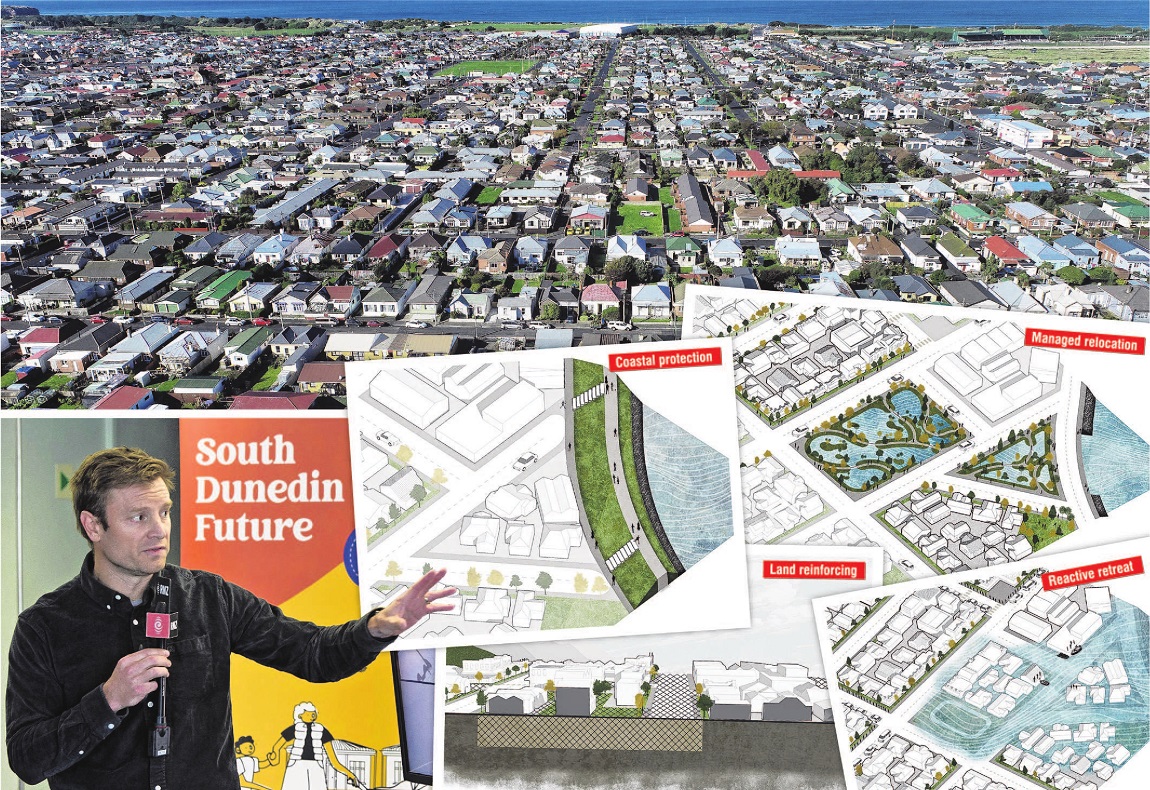

Other ideas to the fore include water detention basins, strategic withdrawal from particular areas, raising the level of houses and modifying drainage systems.

A long list of 16 possible approaches for helping the coastal low-lying urban area adapt to climate change was released this morning.

It is expected a mix will end up being favoured and different sets of ideas will apply to particular places in the coming decades.

The list is generic — comprising classes of ideas, rather than dwelling on specific techniques — and it is to be discussed by both the Dunedin City Council and Otago Regional Council next week.

If the councils approve the content, the approaches will be put to the public for feedback.

Costings have yet to be worked out.

South Dunedin is home to more than 13,000 people, 1500 businesses and a range of critical city infrastructure.

It is built up and has no natural surface water outlet.

The area flooded in 2015 and there has since been extensive study of its geology and groundwater as part of the two councils’ South Dunedin Future programme, which is aimed at improving the area’s resilience amid challenges such as sea-level rise.

Programme manager Jonathan Rowe said emphasis was shifting from grappling with problems to establishing "the kinds of things that are possible".

The intention was to have an adaptation plan in place by 2026.

"The long list shows the many approaches that could be used to make South Dunedin both safer and better.

"Over the next two years there will be many opportunities for the community to help narrow down the list from 16 approaches to preferred sets for different parts of South Dunedin."

A key objective was providing more space for water to keep it out of living rooms and garages.

Mr Rowe described possibilities as ranging from protection schemes such as drainage and water storage to new planning controls and forms of partial retreat.

"Floodable infrastructure" was one new idea that emerged.

This refers to spaces such as parks, carparks and roads being transformed into intentional flood storage zones or overland flow paths to protect other areas from flooding.

Coastal protection options range from sea walls, groynes and breakwaters to restoration of dunes and wetlands.

Mr Rowe said significant challenges were being faced, but there were reasons to be heartened about the future, as a solid plan took shape.

"I’m more encouraged now, having done this work."

One idea floated this year was government support for a voluntary property acquisition scheme for strategic purposes.

Some proposed solutions would require at least a top-up in funding from what the councils alone could afford.

The South Dunedin Future material contrasted a reactive approach to climate challenges — such as declaring an area off-limits after a cyclone — with proactive management, or managed relocation.

The latter involved the methodical relocation of property and infrastructure from areas susceptible to environmental threats before the hazard happened.

Some costs could be avoided through partial retreat, creating a more suitable environment for people to live in, it has been argued.

Possible approaches

- Ground reinforcements

- Groundwater lowering/drainage/dewatering walls

- Land grading

- Conveyance improvements

- Remove wastewater network overflows and cross-connections

- Dedicated water storage

- Floodable infrastructure

- Increase permeability of ground surface

- Coastal protection

- Behavioural/societal changes

- Be ready to respond to an emergency

- Property level interventions

- Reactive retreat

- Managed relocation

- More restrictive building/development standards

- No new development/redevelopment or change of use that may exacerbate risk

Advertisement