A recent thread I wrote on Twitter about the changes to Dunedin’s George Street retail precinct attracted several comments and reactions, some of which came at me via e mail rather than the public platform that Twitter so conveniently provides.

Some comments were supportive of my view, others were not. This article is an expansion of the points made and a more detailed exploration of the role of red brick in Dunedin.

My major criticism was the abandonment of the Dunedin inner-city standard red brick paver in the revamp, its promoters and designers having instead chosen to use grey stone and concrete. This major departure from the long established Dunedin red brick brand threatens to anonymize the centre city from distinctive heritage capital of New Zealand, to just any other city centre; an Anywhere.

The planned anonymising greyness of Dunedin’s centre city is symptomatic of many things in contemporary culture as Alex Murrell writes in his excellent essay The Age of Average, where he argues that “from film to fashion and architecture to advertising, creative fields have become dominated and defined by convention and cliché. Distinctiveness has died. In every field we look at, we find that everything looks the same”.

Murrell poses the question; Is soulless becoming the default design direction for urban architecture? and notes that the price of creative convergence is the shedding of identity in brands and products, urban environments and architecture.

Among the examples he shows there is a compelling image of twenty five makes of SUV currently available, all presented in the same colour. The makes are almost indistinguishable one from another because their side profiles are remarkably similar. He acknowledges the wind tunnel effect being a possible reason but suggests that they’re also designed to appeal to as wide an international market as possible; the use of predictive analytics to shape the model that the data indicates will sell best in a global market and that can be manufactured in the most efficient possible way.

In 1996 around 40% of cars sold were monochromatic (black, white silver or grey). Twenty years later that figure had increased to 80% according to Murrell - stark contrast to the multi-coloured array of vehicles many of us remember from preceding decades.

This phenomenon is also happening in colour choices of buildings; commercial buildings that were once painted in a vibrant range of colours are increasingly being repainted in shades of grey as their repaint comes up on the maintenance schedule.

Some people responding to my criticism of the greyness of the design of the George Street retail revamp have said I haven’t engaged in points made in the consultant’s report about aesthetic decisions that were made, and in particular the lack of colour.

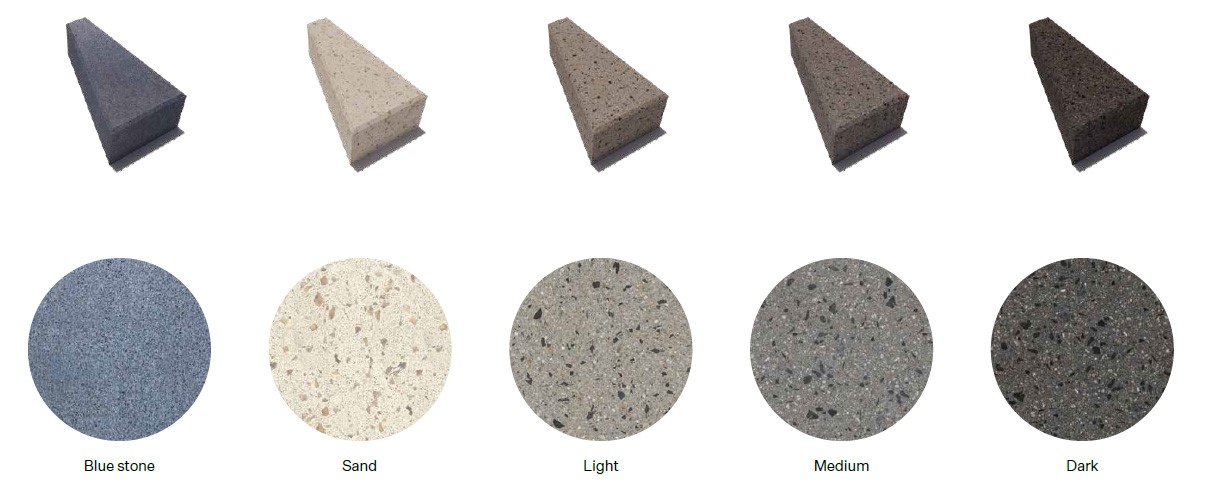

It’s not necessary to read a report to understand the lack of colour in the design, one need only walk along the street, however in fairness I’ll repeat what it says about the paving. There are five ‘colours’ which are described as; Blue stone (dark charcoal grey), Sand (beige), Light (light grey), Medium (medium grey), Dark (dark grey).

This grey revamp of George Street is the same greyness you see in Auckland, and the same greyness planned for the changes to Courtney Place/Manners Street in Wellington.

Even though it has been part of the Dunedin’s city paving for over forty years, red brick is completely absent and not discussed or referenced anywhere in the heritage section of the design consultants George Street Report..

Heritage – hidden in plain sight is a subheading in the Heritage section of the report which goes on to state that George Street “contains a richness of heritage buildings and building façade that are significant contributors to the character and sense of place of the Retail Quarter” ironically completely ignoring the material that those heritage buildings are made of – Red Brick. This is a shockingly shallow interpretation of heritage values of the place. Dunedin IS red brick!

This humble and often hidden little hero of our built environment has been around for thousands of years. In his Oxford Dictionary of Architecture, Professor James Stevens Curl devotes seven pages to ‘brick’, and gives fulsome explanations of its own fascinating terms and language developed through millennia of its ubiquitous use in buildings dating back 6,000 years ago in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and 4,600 years ago in cities of the Indus Valley in Pakistan. Various visiting scholars have reported that the bricks in those surviving buildings were as sound as the day they were made.

Negative comments I’ve noted about brick pavers have ranged from them being a trip-hazard, that they look dirty and old, they are not wheelchair-friendly, that it’s time to ‘move on’, and when voting to “ask staff to develop costed options” for the Octagon (ODT 21/6/2023), Cr Barker justified a vote to proceed with a comment that the Octagon looked “run down and sad”. If only Council voted funds to properly maintain what’s there - a fraction of the cost of the major overhaul seen in the new grey George Street.

And of course, Costed Options means engaging architects, planners, engineers, landscape architects, et cetera to advance design work and detailed cost estimates. Once on paper it will be near impossible to change, Council commitment will instead escalate and those making the decisions today, be they politicians or staff, will move on in the three-yearly cycle of discard & replace that is the hallmark of local government. In their wake will be left the flawed decision to throw out the brick in favour of the grey paver.

Red brick is the hidden in plain sight material of George Street and much of central Dunedin; a city with a richness of architectural diversity to satisfy anyone with even a passing interest in the built environment. It is an interesting and comfortable place perhaps best exemplified by The Octagon, the envy of many cities around New Zealand and centrepiece of Dunedin.

Typical of any traditional city plan it is the central gathering place to meet, grab a coffee and a slice at one of the many bars and cafes, where you can take in a movie or visit the Art Gallery, or check out the Town Hall under the clock tower.

All the while, you’d be walking on red brick paving, the energetic and colourful reminder and connector to Dunedin’s collective memory of what has gone before – its cultural heritage.

- Ian Butcher is a heritage architect based in Oamaru.