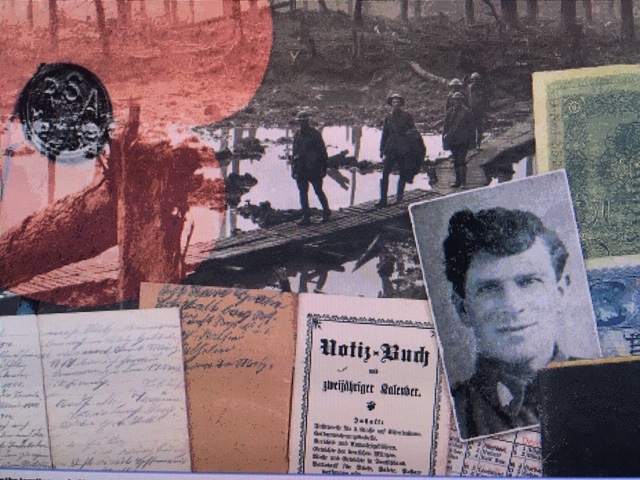

Soldiers in World War 1 were not really meant to keep diaries... not that it stopped them.

Their generals feared vital military secrets might be revealed to the enemy, but those clandestine accounts of life in the trenches have a far greater value today, not for whatever military intelligence might be contained within, but as an insightinto the lives of the ordinary soldiers doing the fighting and dying.

Karl Grahn was one of the lucky ones. The Bavarian infantryman was captured at the Battle of Messines and for him the war was over.

Southlander George Wallace was not so lucky. Although he survived Messines - where his path fleetingly crossed that of Karl Grahn - he was one of hundreds of New Zealanders to die on October 12, 1917, at Passchendaele, the bloodiest day in our military history.

We know that the two men encountered each other thanks to an unusual war souvenir of Sgt Wallace, a diary which through good luck or good fortune made its way back to Southland.

It was not originally Sgt Wallace’s diary, though. The notebook which contains his first-hand account of Messines and his subsequent leave in London was actually the property of infantryman Grahn.

Sgt Wallace does not explain exactly how the book came to be in his possession, other than a tantalising note ‘‘took this notebook off a German prisoner’’.

Records suggest Grahn was probably captured on the first day of the battle, June 7.

Depending on his ancestry, Grahn may well have felt conflicted as World War 1 broke out. His region had been part of France for 150 years, until the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 saw the territory ceded to the Kingdom of Bavaria.

Grahn did not rush to enlist; after leaving school in 1914 he worked for his father asan agricultural labourer while also serving in the cadets.

However, the machinery of war eventually caught up with him, and in 1916 Grahn was drafted.

His thick, now archaic Gothic script makes his story difficult to decipher, but it appears he trained in Landau and Metz before being shipped to the front in March 1917.

The next pages hint that infantryman Grahn’s introduction to war was a bloody one; a flowery, poetic obituary ‘‘to our dear comrade soldiers inthe 5th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment’’ is followed by a dedication to several colleagues.

Grahn’s company moved back into the front line at Messines the day before the Allied forces attacked. Battle records suggest his battalion was entrenched in front of the advancing 1st Otagos the following morning, when he - and his notebook - fell into the hands of Sgt Wallace.

So, also, might infantryman Grahn’s savings. When Mr Davidson bought the notebook it came complete with several German banknotes of the time, some of them being of reasonably high denomination.

GEORGE WALLACE

Like Karl Grahn, George Wallace was a man with an agricultural past.

Born in Mataura in 1888, Wallace was employed at a freezing works when he enlisted in 1915, but on his attestation form listed ‘‘professional cyclist’’ as his profession.

Wallace’s sporting career, which included a podium finish in the Timaru to Christchurch road race, meant he merited an obituary in the Southland Times.

A single man, he shipped to the Middle East and then to Europe as one of many much needed reinforcements for the Otago Rifles.

Enlisted as a private, Wallace’s military career was halted at its beginning by a case of mumps.

However, he soon rapidly made lance corporal and then sergeant.

He was slightly wounded on June 2, 1917, but remained in the field, only be hit again two weeks later.

It was likely after this wound that the then Lance-corporal Wallace decided to sit down and fill the blank pages in the diary he had boosted from a German soldier some days beforehand.

He started with the events of June 3, a day when the Otagos withdrew from the line ‘‘glad to get out as we were all nerve shaken’’ but far from safety as their camp was shelled as they slept.

After a few days of rest, Lcpl Wallace recounts the event of June 7, the day he most likely acquired his diary.

‘‘There we sat still and quiet until 2.30am when word came along to fix bayonets and get ready to advance over the top,’’ he wrote.

‘‘At just on quarter to three there was a terrific machine gun fire, followed by three big mines blown up under the Hun positions by our boys...The explosions were terrific and the whole earth trembled as if it was a terrible earthquake.

‘‘Then we one and all hopped over the bags and attacked old Fritz. Our bombardment was something terrific and we could not hear ourselves speak, but on we went and old Fritz opened his guns on us.

‘‘There were men getting hit and falling all around me, but my luck was in and I escaped unhurt. We captured his first three lines and got a large number of prisoners.’’

Messines was a victory, but an expensive one — 3000 casualties and more than 700 New Zealanders killed in a few days’ fighting.

‘‘We came out about 50 men less than we went in with, so our casualties were not very heavy,’’ he reported.

However, undeterred by a scrape on the nose from a shell fragment, he was back in the line four days later — ‘‘the place is a hell, dead men lying everywhere, and the whole place literally torn to pieces by big shells’’ — but not before being promoted to acting sergeant.

On the 15th, the Otagos withdrew, but two days later Sgt Wallace was back and confronted with one of the Germans’ most terrible weapons.

‘‘Old Fritz was sending over tear gas shells and it was the worst [thing] I ever experienced . . .I was very near blinded and overcome before getting inside.

‘‘Water was just streaming down my eyes and I could hardly open them when a gas shell landed right in the doorway and filled the dugout with tear gas and Ican tell you there was some swearing.

‘‘It was awful and we just had to persevere through it all.’’

Taken out of the line again a day later, the troops were paraded for the Anzac commander General Alexander Godley before Sgt Wallace got a well-earned leave in England.

After visiting London — where he took in the Strand and Buckingham Palace — and Edinburgh, Sgt Wallace’s brief but vivid diary ends.

Wallace’s military records offer a few bare sentences to finish his story.

Back in France on July 7, he was permanently made a sergeant a week later, but also wounded.

After being sent on a course, Sgt Wallace was back on October 6, with two weeks to prepare his troops for the bloodbath which would claim his life, and those of so many of his friends and fellow servicemen.

However, a notebook he took from a fellow country boy means Sergeant Wallace’s war is not forgotten.