Mr Key believed that fast internet access held the power to lift New Zealand's economy up the OECD rankings and give entrepreneurs in a small country in the South Pacific an international competitive edge.

The previous Labour government had spent years tinkering and talking about what it would do but Mr Key appeared to take note of the discontent among IT circles and wanted to do something about it.

Communications and Information Technology Minister Steven Joyce was put in charge of the project and he told the Otago Daily Times he was happy with progress made.

All bidders had put their proposals to Crown Fibre Holdings, which was established to manage the Crown's investment in ultrafast broadband infrastructure over the next 10 years.

CFH had reviewed all the proposals and was looking for ways to make the tender process as attractive as possible, he said.

Several of the respondents to the Crown's initial invitation to participate said they supported a move to offering open access at layer 2 of the UFB as well as layer 1.

In particular, the service providers who would be purchasing UFB services and in turn selling them to consumers had said they supported such a move, Mr Joyce said.

Layer 1 services refers to dark fibre, or unused optical fibre, available for use. Layer 2 refers to the electronic data that can be sent along the fibre.

Mr Joyce said that making both layers open access would allow companies to differentiate different products to different customers. Allowing open access only on layer 1 meant companies offering the same products to all customers.

"Careful consideration has been given to the issue of open access. It is important that the open access model supports competitive outcomes and that it is suitable and attractive to the industry and private-sector investors."

One of the other concerns was that the bidding process covered a period of about 10 years. Companies were concerned that if they bid for 10 years, at a set price, the Commerce Commission might come after a short period and change the rules because new businesses will be competing against the existing copper network.

However, because the copper network would stay regulated, it was a "reasonably safe" assumption that the commission would not intervene.

The Government planned to have the UFB network meeting its first-stage commitments to the business, health and education sectors within six years and for everyone else within 10 years.

Mr Joyce had faced some criticism for the timetable but he said it was important to get the process right first time.

He likened it to building a road where a lot of thought and talk went into the planning before the road was built. Mr Joyce believed the deployment time would be a lot shorter than people expected.

The minister would not be drawn on the much-talked-about structural separation of Telecom where Chorus operations would be sold to separate Telecom's retailing and wholesaling divisions.

Telecom had indicated it wanted to be part of the UFB project, but some of the other bidders would also have to look at how they operated their businesses, he said. Telecom was the largest company and the most visible.

Mr Joyce had a warning for mayors and councils interested in becoming part of the UFB project. They needed to think carefully and make sure they were laying fibre for the right reasons.

Telecom's cabinetisation process was well under way, with about 84% of urban areas covered. The process was expected to be completed by the end of next year. That would lift urban areas up to modern broadband speeds and move New Zealand up the OECD broadband rankings.

The worrying issues were rural areas, half of which still relied on dial-up speeds. That was the reason for the Government's rural broadband project, he said.

New Zealand Computer Society chief executive Paul Matthews said one of the biggest decisions the Government had yet to make was whether to go with the Telecom-Chorus model or the "everyone else" approach for the UFB project.

There had been criticism about whether $1.5 billion was enough for the project but the Government appeared to want private equity partners to also put up significant investment.

Mr Matthews was in agreement with Mr Joyce that it was better not to rush the process.

"I would rather they allow plenty of time for it and do it once rather than racing in and finding out they have made a fundamental infrastructure mistake."

Although Chorus was rolling fibre out to regional areas, Mr Matthews was concerned there would be delays in supplying the necessary infrastructure materials.

It was possible to import what New Zealand did not make but now Australia was involved in the process, skilled workers could look across the Tasman for higher pay and Australia could secure most of the available materials for its broadband project, he said.

If New Zealand could keep its edge over Australia, the roll-out could come in well before earlier predictions.

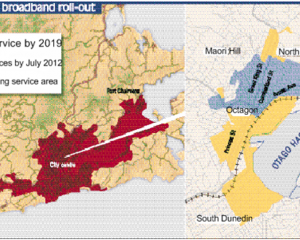

Asked about how UFB could be rolled out in Dunedin, Mr Matthews knew about the fibre already laid in the central city because he had owned and operated a business here.

Dunedin had a problem in that it was an older city where newer cities had been laying cable in preparation for ultra-fast broadband.

"Dunedin has to do a bit more to get it in place. That will be a challenge and it will depend on what technology ends up being used."

Major improvements, such as horizontal drilling and shallow trenching, had been developed overseas for laying fibre in built-up areas.

If companies laying fibre in Dunedin had access to that technology, the process could be sped up, he said.

"It could be technology solving a technology problem."

The Telecommunications Users Association generally supported the changes announced by Mr Joyce, chief executive Ernie Newman said.

"We believe the decision to require local fibre companies to offer open access services at both layer 1 and layer 2 is practical and commendable.

"The question of which layer will result in the more competitive downstream market has exercised the minds of many people in and around the industry for 18 months."

While users were naturally impatient to see the build started and get access to the new era of services, it was an inter-generational investment and it was important to get the basics right, he said. The Government was wise to take its time.