The story Peter* tells is shocking. He has said that when he was just 8 years old, and living at a Presbyterian Support Otago’s children’s home, he was raped weekly by an older boy and sexually abused off-premises by a psychiatrist.

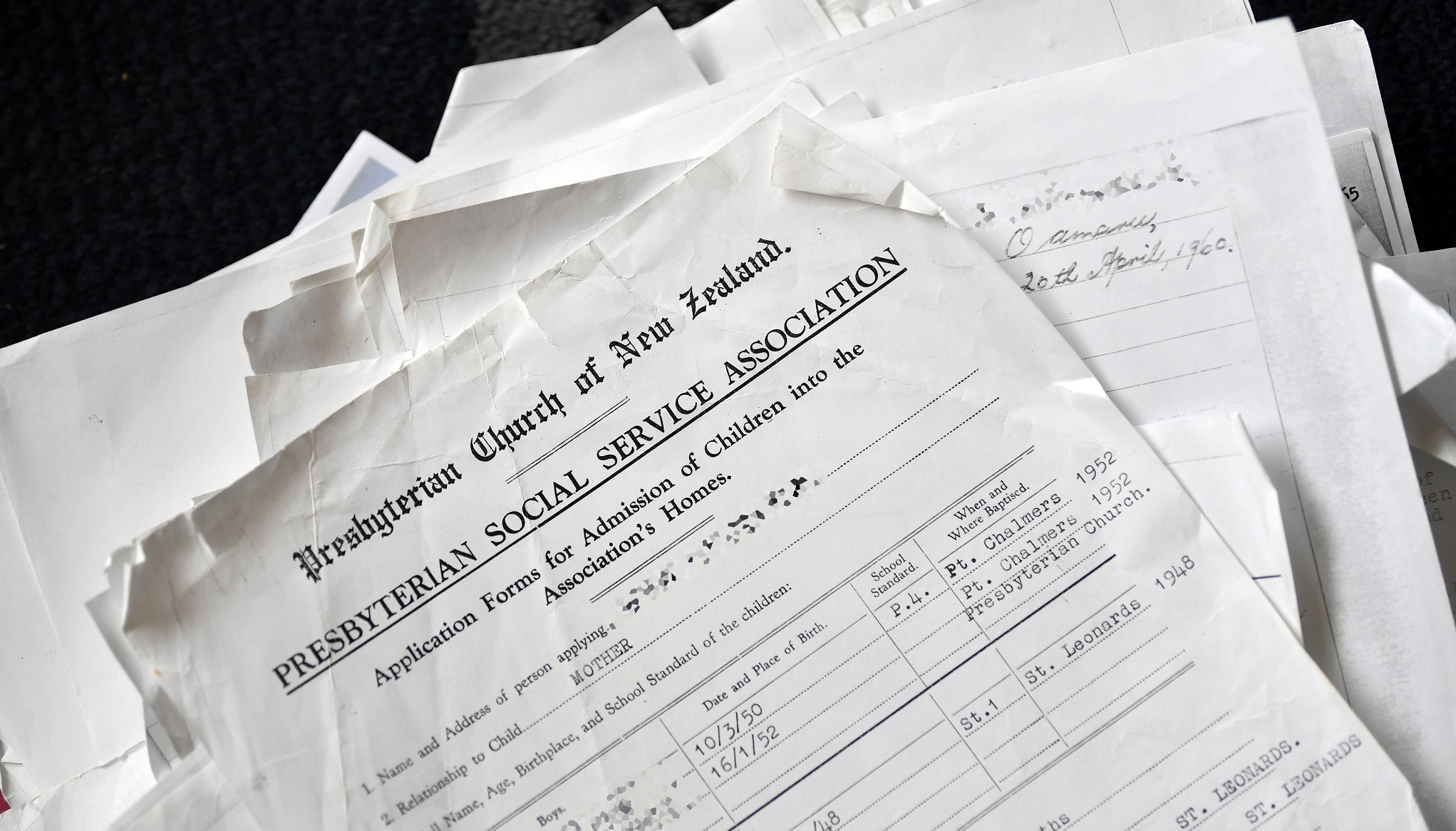

His story has come to light during the investigation of the bombshell email of February 3, 2016, between PSO chief executive Gillian Bremner and lawyer Frazer Barton about Ms Bremner’s idea to destroy records of children who had lived in PSO’s homes.

The destruction went ahead the next year and Ms Bremner and Mr Barton, and other PSO board members, have been hauled over the coals by the media. The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care had talked about the Bremner-Barton email and the records’ destruction in its final report.

Two lawyers have lodged formal complaints about Mr Barton with the Law Society relating to the "informal advice" he provided to Ms Bremner. However, the email itself begged more questions.

The first part of it had asked whether a former children’s home resident’s file should be released to their lawyer. Mr Barton had answered yes, but was it released and what was in it?

It was, most likely, the file about Peter, who lived in PSO’s Glendining home in Dunedin and is now in his 40s. His lawyer had written to PSO the week before the Bremner-Barton exchange, asking for the file, and it was sent over in February.

In the second part of the email, revealed by the Otago Daily Times last month, Ms Bremner asked whether it was best to destroy records and proposed it happen when an employee who had a "connection" to the records "retires in the next 5 years". This would leave "no connection and frame of reference to that bit of history". Mr Barton had answered "yes, I think so but at an appropriate milestone or anniversary".

But who was the employee and were they shunted out around the time of the record destruction, which happened about Christmas 2017 under Mrs Bremner’s leadership?

The ODT has discovered the employee was Carol*, who has agreed to talk anonymously. She says the mention of herself in the email is "deeply unfair — it’s like, wait until she goes and then we will get rid of all of that".

She condemned the Bremner-Barton email and record destruction as "despicable ... just awful ... unbelievable really" and told her story.

Carol’s career

Carol had worked at Glendining from the early ’80s, joining as a "supervisor". She remembered Peter, and the older boy, and Peter has said Carol was his main carer there.

When the home shut down in 1991, due to government funding reprioritisation, Carol was put in charge of the children’s records — for 27 years.

Around 2018, shortly after Ms Bremner orchestrated the records’ destruction, and the royal commission was ramping up to require charities to submit evidence, Carol says she was offered radically reduced hours. She left, after 36 years’ service. Ms Bremner jumped ship a year later.

In January 2021, an email exchange between PSO staff members, forwarded to the royal commission, described someone as having "guarded" the records "with intensity". It was Carol. The records were in a locked cupboard in the basement and she had the key. She dug the records out for former residents who "came from far and wide" to look at them, she says.

"I faithfully guarded them and allowed people to have access to them."

She sat with people while they looked, or gave them space to look alone, with an offer to talk if they wanted.

"I thought it was a privilege to do that."

She says that looking at the records "could sometimes be quite distressing ... Some had good experiences and some not so good ... . Some had a terrible time".

Peter’s time was terrible and his records had gone straight to his lawyer.

Peter’s story

Peter’s records contained warning bells. One social worker’s note in his file, from 1990 when he was 8 and living at Glendining, describes a "behaviour lapse" at school, linked to "problems at the cottage over last weekend re activities of [name of an older boy]".

The older boy, aged 15, had "quite a hold" on Peter. That "hold" was anal rape, Peter has said. He said that after the first rape, he raised a concern about the older boy’s sexual behaviour as best he could to Carol and another PSO employee, but couldn’t articulate that it was rape. He was then raped weekly, in bushes on the home’s grounds.

He said he was also sexually abused by a visiting psychiatrist, who was later imprisoned for sexual abuse of another child.

Peter has had a hard life but in one respect he was lucky. His lawyer asked for his PSO file before the other files were destroyed — and his case was settled, including an apology.

Other former residents will never get their files. They no longer exist. Claims of abuse can still be made, but important evidence may have gone.

The timing of the files’ destruction, just before the royal commission opened, was deeply suspicious. The records’ destruction is not — as yet — the subject of a police investigation. Police say they are "assessing" the commission’s findings to determine any action.

Carol says she wasn’t involved in the actual destroying. She suggested the ODT talk to her old PSO line manager, Paul Hooper, who works for Oranga Tamariki, and ask him. He refused to talk. Mrs Bremner is thought to still be living in Africa and is uncontactable.

An issue of ethics

The destruction raises a stark ethical concern about Carol’s second role. By the time she left her first role, allegations of abuse in faith-run institutes were circulating. Was it appropriate — due to the potential conflict of interest — that Carol’s bosses put her in charge of the records?

Karin Lasthuizen holds the Ethical Leadership chair at Wellington School of Business and Government. In her opinion, PSO’s leadership should have placed the records under someone else’s care, outside the organisation. The government should have provided a central depository for records when it withdrew funding for children’s homes. The risk was too great, as the later destruction proved.

Carol shouldn’t be blamed for being required to look after the records but "shouldn’t have been given that responsibility. She wasn’t working in archives; she just got the archives".

Carol describes her second role as a "huge responsibility" and had never considered there was an ethical conflict. She now agrees, on reflection, that a government depository could have been the "right thing to do ... if you think about all those sad stories".

She remembers Peter, the older boy and the psychiatrist. The home was supervised, and staff were very aware of the older boy being oversexed and were "pretty good at keeping a watch", she said.

However, she also says it was "very, very hard ... We were as careful as we could be". Frontline social care is "very, very difficult".

"You always get predators that come along ... It’s a minefield really."

David’s records

David*, who lived at Glendining in the 1950s, has positive memories about his childhood that he has documented in an unpublished book.

However, he complains about how his request for his file was handled. He asked for his file in a letter in May 2002, quoting his rights and demanding an "immediate response" but it took four months for his file to arrive.

It is a rag-tag collection of correspondence and forms, containing worrying facts. From the age of 6, he was sent away on buses to live with families he had never met before, during school holidays. Aged 12, David’s mother was told not to sign her letters to him with the phrase "your loving mother".

The PSO director of child care wrote a month later: "I won’t say he has improved greatly but on the other hand he is no worse."

When David got his file from PSO it came with a letter from Carol. "It was not my intention to censor the information held by us," she wrote.

"I was concerned that you had enough support as sometimes when you receive information about your past it can open up things in an emotional way ... I would just like to comment on files written in these times. They were not written with the view that the person involved would ever read them."

David says he felt disrespected by the delay and Carol’s letter and PSO offered him no support. PSO should be "honest". He thinks PSO hadn’t wanted to share details or be accountable for its actions.

Carol says she remembers David — and never denied anyone access to their records.

Settling, slowly

In 2005, in response to negative publicity about how a sister Presbyterian charity based in Wellington had responded to abuse allegations, PSO issued a statement to supporters. PSO had "examined" its complaints procedure. If it found itself in a "similar situation" it would treat people with "respect, empathy and compassion and take the time to listen and do whatever necessary to right a wrong".

Peter’s lawyer asked for Peter’s records a decade later, but it still took six years for PSO to settle Peter’s abuse claim.

It is understood that at the end of April 2017, the charity said it needed more information. In July 2017, PSO rejected some allegations and didn’t address others. When pressed the next month, the charity refused to settle and deflected part of the claim to a government agency.

That was under Ms Bremner’s leadership. Peter’s claim was finally settled in 2021, under the leadership of the next chief executive, Jo O’Neill.

David calls on "Glennie kids" whose files were destroyed in 2017 to rally.

"They need to stand up, speak up and say: why have their records been destroyed?

"My files belong to me, my family, my loved ones and what’s more they belonged to my mother who is no longer here. She deserved this right." — Additional reporting by Tim Scott

*names changed to protect the vulnerable

Abuse and alleged abuse at PSO

What the centennial book said

In 2006, PSO published a book about its first 100 years. Historian Ian Dougherty wrote it and says he was not given access to the children’s records. He used committee minutes and other sources that revealed abuse and allegations of abuse.

The charity’s children’s homes had started way back when PSO was the founding branch of the Presbyterian Social Service Association (PSSA).

In the 1920s, the charity’s first employee and Presbyterian minister, Edward Axelsen, admitted four charges of indecent assault on boys aged 13 to 17.

He had tried to hypnotise the boys before assaulting them. He was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

In the 1970s, a girl complained she had been sexually abused by the husband of a Glendining staff member. Police had pressed charges but stopped when he had a stroke.

In 2004, PSO was served High Court papers about a physical abuse claim alleged to have happened in the 1950s. The charges were discontinued due to the alleged offender’s death.

In late 2005, another allegation of physical and sexual abuse in the 1950s was received and settled. Mrs Bremner told her board that there was a "potential" for further complaints against the same deceased staff member.

Mr Dougherty says he circulated a draft of his book to senior PSO staff and board members and at least one person within the Presbyterian Church. Some expressed concern about mentions of abuse and he received a "diatribe" seeking removal of criticism of Presbyterian ministers.

He says Carol objected to the abuse mentions. She says she doesn’t remember. The book was allowed to go ahead.

What the royal commission heard

In 2022, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care — which heard more than 2000 survivor stories from across New Zealand — revealed that PSO had admitted at least six allegations of abuse and settled some cases.

PSO chief executive Jo O’Neill — Mrs Bremner’s successor — acknowledged to the commission that many more survivors might not have come forward.

The six cases likely included Peter’s abuse and another boy abused around the same time, as well as cases flagged in Mr Dougherty’s book.

One woman had told the royal commission about being abused at Glendining in the 1950s. She was beaten, locked in a cupboard and tied to a flagpole. She was also raped by Presbyterian Church parishioners when sent to visit them, and by the home’s gardener.

Her lawyer says PSO settled her case in 2012 and she died three weeks’ later.

Similar abuse in PSSA care was raised with the Presbyterian Church, after the commission opened its inquiry. Anna* lived in two PSSA homes in Invercargill and said she was raped by a paedophile ring of church members in the late 1960s in Otago and Southland, including in school holidays in their homes. Her claims were accepted by the church, who offered a cursory $15,000 compensation.

What was in the children’s records?

The destroyed files would not have documented sexual abuse carried out in the shadows but it is likely they contained details of physical abuse.

Ms O’Neill, who had submitted evidence for the royal commission, had included a statement from an unnamed member of staff who said there had been "sanitising of notes because people wouldn’t understand the treatment that was dealt out back then".

Examples included washing a child’s mouth out with soap and water, hitting children on the side of their heads and locking them in rooms. "That kind of thing was OK then, but people would be horrified now," the staff member said.

After the records’ destruction, the charity retained a spreadsheet of children’s names and dates they were in PSO’s care. A member of staff, tasked with submitting the spreadsheet to the royal commission, wrote a statement in December 2020 about a conversation with another member of staff.

"I stated how sad it was that each child’s life amounted to one line ... and that I had been unable to find any further files, either electronically or physical files ... . A staff member stated that I wouldn’t find anything ...

"I indicated my surprise at this situation and why files would be destroyed and that there must have been something in the files that could have been detrimental to PSO, and he said there was, very detrimental."