who live in a treehouse. Masses of fans, of primary school age and probably older, in dozens of countries, will swoop on a copy and do little else until it is read. Then wait more or less patiently for the next.

The books top best-seller lists. And they are not even Griffiths' first success. That stretches back to his Just series (Just Stupid, Just Crazy, Just Annoying etc), also illustrated by Denton, and the best-selling Bum books; The Day My Bum Went Psycho et al.

Griffiths is said to be Australia's most popular children's author, which if true, and it seems quite likely, is to a considerable degree down to the remarkable partnership with Denton. They have been working together now for quarter of a century; clearly having as much fun creating the books as their readers do reading them.

When they are working together, Griffiths says he often thinks it a very similar experience to just playing as an 8-year-old. Indeed, that feeling of rediscovered childhood was one of the inspirations for the Treehouse books.

"We just get lost in these imaginary worlds and the game of coming up with a plot. That is partly why I said, 'we should write about ourselves as living in a treehouse trying to write a book', because they are really complementary kinds of things.''

UNDERGIRDING that childlike sense of play, is a serious, but fabulously disguised, sense of purpose.

Griffiths, who misspent his youth fronting punk rock bands, eventually became a teacher and encountered the predictable classroom indifference to the written word.

"I started as a high school English teacher, and I'd come from being in punk rock bands. I was always performing, writing songs, putting on a show,'' he explains. "And I became a high school English teacher and I met a lot of kids who hated reading, were utterly disconnected from it. This is in the late '80s and there were serious discussions and debates about whether the book had reached its end and computer games and movies would take over.

"And I just thought, this is the wrong question to ask: you can have both. But the books hadn't really kept up with the pace of what was going on in those other mediums. I started to want to try to translate some of the energy that I get from rock 'n' roll and from alternative comedy, I wanted to go, 'let's put that into book form and bring the kids back to reading'. So that was central to my self-appointed mission, right from the beginning.''

Then Griffiths met Denton and immediately realised the artist had an "amazing ability'' to draw people into books visually, allowing him to "do what I can do with words''.

Books are a pleasure, he says, "an amazing experience'' that should not be tossed aside for other Johnny-come-lately media.

"The book demands a particular imaginative kind of exercise from the reader and it rewards enormously because it is so personal, because you are co-creating that world with the writer and I think we see that in the dedication and the love that we get from our readers who really own the series. Very few movies can do that, but books do it almost routinely.''

Griffiths and Denton will encounter that co-created world when they visit Dunedin next month, as part of an extensive tour to promote The 104-Storey Treehouse. Books such as theirs, as widely read as they are, become part of the culture.

There is for example, the catnary; part cat, part canary, invented early on in the series, and which went on to pull the airborne chariot for their near neighbour Jill (yes, she appears in the books too).

That particular flight of fancy, alongside a thousand others, now lives in the imagination of many.

"When I am overseas, all I have to do is go, 'oh, that Terry he's such an idiot','' Griffiths says, "and the kids go, 'oh, yeah, we know, we know, he put his underpants in the shark tank'. So there is instant familiarity: both Terry and I enjoy that.

"We love feeding nonsense into the imaginations of kids because we feel it is really helpful to help them grow, to expand and stretch and challenge them with absurdity. So it is very very satisfying.''

For all the lunacy, it is apparent that the twists and turns of the Treehouse tales are minutely plotted and carefully stitched together. Indeed, producing a Treehouse book stretches across most of a calendar.

"One book each year and that's about how long it takes to come up with a plot and integrate all of Terry's drawings,'' Griffiths explains. "And then we re-do the plots to fit his drawings and he re-does the drawings to fit the plot, and it goes backwards and forwards; a very detailed kind of process.''

Having sent the latest book off to the printer, the pair get a couple of months to catch their breath, plan the promotional tour and begin to think about the next one.

The mountain they have to climb to complete that next one gets 13 storeys higher every year.

"Yeah, I think we are getting more and more ambitious, and the books are certainly more complex at this point than they were,'' Griffiths says.

By the time they arrived at The 65-Storey Treehouse Andy and Terry were off time travelling.

"That's not something I thought we would be able to pull off, but Terry I think is obviously a genius and can seemingly rise to any challenge that I throw at him, no matter how bizarre. So the game going onwards for me is to keep throwing ever greater challenges at him to see if he can do it and I think he is just getting better and better.''

The pair have been working together so long, they now anticipate each other, he says.

"I can write now without him even being in the room and I know what he is capable of and I know what he will be able to do, so that allows me to write in a really free way ... because I don't have to describe it all, he saves me hundreds and hundreds of words of description, which makes the book so accessible to kids, too.''

Griffiths has previously revealed that he did not have a backyard treehouse himself, growing up, as there wasn't a suitable tree in the section, though he did spend some time in his cousin's.

However, he does credit some of his early reading as formative.

"My treehouse influence was really Enid Blyton's Faraway Tree series, which was all set in a tree.''

The Magic Faraway Tree books are now being developed as a live-action film by Neal Street Productions, the company behind the recent Paddington Bear films.

Griffiths describes the whole idea of being up in the branches as quite elemental.

"You can be up in that treehouse and see out, but nobody can see us. I think that maybe goes back to the time when our ancestors lived in trees and that was a safe place to be.''

That sense of safe harbour also separates the Treehouse books from the Just series, he says.

"The Just series is total chaos and anarchy and danger and the Treehouse has a lot of that, but it also has a safe place, which is the treehouse. I think that was the crucial thing that made the books really well loved by such a wide range of people. You have a place where you can take refuge from the madness and that's a very big difference between what we used to do; where we just unleashed the forces of anarchy and chaos and sat back and enjoyed the madness. Not everyone's idea of a good time, but a lot of people's.''

Eight books on in the series, there is little evidence of reader fatigue. Nor author, nor illustrator fatigue either.

"No, when we publish each book we listen carefully to what the audience is telling us, listening for any signs of fatigue or, 'when are you going to do something else?'. But the only question for the last eight years has been 'when is the next Treehouse book coming out? We are very happy to oblige them in that, because each book for us is a new book, because we have 13 different levels. We have to come up with those 13 levels and they suggest which way the plot goes, so it is the same but quite different in every book.

"We are willing captives to it, to the Treehouse juggernaut.''

We 'won the lottery', author says

Down the back of 30 Napier St, Dunedin there was once a stand of pine trees; perhaps eight. Maybe seven. They no longer stand.

And across those eight trees (or seven) was rigged a three-storey treehouse, constructed by my father, a man who otherwise exhibited no practical skills that anyone would recognise as such.

But we had the best treehouse in Mornington. Perhaps the lower South Island.

We climbed it, fell from it, played tag in it, spent a 40-hour famine in it, and I kissed a girl in it. The first time I had done that.

Involved in almost all these activities, even the last, was my neighbour and friend, Brian. He later became an artist. He was pretty good at drawing then.

So had we only turned our talents to it (I am assuming here we had sufficient), we might have beaten Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton to the publishing monster that is the Treehouse series.

I put this to Andy Griffiths.

He says he wakes up every day struck by the unlikely good fortune of his teaming up with Terry Denton and "being able to have a life of just creating pure nonsense''.

"So we kind of won the lottery.

"I often say that to young writers. To get a book published, you have won a lottery already. Then to get that book to actually sell and find an audience, that's like winning the lottery a second time. I think we have probably won it three times to have found collaborators as harmonious as we all are and an audience as dedicated. That is not something you can plan for.''

Authors such as Jeff Kinny, of The Wimpy Kid fame, and J.K. Rowling, of Harry Potter, who have had terrific success, all say you could not plan for it, Griffiths says. They did not see it coming, they were just doing something that amused them.

"That's totally out of your hands really, how it happens. The reward should be in the doing of the thing,'' he says.

"Really what we are doing is just this playful thing, that you can't demand a result from. You just have to play and then hope that someone else will enjoy it.''

Win a ticket

To go in the draw for a double pass to Andy Griffiths’ 104-Storey Treehouse show at the Regent Theatre, Dunedin, with Terry Denton, courtesy of the Dunedin Writers & Readers Festival, send your name, postal address and daytime phone number to playtime@odt.co.nz, with ‘‘Treehouse’’ in the subject line. Or mail to PO Box 517, Dunedin.