It is not often that someone predicts their own death.

Even more unusual is to predict it down to the exact day, and the exact method.

But when Dunedin lawyer James Patrick Ward made an off the cuff remark to a colleague on the night of February 4, 1962, he came eerily close.

When his colleague wondered aloud if they would win an upcoming appeal, Mr Ward assured him they would — unless he got a bomb in the mail in the morning.

An explosion rocked the Security Building in Stuart St, where his office was located, about 9am on February 5.

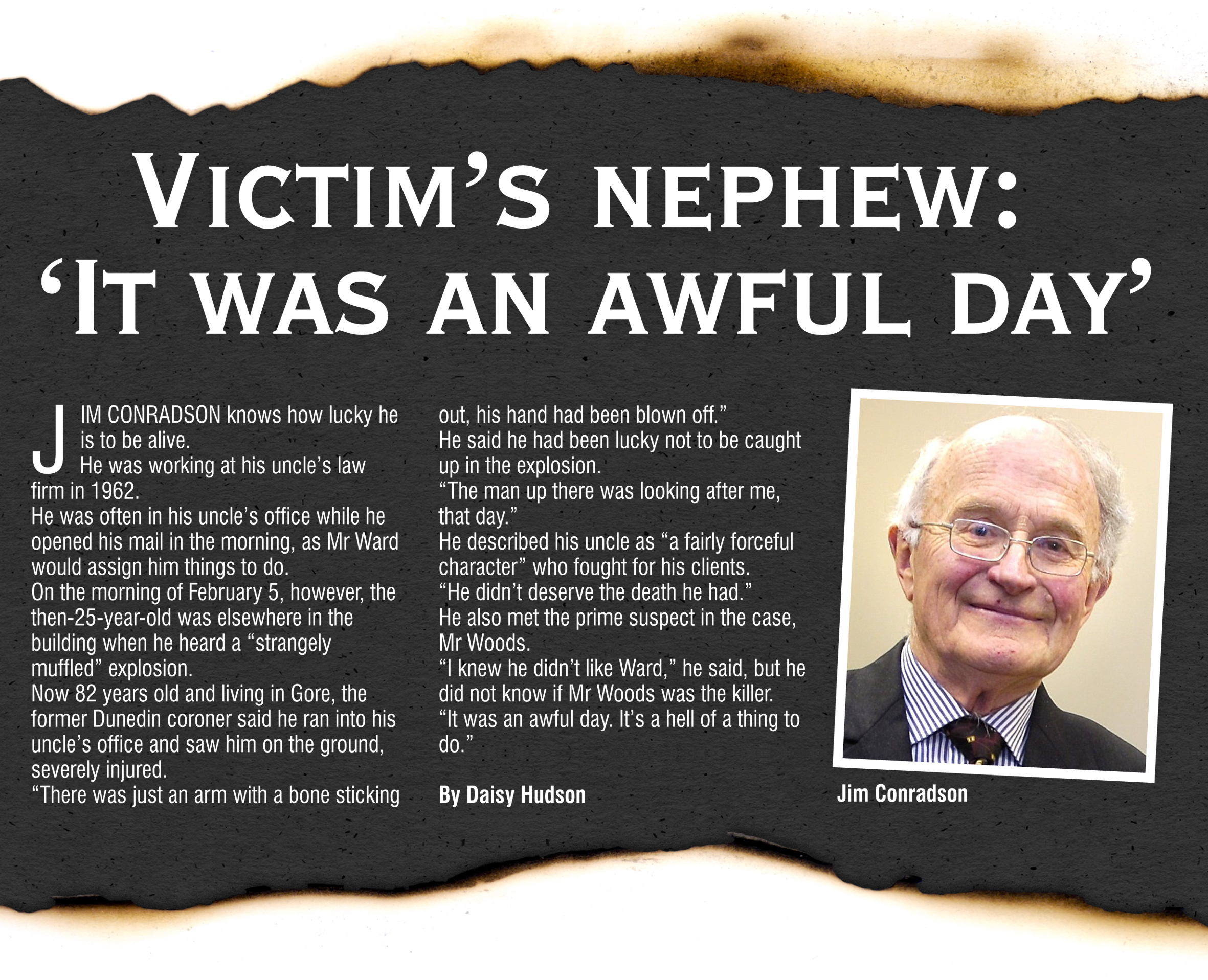

His colleagues, including his nephew, Jim Conradson, rushed into the room and were greeted by a gruesome sight.

Amidst the debris was Mr Ward, lying on the ground and clearly severely injured, a police investigation summary released to the Otago Daily Times stated.

A colleague, Owen Toomey, noticed Mr Ward’s ‘‘left hand was missing and that he had received serious injuries to his chest’’.

‘‘Who could have done this to me?’’ he asked Mr Toomey.

Despite attempts to save him, Mr Ward died in hospital later that day.

His death at the will of an unknown parcel bomber shocked New Zealand, both for the unusual method of killing and the apparent lack of motive.

While he was known as ‘‘dogged and determined and very difficult to negotiate with’’, he was also considered a good husband and father, and was a devout Catholic heavily involved with the church.

His death sparked a high-profile investigation that attracted the country’s top police officers, including national Criminal Investigation Branch head Detective Superintendent William Raymond Fell.

Some details became evident early on.

An examination of the bomb found it was gelignite triggered by an electric detonator, and contained in a wooden box.

The prospect of suicide was considered, but quickly dismissed.

There was no animosity between Mr Ward and his colleagues, and police ultimately determined nobody involved with his cases had motive to kill him.

As the weeks went by without much further insight into the identity of the killer, the murder dropped off the front page and — slowly — out of people’s memories.

It was a frustrating time for police.

They believed they knew who was responsible, but were unable to prove it.

John Daniel Woods

John Woods did not like his brother-in-law, James Ward.

An air force pilot who was decorated for ‘‘courage and initiative displayed’’ while serving in World War 2, Mr Woods had been taught about explosives — and he knew how to make a bomb.

The author of the police summary, Detective Inspector A.I. Knapp, wrote ‘‘we are dealing with a man who, by his very training, has been taught to eliminate all possible mistakes’’.

After returning to New Zealand, he met his wife in 1947, and they lived in Wellington then Whanganui.

It was there that Mrs Woods was told by a senior colleague of her husband’s that he should seek psychiatric treatment.

She went to visit a doctor, who also recommended treatment, but Mrs Woods did not take any further action — she thought his family would be offended.

The couple moved to Dunedin, and then to Alexandra, where their marriage broke up.

They both moved back to Dunedin, and while Mrs Woods attempted to reconcile with her husband, he refused.

Mrs Woods gradually became close with her sister-in-law, Helen Ward, and her husband James.

Their friendship became an increasing bone of contention with Mr Woods, who repeatedly demanded his family cut off his wife.

Police described Mr Woods as having ‘‘an obsession’’ with the relationship.

‘‘That obsession was that while the Wards were associating with his wife, they were causing a rift in the family, and that rift was having an injurious effect on the health of his parents.’’

Mr Woods also made threatening statements about Mr Ward and his son on multiple occasions.

On the Friday before the murder, Mr Woods phoned Mrs Ward and said ‘‘Are you sure you won’t reconsider your decision before it is too late? You will be sorry if that is so, you are a proper Gestapo and it is a crowd like you that starts a war’’.

Mr Woods also became angry about apparent snubs and a lack of sympathy from Mr Ward over the issue.

Police suspicions

As Mr Woods was the only family member considered a suspect, he soon became the main focus of the investigation.

When interviewed by police, he strongly denied having sent the bomb, or having threatened Mr Ward and his son.

He did disclose he had the knowledge required to make a bomb.

In the police summary, officers said they found Mr Woods difficult to interview as he knew they had ‘‘little actual evidence against him, and if he persisted in his denial the interview must reach a stalemate’’.

Police also noted that members of Mr Ward’s family viewed Mr Woods as a suspect.

However, there was no physical evidence to tie him to the murder.

‘‘It will be quite useless interviewing him again

unless we have some further facts to talk about,’’ Det Insp Knapp wrote.

‘‘We are endeavouring to get those facts.’’

Police were never able to get said facts.

Mrs Ward died without knowing who killed her husband, and Mr Woods died without being either charged, or cleared, in relation to his brother-in-law’s murder.

The case remains open, but unsolved.