On Wednesday, Justice Williamson-Atkinson, 17, appeared in the High Court at New Plymouth where he was jailed for life with a minimum period of imprisonment of 11 years on charges of murder and burglary.

Williamson-Atkinson was asked if he had anything to say as to why a sentence should not be passed upon him according to the law.

"I didn’t do this," he told the court.

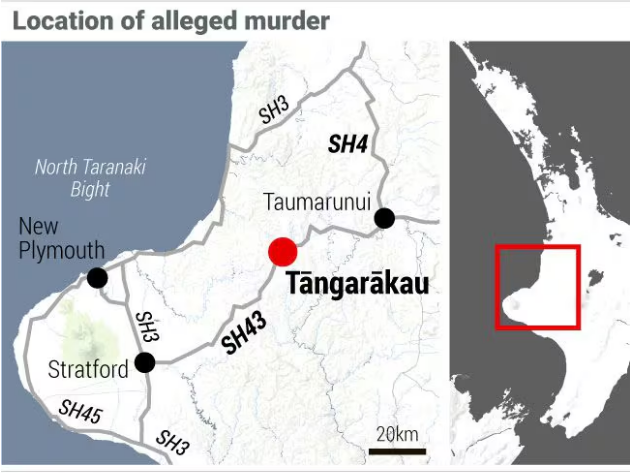

But at a trial in November, he was found guilty of murdering Humphreys, whose body was found at Bushlands Campground in Tāngarākau, eastern Taranaki, on May 7, 2022.

Williamson-Atkinson was on a programme for at-risk youth when he snuck into Humphreys’ camper to steal his car keys and then stabbed him five times.

At sentencing, defence lawyer Matthew Phelps argued a life term of imprisonment would manifestly unjust, but Crown prosecutor Cherie Clarke submitted the case did not reach the threshold to avoid such a sentence.

Phelps said Williamson-Atkinson was 15 at the time of the offending and has been diagnosed with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

He pointed out adolescents had less self-control, were more impulsive, less able to consider the impact of their behaviour, were more likely to engage in risky behavior and were more vulnerable to peer pressure.

"The offending and the behaviour, in my submission, is consistent with all of those factors."

Phelps submitted the court then had to factor in Williamson-Atkinson’s cognitive impairments, which he said further impacted his executive functioning.

"He has extreme difficulties with impulsivity, he tends to act in the moment, he has a reduced ability to understand and think about possible consequences."

Phelps argued that given Williamson-Atkinson’s youth and cognitive issues, a finite sentence with a minimum period of imprisonment of 50 per cent was appropriate.

But Clarke submitted that when there ws a heightened risk of public safety, which she said applied in the teen’s case, then a sentence of life imprisonment was rarely found to be manifestly unjust.

Clarke said Williamson-Atkinson had shown no remorse or insight into his offending.

She pointed out he had still not accepted responsibility for the murder, and had maintained that with his denial from the dock.

"And that maybe and is probably impacted by FASD but FASD can’t exclude that and it is therefore impact on his ability to rehabilitate."

Clarke submitted it was paramount to the protection of the community to impose a minimum period of imprisonment.

Justice Francis Cooke said the teen’s case was not an exceptional case where it was manifestly unjust to impose life imprisonment.

In sentencing him to life with a minimum period of imprisonment of 11 years, he encouraged him to make the most of his time behind bars.

"Eleven years may sound like a long time before you are considered for parole but it is important that you think about your future and you take advantage of all of the help you have in prison, and do things like completing NCEA qualifications.

"It is only by getting help and working on yourself that you can maximise the chances of you being released once the minimum period of imprisonment passes."

Burglary turns fatal

Williamson-Atkinson was staying at Bushlands Campground with Start Taranaki, a programme for troubled youths run in partnership with Oranga Tamariki, at the time of the murder.

The Hastings teen had taken a knife from the communal kitchen at the campground and snuck out of his tent during the night.

He wanted to leave the campground but needed a car so he broke into Humphreys’ camper to steal his keys and, during the burglary, repeatedly stabbed him.

The outdoor enthusiast was a former Royal Air Force serviceman from the United Kingdom.

At the time of his death, he lived in Rotorua where he worked at Southern Cross Healthcare as an anaesthetic technician.

He had stayed at Bushlands Campground only weeks before and was excited to be returning with the camper trailer he had just bought.

Within hours of his arrival, three Start Taranaki youth workers arrived at the camp with Williamson-Atkinson and two other teens.

The Kaponga-based organisation provides an eight-week programme to at-risk youth involving time spent in the bush, the beach, a marae, and in a residential space learning skills such as barbering.

Evidence was heard at trial that the youth workers generally slept in the same tents as the teens and removed knives from kitchens at any site the programme visited. But that did not happen on this trip.

Early the following morning, two of the youth workers discovered Humphreys’ body. He was lying face down on the ground, about 20 metres from his camper.

Williamson-Atkinson’s DNA was found around the cut holes in the sleeping bag Humphreys was in when he was stabbed, and Humphreys’ blood was found on the sleeve of the teen’s jersey.

Evidence was also heard that during a conversation with a relative, Williamson-Atkinson confessed to having "killed someone".

But at trial, defence lawyer Nicola Graham maintained it was another teen on the programme who had killed Humphreys.

Williamson-Atkinson had told police he had gone into the camper after the other teen stabbed Humphreys and took the knife away for him. He said the other teen had planned to steal Humphreys’ car keys.

There was no forensic evidence that linked the other teen, who has refused to provide police with a DNA sample and a statement, to the stabbing.

He has permanent name suppression and has not been charged in relation to Humphreys’ death.

- Tara Shaskey, Open Justice reporter