As Jack Hassell rested against a tree trunk after being left to die by fellow soldiers, his prospects of hearing from Queen Elizabeth II again were as remote as the Burmese jungle he languished in.

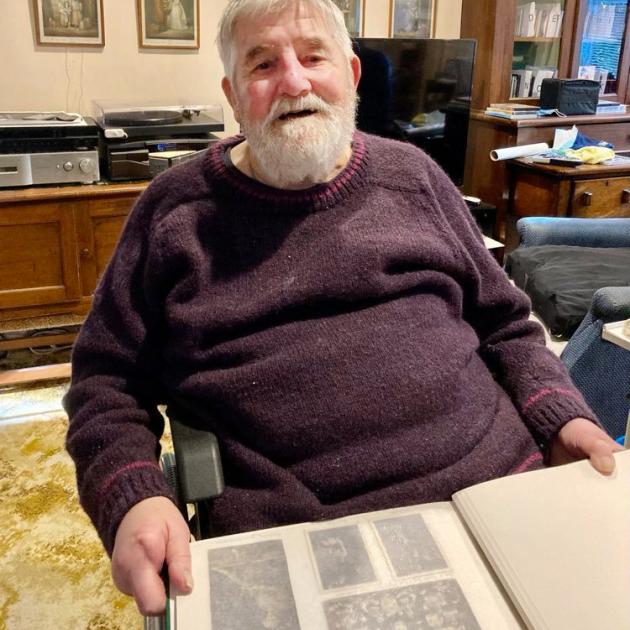

Yet in 10 days, all going well, the adopted Cantabrian will receive a message from Her Majesty to mark his 100th birthday.

Jack’s odds of surviving World War 2 looked grim when his Welch Regiment unit forged ahead without him after he succumbed to illness.

“This was a war walked on your feet. You marched everywhere and if you were taken ill, there were no hospitals and no way of getting you to a hospital,” Jack explained.

“They just had to abandon you. They propped you against a tree, left you a couple of big bottles of water, a bit of food, a rifle and some ammunition. ‘Bye bye Jack, best of luck’ that was it.”

Luckily, Jack recovered before the Japanese or tigers found him. He then used a compass to track down his mates.

“I kept thinking I had to get up and move. One morning, I don’t know how long I was there, I woke up and felt a bit better. Fortunately, I knew where they were going, you went by compass, there were no maps.

“It took me about three days to catch up with them. They’d stopped, I staggered in and one of the boys called out: ‘Jack’s here, for God’s sake’. They didn’t expect to see me again.”

“We got cut off by some Japanese, we were completely surrounded. They used to charge our perimeter at night, and they’d shell us during the day time. There was a stream, but it was full of our dead mules so we couldn’t drink the water.

“The shell burst a couple of feet away and blew his head off. One of my feet had shrapnel, I got off pretty well.”

Eventually the British were rescued by the Indian Rajput Regiment and the Gurkhas; Jack was ferried to a field hospital until the wound healed.

He returned to the front, if you could call it that, and also contracted hepatitis A. American medicine saved him from losing a foot, or worse, to gangrene, the consequence of perpetually wet feet.

“I was very fortunate, I was in a very good hospital in Assam (India) and I was one of the first people to get the new magic (cure). I forget what it’s called now, the Americans discovered it at the beginning of the war, but it was very scarce."

As he reflected on his longevity - British and Commonwealth nations suffered 71,224 casualties during the Burma campaign - Jack admitted luck outweighed good judgment.

“Every time I had anything bad there was something good to put it right, I was very lucky,” he said, before pondering those not so blessed.

“I’ve helped bury so many of my friends. I remember a young chap, he got a lump of shell case in his liver.

“He was obviously dying, his head was on my knee. I’ve never forgotten. He looked at me and said: ‘Jack, can you get my mummy?’ It’s heartbreaking it is, really.”

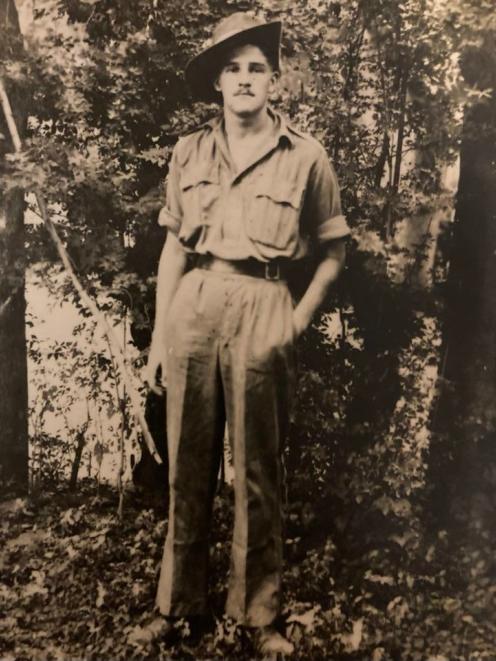

Born in Mau, a town in Uttar Pradesh regarded for its saree (traditional dress) industry, because dad Ray was stationed at a British army barracks there as a bombardier with the Royal Artillery, Jack was shipped back to Wales as a baby.

Once his mum Maude - in country as an officers’ ladies maid - learned a snake was found near his cot, Jack was headed for Cardiff where he was raised by a grandmother and an aunt.

However, he always had an affinity with his birth country, so welcomed a posting to India with the Welch Regiment, before crossing the border into what is now known as Myanmar.

“They drove the British all the way back through Burma right up to where you drop down into India,” he said.

“My regiment and a (Scottish) Highland regiment rushed there and we stopped the Japanese in their tracks.”

He then toiled in the Burmese jungle, in spite of having no formal preparation for that theatre of warfare.

“It was all-in fighting. It was all very close stuff, patrols. There were no bridges, no roads. If you wanted to cross a river you’d use a machete to cut some wood and make a raft. Lot’s of fun.”

Brewing tea, that quintessentially English pastime, was also no comparison to back in the UK.

“You cut through the bits of wood, get the matches, light a little fire, boil a kettle and make yourself a cup of tea. You had to get used to the idea that you’re not going to live long enough to drink it.

“As you’re raising the cup, the sniper could be in the tree taking aim. You get used to it, it becomes part of life really.”

Near the end of the war Jack was involved in the liberation of Mandalay.

“That was the Japanese last chance to halt our advance and they lost. After that they had to run for it.”

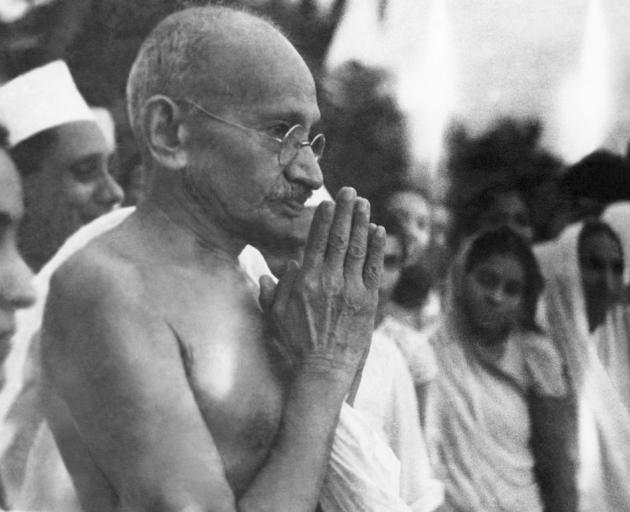

“I was always in favour of Indian independence. Sometimes Gandhi would have a big demonstration and one of the (army) servants would brown my face. I’d borrow their clothes and I used to go on protests,” he said.

“I looked the part, they did me up properly. There’d have been trouble if they found out, as a serving soldier, that was mutiny.”

It is no surprise Jack considers India home as, perhaps unusually for a Welshman, he never sang in a choir or worked down a pit and he doesn’t follow rugby.

Asked if he was at the Arms Park on December 19, 1953, the last time Wales beat New Zealand, the road cycling and squad enthusiast almost sheepishly revealed: “I didn’t know who the All Blacks were, I know that’s a dreadful thing to say (living here).”

Jack had hoped to return to India after the war and join its army but the physical and mental hardship he endured meant he was unfit for service.

“When I came out of the war I wasn’t all that brilliant,” said Jack, who had two sisters and a brother.

One sibling remains - Jack’s youngest sister Mavis lives in Wales.

“I was in about seven hospitals because I developed amnesia from the shock,” he said.

“That lasted quite some time. I’d be back in England, the war long over. I’d be on a bus and I’d suddenly get the idea I was going the wrong way, or it was going to be dangerous, and I’d get off miles away from where I was supposed to be.

“It (memory loss) vanished eventually. My memory came right, it took a while, three or four years.”

Thankfully he remembered the sweetheart he left behind when he went to war, Jean, who he met while they worked in a Cardiff department store.

It was her death that prompted Jack’s move to Christchurch in 1997, home to his daughter Sue.

“I was on duty outside the back door. It opened and the Queen came out with a couple of ladies in waiting and gentlemen.

“She stopped level with me and said: ‘You’re looking very smart, soldier’ and I said ‘Thank you, ma’am’ and that was it.”

Jack has needed a wheelchair for the last three months or so to aid his mobility due to arthritis, but otherwise he is in fine fettle apart from being a little unsteady on his feet.

“I was working in a factory (in Penarth, south of Cardiff), making dyes for plastics and there was a stoppage with the machine.

“I put my hand up the chute but I hadn’t stopped the engine, simple as that. There was a bump, I shook my hand out and said: ‘There should be another finger there, where’s that gone?’ It snapped it off.”

Jack had no particular theory for the age-old question for someone about to reach triple figures: ‘What’s the secret to your long life?’ He deferred to a medical expert.

“One of the heads at (Christchurch) hospital got interested in my case and he said: ‘I think you had such a rough do here, there and the other, I think your body has developed its own protection. I’ve done some calculating and I think you’re going to make 105'.”