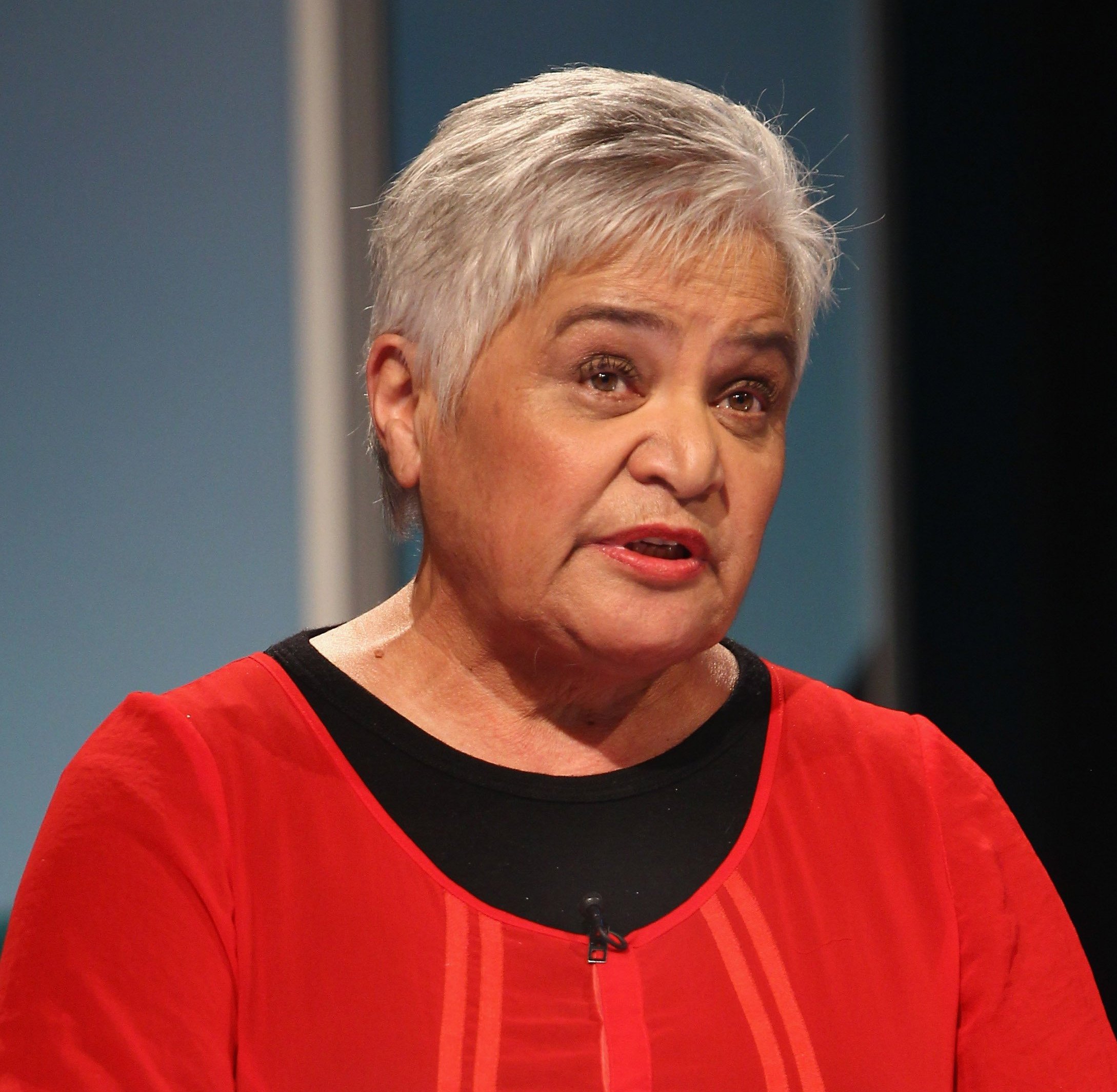

Forthright and dedicated, Tariana Turia was a politician who succeeded in doing what many would deem to be impossible.

Walking away from the Labour Party when a Cabinet rank might have beckoned, Turia achieved that rare feat of forming a new political party and then getting elected back to Parliament afterwards.

As if that was not enough, she took the fledgling Māori Party to where no-one thought it would go — into a governing arrangement with the National Party — and won policy gains which have endured to this day.

From being a pariah and alleged to be a dangerous separatist, she ended her life as Dame Tariana Turia, a respected figure right across the political spectrum.

Tariana Woon was born in 1944; her father was a United States serviceman (whom Turia never met) and her mother was Ngāti Apa, Ngā Rauru, Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Whanganui. She was raised in Putiki, a settlement near Whanganui, by a grandmother, whāngai (informal adoption) parents and aunts.

After attending Whanganui Girls’ College, Turia trained as a nurse: she retained a lifelong passion for health and health equity issues.

She combined that with a desire to improve the lot of Māori, and worked for Te Puni Kōkiri and various Māori health providers, including a stint as chief executive of Te Oranganui Iwi Health Authority. Despite not speaking te reo herself, Turia was also heavily involved in the kura kaupapa and kohanga reo movements and with her husband George Turia, whom she married in 1962, she led a marae-based skills and employment training programme for a decade.

The couple had four children, two whāngai children and were foster parents to several other children.

George Turia died in 2019: he and Tariana had more than 50 grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Turia had always had a lively interest in politics, but she was galvanised into public life by the 1995 protest occupation of Wanganui’s Moutoa Gardens.

A high-profile demonstration aimed at highlighting Māori claims relating to the river and adjacent land, Turia was a leading figure throughout: one of her sons was arrested for beheading a statue of former premier John Ballance.

After an unsuccessful bid to become a Whanganui district councillor, Turia — who had been approached several times before — agreed finally to become a Labour party list candidate.

Ranked at what looked a very electable 20th on the list for the 1996 election (the first MMP election), Turia only just scraped into Parliament due to Labour’s poor party vote share of 28%. Appointed Labour’s spokeswoman on Māori health and youth issues, Turia caused a stir on her first day by swearing her allegiance to the Treaty of Waitangi.

After Labour’s victory, she was made an associate health, housing, Māori affairs and social services minister outside Cabinet, but that status was jeopardised early on when a speech Turia made to a conference, in which she compared the colonisation of New Zealand to the Holocaust, was widely condemned.

After a stern dressing down, Turia apologised in the House for her comments.

The controversy may have cost Turia a shot at Cabinet: when Labour was re-elected she was made Minister for the Community and Voluntary Sector and retained most of her associate roles but was not promoted.

Turia had returned to Parliament in 2002 thanks to having won the Te Tau Hauāuru seat, but she resigned a year later in protest at Labour’s proposed law change to reverse a court ruling relating to Māori claims to the foreshore and seabed.

Turia stood in the by-election she had forced under the banner of the Māori Party, which had formed in the wake of her resignation, a contest which she won easily.

In the 2005 election, she was joined by three colleagues, including co-leader Pita Sharples (now Sir Pita), as one of the opposition parties.

In the 2008 election, the Māori Party returned five MPs. It was assumed that the Māori Party would remain in opposition, but new National prime minister John Key signed a confidence and supply agreement — which was not needed to ensure a majority — with it.

In return, Turia and Sharples were made ministers outside Cabinet — a status they retained when National maintained power in 2011 — and Turia was backed to create what was her lasting political achievement, Whānau Ora.

Poorly understood and somewhat controversial at the time, Whānau Ora aimed to channel government support for Māori through Māori providers pledged to address generational and systemic inequalities.

Turia was minister of Whānau Ora until 2014, when she retired from politics.

Despite the vicissitudes of politics, the portfolio and the policies initiated by Turia remain in place to this day.

Dame Tariana was made a Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit in the 2015 New Year Honours for services as a Member of Parliament.

Outside of Parliament, she remained a strong voice for Māori and lent her mana to a number of campaigns and causes.

Dame Tariana suffered a stroke early in the new year and died on January 3, aged 80. — Mike Houlahan, ODT files.