Holding paper placards and standing in the rain outside a Dunedin Ministry of Social Development (MSD) office was an act of desperation for one Dunedin family, after years of homelessness.

"We demand the rights of our children to feel stable and safe," they said.

"Do we have the right as refugees to demand that?"

Months later, the large family of former Syrian refugees say their pleas for a social home are still unmet and a charity worker responsible for their housing has been trying to elbow them out of Dunedin by suggesting they go to the North Island and scam their way into a social home there.

A common symptom of homelessness is exhaustion, caused by constantly moving between inadequate, short-term stays - and being given variable support and advice.

Now imagine the strain if also being nudged to leave the city you were invited to move to as refugees, having come here from a war-torn country with a very different language and culture.

The young family are New Zealand citizens, originally from Syria and invited to settle Dunedin in 2018 as part of the refugee settlement programme.

Described by one Dunedin friend as "lovely and tolerant in the face of adversity, and devoted to their children", the family fled their home in Raqqa to a tent in a Lebanese refugee camp after the trauma of relatives, neighbours and work colleagues being killed.

In Dunedin, stability has been elusive. They have lived at eight different addresses including a cramped and mouldy private rental, an office floor, spare rooms in a friend’s house, motels and - for nearly the past two years - a transitional house provided by the charity Emerge, contracted by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

They are still there - and an Emerge worker has recently encouraged them to travel to the North Island and pretend to be homeless in a bigger city to scam a social house - or, failing that, move into an Emerge transitional house in Hamilton, about 1000 kilometres away.

The family see these suggestions as an underhand scheme to push them out of Dunedin - and they aren’t budging.

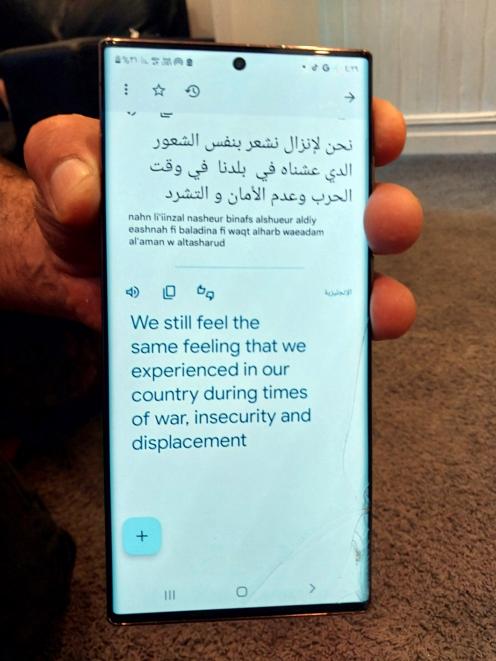

They speak politely about their plight and use the power of Google Translate to get their thoughts across succinctly and powerfully.

Holding up a phone translation, the father says: "We are being threatened and harassed by Emerge and all we want is a stable home for our seven children."

"We still feel the same feeling that we experienced in our country during times of war, insecurity and displacement." The family felt "stressed out, tired, and physically and mentally ill from all the moving around".

They want a government-provided Kāinga Ora social home - right now, here in Dunedin - and don’t want to leave their transitional home until they get one.

When the Otago Daily Times raised their case with MSD, staff agreed the family should remain here, saying it would not be in their interests to go elsewhere.

The family say they have "met many wonderful Kiwis. It is such a good community. All we need is a house".

The chequered road to nowhere

The family are adamant they were asked by the government to leave their first Dunedin house, a private rental. They think MSD indicated they must live somewhere smaller and cheaper after the grandmother of the children - who initially came with the family - decided to leave New Zealand.

MSD disagrees. It also says the family have been offered the chance to view different private rentals.

What is certain, however, is the family have subsequently bounced around various short-term and often unreasonable solutions - and still have no home.

Community members who have befriended the family, and photographic evidence, supports the family’s story that the house they were offered after leaving their first house was a smaller, private rental - and unhealthy.

The family say the carpets were damp, with maggots underneath. The walls were covered in mould. There was moisture running down door frames. There was no fenced outside play space.

The family moved out within weeks. The house made the children sick, they say, including a child suffering asthma.

They slept on the office floor of a local community group for a month, then in a friend’s room for four months. They then had a time in another private rental but also lived in two motels for several months, finally ending up in their current Emerge-run transitional house in April 2022.

The transitional house is perched high above a busy road, with no fenced garden for the young children to play in safely.

The front drive - the only outside space - is broken rubble and surrounded by retaining walls with multi-metre drops on to a road and another property.

Since moving here, the family says it has sought - for safety - a fence around their front drive. One of the daughters asked the ODT recently: "Can we have some fake grass?"

The family has also faced neighbour intimidation. They showed the ODT video evidence of a neighbour parading nude in front of them. The family say they were shocked, offended and felt alienated.

Seeking a Kāinga Ora home

Transitional houses are meant to be for short-term stays of a few months - until a permanent home can be found.

The family is on the waiting list for a Kāinga Ora home in Dunedin and previously had indicated they would consider Kāinga Ora houses elsewhere.

However, more recently they have decided the only safe option for their family’s stability - including a sense of community and continuity of schooling - is to stay in Dunedin and wait for a Kāinga Ora home to become available here.

Prior to this decision, the family say the dad and his son travelled to Auckland - because they thought they were on a housing waiting list there - but when they went into an Auckland MSD office they were told they were not.

MSD says the family had indicated in the past they would live in certain Auckland suburbs and the family have only more recently been put on a waiting list for a Kāinga Ora home in Dunedin.

A Kāinga Ora house had been offered in Ashburton, but the family turned it down.

The family say this is because the house was not in Dunedin, where the children are settled in schools and kindergarten.

Kāinga Ora regional director Kerrie Young says there had been 73 people - in 21 households - settled in Dunedin Kāinga Ora homes through the refugee settlement programme over the past three years.

The number of refugees housed has shown a steady increase, from 11 refugees in 2021, to 29 in 2022 and 33 in 2023.

However, MSD regional commissioner Steph Voight says the family also has a responsibility - as part of its transitional housing agreement - to keep applying for private rentals too.

"The definition of suitable accommodation is not limited to public housing," she said.

The family are aware their priority rating for a Kāinga Ora house is "A19". This is a high priority need score - 19 out of 20.

MSD’s regional commissioner Steph Voight has confirmed taking a private rental "may affect their rating" but "people who are privately renting can remain on the public housing register where their circumstances warrant that".

After so many years of constantly moving, the family are wary of looking at private rentals.

The family says a Kāinga Ora home here would give them long-term stability that a private rental could not.

Community pleas on behalf of the family

Over the years, several medics and a charity have written letters aimed at the housing authorities asking for the family to be housed appropriately, one citing "very stressful life circumstances" for them due to the insecure housing.

One GP letter written a year ago raised the family’s "mental distress and anguish".

"While we appreciate housing is in short supply at present, could I please request any assistance ... to this family to alleviate their distress and cramped living conditions, that is affecting their physical and mental health."

Another letter from a GP pleaded with the authorities to intervene and help the family "who feel they are in limbo and cannot carry on with their lives".

Anglican Family Care wrote to Kāinga Ora describing the family as respectful and tidy but in need of a "place they can call their home where everyone is together and where the children have a space that belongs to them."

Family friend Richard Miller, who opened his doors to the family to stay with him for a few months, said there was a "terrible housing crisis" in the city.

Refugee families are "brought here with support from the Red Cross initially then considered to be like any Kiwi citizen - but in truth they need continued help and support, particularly with authority engagement, to exercise their rights including to housing".

Mr Miller called on more people to reach out to local refugee families who needed friends and help.

Dunedin Muslim Association representative Zaaid Shah has also pitched in as an advocate for the family - and is concerned for their future.

"New Zealand pledged to bring in these refugees to help them," he said.

"We shouldn’t just do it for the sake of international reputation. This family was brought to Dunedin by the government. They must have a pathway to a home and to work."

Mr Shah described the current outcome for the family as "appalling and cruel".

What refugee settlement experts say

Challenges faced by refugees settling in New Zealand include "all sorts of things that are taken for granted by other people" says University of Auckland refugee academic Dr Jay Marlowe.

Settling includes access to housing, but also education, upskilling for jobs, and feeling safe. Understanding matters ranging from tenancy agreements to "social norms" can be hard, with everything compounded by language barriers.

"It is very easy for things to get lost in translation and not be understood."

Housing can be "hard enough for couples, but when there is a large family there can be a real challenge".

Dr Marlowe said he had struggled to get evidence about the numbers of families in Kāinga Ora houses compared with private rentals, but one article had suggested that most were in private rentals.

A study of thousands of refugees between 1997 and 2020, yet to be published, is expected to show that nearly seven out of 10 refugees are settled in places with the highest deprivation and that over time this barely improves.

"This shows the importance of a good start. Where people start is where they end up," Dr Marlowe said.

He stressed, however, that an area with high deprivation may also be where a refugee family finds they can access essential community support.

There was recent evidence of an increase in "inter-regional movement to more urban environments" including to Auckland or Canterbury after initially being settled elsewhere. This is thought to be due to the benefits associated with a more urban environment, including community support, more healthcare and more work opportunities.

Refugees who were settled to low population regions could find it harder to access these things - and also not benefit from long-term support from charities that specialise in helping refugees.

RASNZ, the refugee mental health and wellbeing charity is funded to provide its services to the Auckland area only. Its chief executive Sharron Ward wishes the charity had resources to help in more areas.

Ms Ward says once Red Cross support ends for a family it can be "very difficult, very tricky" to navigate New Zealand society.

"Anyone emigrating to New Zealand can have a difficult journey but it can be extremely difficult if transitioning as a refugee, you do not speak English and particularly if housing is an issue. "This is one of the biggest issues refugees face."

"I am sure the government would love to get people into houses quicker and I suspect they are tearing their hair out trying to work it out."

Refugees’ mental health challenges can include traumatic stress due to their experiences prior to arrival in New Zealand compounded by issues such as separation from family members.

She asked people to consider the huge hurdles refugees had to navigate and consider how "amazingly well" many refugees manage to settle here. "It makes me feel uncomfortable just asking for shampoo in another country where I don’t speak the language," she said.

The charity has cultural facilitators, who help refugees to "normalise" what they have experienced and manage many hurdles, such as talking with MSD.

It would be "wonderful" if there was a refugee centre in every region with mental health specialists, she said, but the big picture showed that overall New Zealand was doing a good job settling refugees, based on the country’s humanitarian values.

Ms Ward supported settlement of refugees across New Zealand for ethnic diversity Her advice to refugees with large families, who had been sent to live in regions outside Auckland, was to stay put.

It can be hard to find large houses in Auckland where the streets are "not paved in gold".