Mary Williams investigates whether it’s possible to take the heat out of retreat by relocating them slowly.

There's no doubt about it. Houses will be lost in South Dunedin due to climate change causing a more watery future. How that happens, however, could be simple or complicated.

The simple way means waiting for disaster. A rising sea, more intense rain storms, emerging groundwater and catastrophic flooding are all predictable. Houses not built to withstand flooding will have to go and will lose their value.

The complicated way is to tackle things head-on now, through a managed process that, at its heart, includes relocation of people.

South Dunedin Future manager Jonathan Rowe says his goal is to "undemonise a managed retreat and push it into a place where people understand it".

A plan for land use change would aim to mitigate, for as long as possible, the impact of more water and include movement of people to keep everyone safe.

The South Dunedin Future project — set up by the Dunedin City Council and Otago Regional Council — is tasked with devising such a plan through a process which includes expert and community consultation. A list of 16 proposals was published earlier this year and community feedback sought.

Most of the things on the list aim to help people to live in South Dunedin as long as possible by managing the storage and removal of water. Number 14, however, is about relocation of people. Numbers 15 and 16 are about restricting and banning buildings in areas that will be most at risk sooner, and intensifying development in lower risk areas too.

"Land use change is required to get us out of this. Doing it with red stickers after the Christchurch earthquake is one way it can happen but there are lots of other, probably better, less impactful and more community focused ways," said Mr Rowe.

"If we can figure out how to do that proactively over time and on a voluntary basis then we can achieve some great outcomes rather than having this enormously disruptive fracturing of society that would come with moving hundreds of people all at once."

Within a managed plan, people will have to move for three reasons.

The first reason is to get people out of spots predicted to flood worst and first.

The second reason is to replace some low density housing with higher-density housing in areas that are safer for longer. This means people who are being moved from flood prone spots could relocate to other parts of South Dunedin if they wanted to stay in the area. A future development strategy for Dunedin is hoping for no net reduction of people in South Dunedin in the next 30 years.

The third reason is to make way for infrastructure that aims to help remove and store as much water as possible, for as long as possible, such as more pump stations or green areas.

Eleanor Doig is an out-spoken South Dunedin community advocate. The six-monthly South Dunedin hui is coming up next month and as Ms Doig tells it, people need to keep pulling together to combat a "thread of anxiety".

She brings things back to the wellbeing of individual homeowners.

"The main thing is that people are fairly compensated if their house needs to go." She has views on who should be at the front of the compensation queue.

Despite the rising waters and because building rules are yet to be significantly restricted here, and land prices are cheaper here, private developers are putting up townhouses and large beachside villas — and people are still buying them.

Other people have been in their homes for years. Carolyn Sanders, 75, lives in Prendergast St in a small, old home in a row of cottages built originally for workers at the Hillside Railway Workshops. Some cottages show signs of dilapidation but she keeps hers neat, with brightly painted blue windows and a tidy garden out the back.

Ms Sanders moved here 11 years ago after a working life spent milking cows. She bought the house for $132,000 on the recommendation of her daughter, who lives in Port Chalmers.

"It was the cheapest in Dunedin at the time," she says. Her insurer tells her the house is now worth three times the price.

She has a picture of the 2015 flooding on the street, but has no intention of moving — it’s a friendly place, she says. She hasn’t take part in the community consultation by South Dunedin Future.

"There have been meetings I could have gone to. But there’s no point me stressing out. I hope they are doing the right thing at the right time and make the right decisions."

Any homeowner whose house may be earmarked to go would say it is preferable that a decision is made to buy their house early and fairly with government funds than when the value of their asset disappears due to rising waters and market forces.

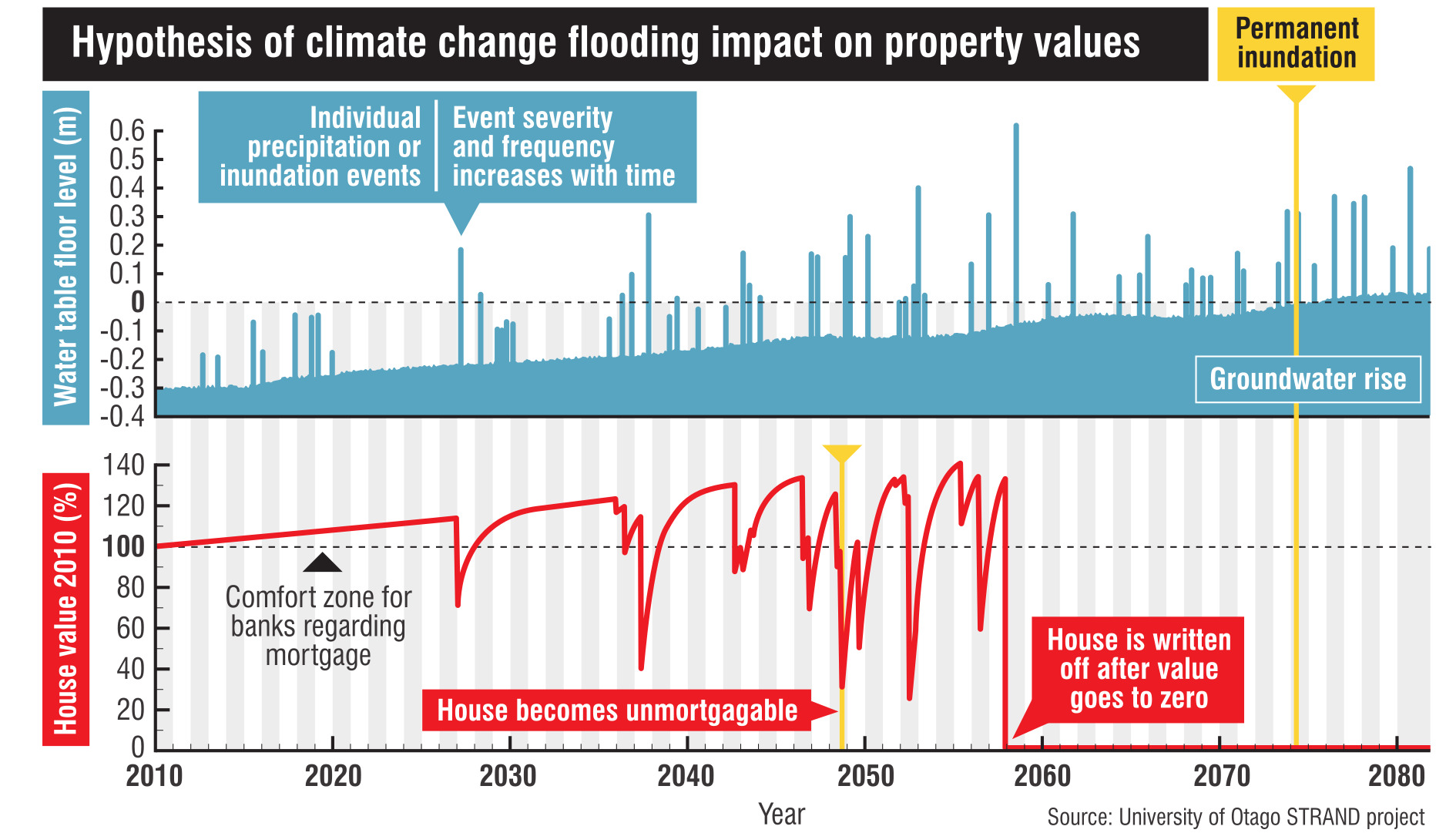

At the University of Otago, a multi-disciplinary research team of experts in earth sciences, surveying and economics, is determining the impact of climate change on property values. The team’s project, known as Strand, hypothesised at its launch three years ago that if an area suffers increasingly frequent and intense flooding it will eventually become impossible to get a mortgage on a property there. The value of buildings will consequently slump to zero.

Since then, the academics, supported by the Marsden Fund, have been devising and running thousands of models to compute when this could happen.

Associate professor of geographical information science Tony Moore, one of the team’s co-leaders, says that despite unknown variables such as the speed of sea level rise, the project’s findings will "provide considerably more knowledge so people can be best informed".

Findings will be published early next year and be of keen interest to homeowners, property developers, insurers, banks and the city council.

In the meantime, the South Dunedin Future team are continuing their community consultation about the 16 ways to manage the waters. Feedback notes scribbled by attendees at a recent public event about the 16 proposals painted a fearful picture of number 14, managed relocation.

"Unaffordable, unrealistic," wrote one. "Where could we even go? We don’t have space. Housing costs would skyrocket."

"How to buy out at a fair price?" asked another. "Most South Dunedin housing would not provide enough to purchase new builds. Many aged [people] could not get mortgages to cover the difference."

"Voluntary buy-outs are a good solution but only a last resort," a third read.

Mr Rowe, from South Dunedin Future, says it is important to listen to what people say and help them to understand better.

"Managed relocation is the thing we do first because it is going to be part of everything we do.

"All 16 approaches require some sort of retreat because they require some sort of land use change.

"It is that swapping of land use that reduces risk and moves people out of harm’s way."

However, the plan will require cash. Lots of it. Last August, Mr Rowe, with the support of council chief executive Sandy Graham, submitted a bid to government for an acquisition fund, to enable it to start buying properties. It sought $26 million a year for the next five years, starting this year.

Broadly, this meant the council would be able to start to buy about 1% of residences a year. If that rate of purchase continued, it could hypothetically move 100% of the area’s population over a 100 year timeframe as the waters continued to rise.

A decision to give any money has yet to be made by the new government. In February this year, the council kicked off its acquisitions by shelling out $13.2m from its own capital expenditure budget for Forbury Park.

Environmental Defence Society policy director Raewyn Peart says managed relocation is "extremely difficult. How it is managed goes to the heart of who we are as a country and as communities. We need to know how we are going to support each other, who we are going to compensate, and whether we are going to enforce or entice people to leave homes.

"South Dunedin is at the forefront of all this as it has already suffered flooding that will get worse."

Ms Peart points to other aggravating factors in South Dunedin, including poverty and the developments shooting up under existing building regulations. The council is reviewing minimum floor heights in its building rules at present, but has declined to say when this review will finish or what else it may stipulate.

However, Ms Peart stresses that managed relocation is preferable to a reactive retreat after a disaster.

"It is clear it is much more cost effective in terms of both financial and social costs to get ahead of the game and move people out of hazardous areas in advance of things happening, rather than clear up the mess afterwards."

She points to the "massive cost" of the clean up after Cyclone Gabrielle.

Managed relocation can be progressively staged, says deputy director of the Helen Clark Foundation Kali Mercier.

It can be planned to happen at certain "trigger points", for example when flooding starts to become more severe and frequent in an area and interim mitigation approaches, such as more trees and green spaces to soak up water, can no longer cope.

"Being really clear about those trigger points helps the community," she says.

"You don’t want to take everyone out all in a rush unless that is what the community is wanting.

Many people may want to stay as long as it is reasonable to do so and for many reasons, she says, ranging from having family here to finding it practical to live on the flat. There is a higher turnover of homes here than in other areas of the city, but there are also people who settled here years ago, or generations ago.

Sustainability research professor at the University of Otago Janet Stephenson says South Dunedin’s diverse community — including disabled people, the elderly and families — has a sense of cohesion, helped by a shopping centre, beaches, parks, schools and now a library and community centre under construction.

"It is established and vibrant.

"Not the kind of clean city vibrancy that the model of competitive cities buy into, but actually much more gritty and important and real."

Community consultation about the future is important. It demonstrates empathy and inclusion at a time when people may suffer strong emotions and find it challenging to consider the future with clarity. The consultation also comes after a period when there was a "simmering sense of the area being left behind, forgotten and not resourced".

That is changing, she says, but so is the climate. People have to come to grips with the world not being permanent, that they might have to move.

"To engage with the community in these circumstances is engaging with massive emotions that are increasing probably, over time, as the real impacts of climate change start to hit."

Her hope is that people will continue to demonstrate adaptability in the face of adversity.

"We tend to think we have to live as we do now, but during Covid we actually made extraordinary decisions that no-one thought was feasible, like closing borders."

Ms Doig points out that some people will inevitably never come along to South Dunedin Future events or respond to surveys about what should happen. She had, in the past, "fretted" about reaching everyone.

A caravan offering free coffee would be a good means of attracting more people to talk about their views, she suggests. "But the fact is some people will not even do that.

"They may be so stressed about other things such as putting food on the table they can’t spare the time to talk.

"I’ve been there and it fills your head. You can’t even begin to think about this other stuff."

Ultimately, she hopes that those who are not consulted may get a sense that others were, and their views were represented. "The South Dunedin Future team have not put a foot wrong.

"They are listening as best they can. We are leading the country in community engagement."

She takes a deep breath. "I just love it here."

Advertisement