As anyone who caught snapper as far south as Doubtful Sound would have surely told you, last summer was incredibly strange.

That was largely due to a freak marine heatwave that turned the Tasman Sea into a warm bath for a long time, fired a record-hot summer, melted ice caps and lured swarms of jellyfish to our shores.

What might this summer bring?

While the picture looks much more like the conditions we're used to, scientists say it'll still have some unusual quirks.

On the drier side

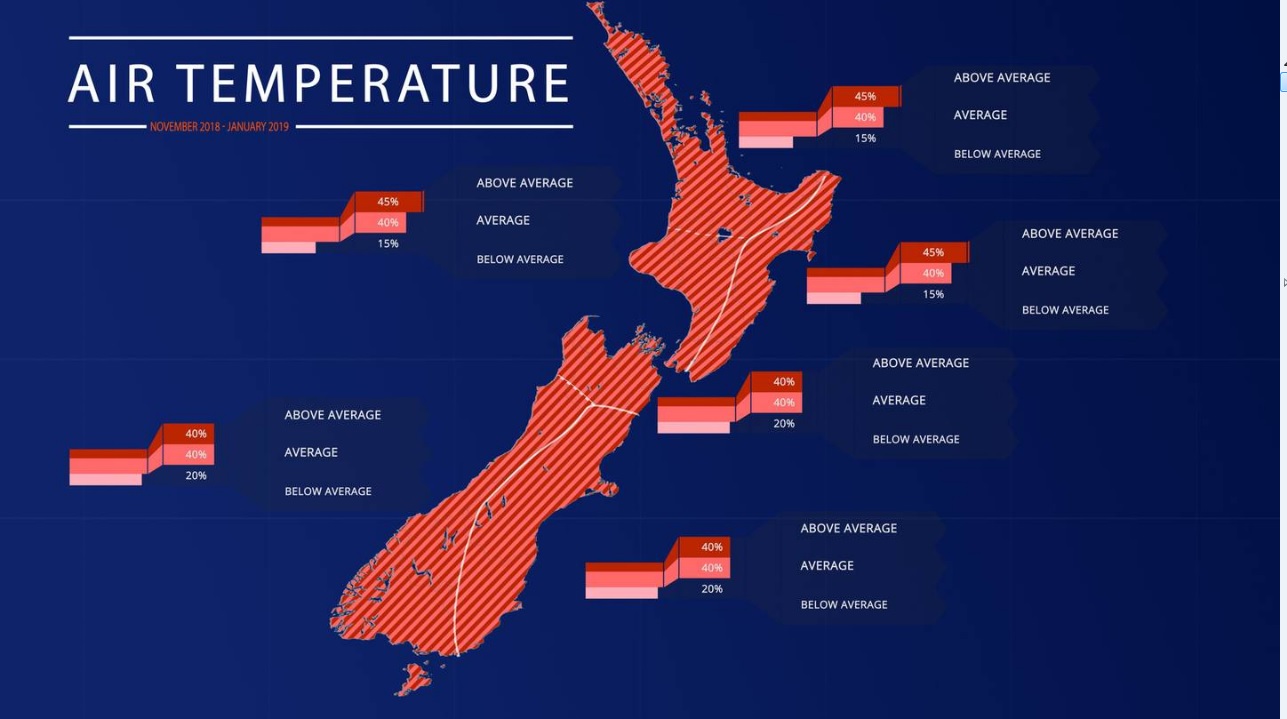

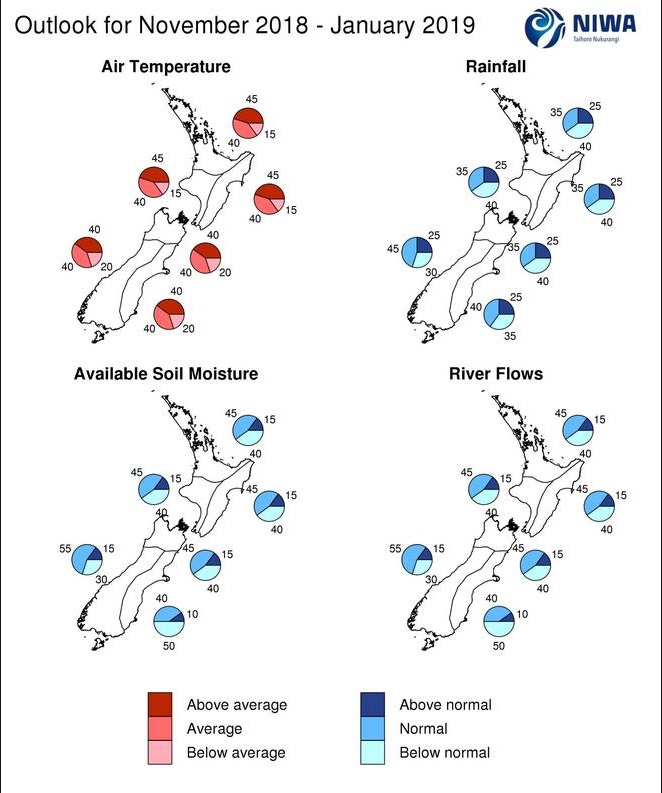

Across all regions, models showed an equal chance of temperatures being either near or above average through to the end of January.

"For New Zealand, while conditions are most likely to lean on the warmer and drier side of the spectrum, there is likely to be a bit more variety than last summer," Niwa meteorologist Ben Noll explained.

While last summer brought persistent northerly-quarter winds and much higher than normal pressure to start, the coming three months were likely to be more mixed in terms of wind flows and pressure set-ups.

But first, Niwa was predicting a more settled picture, with warmer-than-average air temperature and plenty of fine weather.

Drought hadn't hit anywhere yet, but Niwa was closely watching a handful of regions – the East Coast, Bay of Plenty, Auckland, Northland, Coromandel and the lower and western South Island – for the usual dryness.

It was also too early to pick winners and losers for the coming summer, Noll said, but he expected the tourism industry at least might benefit from extended tranquil spells.

"For farmers, I see the outlook as an opportunity to plan for what is expected."

"While it may still feel a bit cool when you jump in the water right now, seas are up to a degree above average along our coastlines," Noll said.

"That figure is most likely to increase during the coming month.

"It might be the case that at the start of December, our ocean temperatures are near where they would typically be during January."

But the surf would still be nowhere near as warm as it was in the lead-up to last summer.

Noll pointed out that many key ocean and atmospheric drivers worked in concert to produce last year's unprecedented marine heatwave.

Scientists have since said that combination would be considered unusual even decades from now, when climate change would have further warmed the world.

"While it doesn't necessarily look like we are headed for another marine heatwave, above average or much above average sea surface temperatures are not out of the question for the official start of summer next month."

In the background, scientists were observing the slow emergence of an El Nino climate system.

El Nino in the wings

New Zealand's climate is principally coloured by what's happening in the oceans and atmosphere surrounding us.

Over the past month, sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific have warmed notably, increasing from 0.25C warmer than normal in September to 0.75C above normal.

That was enough to signal that an El Nino would form between now and January – and scientists put the probability of this as high as 88 per cent.

This ocean-driven system typically brings cooler, wetter conditions, bringing higher rainfall to regions that are normally wet, and often drought to areas that are usually dry.

But the models indicated this El Nino – and its impact on us – wouldn't be quite like the usual type.

Another index covering the eastern Pacific, near South America, continued to show significant variability – leading scientists to expect the development of an El Nino "Modoki", in which sea surface temperatures would be at their warmest there, rather than in the central Pacific.

As far as its effects on New Zealand went, the event would probably fall somewhere between moderate and weak.

Further, we wouldn't be seeing those effects any time soon, with models suggesting it would be the back end of summer before it was fully established.

Noll put this down to the fact that the warming going on in the equatorial ocean was happening at a faster rate than that in the atmosphere above it.

When the ocean and atmosphere link up and begin communicating – becoming what scientists call "coupled" – El Nino events can properly bed in.

"During strong El Nino events, we tend to see this coupling take place earlier in the calendar year, unlike this year," Noll explained.

"However, given the relative lateness of this expected El Nino event, it may be that it hangs around a bit longer than typical as we head into 2019."

Models indicated a high chance of it persisting through autumn – and even lingering as long as two years.

Forecasting summer

Part of the way that scientists predict what might happen months from now is using what's called analogue forecasting.

The idea was to find years in the past that had climatic similarities with 2018 – but in this year's case, there were few to compare with.

Noll said there weren't any strongly similar "analogue years", but a handful of weakly or moderately similar ones, among them 2014, 2004 and 2003.

When those models agreed on a forecast outcome, the confidence increased - when they disagreed, confidence was lower.

"In the end, we take a consensus of the models, analogues, and our use our experience to create our final outlook."

The climate system wasn't as susceptible to large swings compared day-to-day weather conditions, and was slower to evolve.

When trying to compile a long-range outlook, that slowness could be advantageous – but it still couldn't enable finer-scale predictions, such as picking if Christmas Day would bring barbecue weather.

"In short, yes, there will be changes … the climate system is not static, it is dynamical, always evolving," Noll said.

"We try to put ourselves in the best position to make small changes if necessary - and not dramatic, sweeping ones."