Forty years ago next week, a large slab of land the residents of Abbotsford had built their lives on began its final slip, carrying away 69 family homes with it. However, the disaster had been a long time coming. Chris Morris reports.

Rex McCay can still recall the "awesome" sight that met his eyes on the night of the Abbotsford landslip.

The 28-year-old had only recently been appointed as the town clerk for the Green Island Borough Council, which by then had assumed responsibility for the suburb of Abbotsford.

In the months following, the increasing pace of land movement there had been consuming much of his council's attention, as underground water pipes began to fracture, roads buckled and cracks spread across residents' homes.

Nevertheless, few people expected the events of August 8, 1979, to unfold the way they did, when the hillside finally began to slip at 9.07pm.

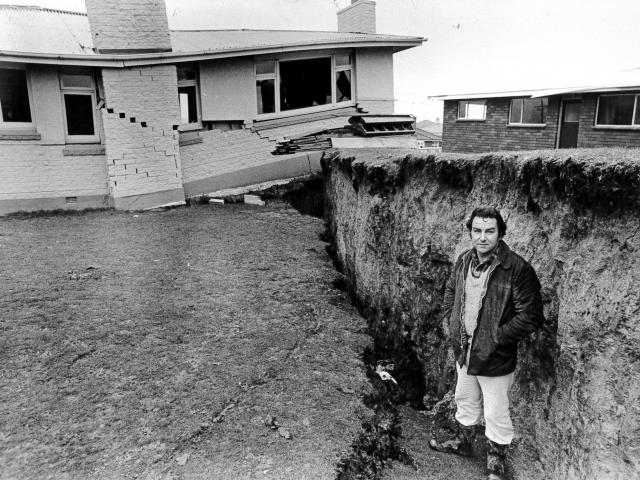

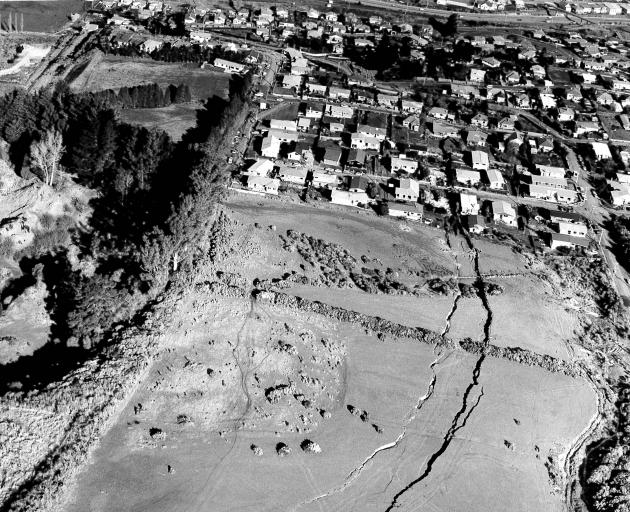

By the time it was over, an 18ha block, comprising 5million cu m of earth up to 40m thick, had dropped 50m down the slope over 30 minutes, taking entire sections of streets and 69 homes with it.

Some homes plunged into the void that opened up, measuring 150m wide and 16m deep in places, while others rode down the hill on the slab.

So, too, did a group of 17 residents, marooned on the moving island of land and screaming for help as chaos raged around them.

Mr McCay arrived at the scene minutes after being alerted to the unfolding drama, and watched in awe as the landslip moved, slowly but inexorably, down the hill.

"It was just an absolutely amazing sight. There were houses falling into the [void], there were cars falling in ... electricity lines were cut and there were sparks around the place, there were emergency services lights, there were fire engines, and there were ambulances arriving.

"I had never seen anything like it before, and I've never seen anything like it since."

Miraculously, serious injury and death were avoided, but the damage bill was eventually to top $10 million.

It was a unprecedented event in New Zealand history - but one thing it was not was a surprise, Mr McCay said.

For months, his council had been repairing underground water pipes which fractured repeatedly, as land movement increased, even as authorities met to decide their next steps.

"And then we sort of realised, over a period of time, that there was something more serious happening than what we originally envisaged.

"We thought it was just a bit of localised subsidence, but then when the [void] started to open up, then we obviously started to get concerned about the safety of people.

"We were dealing with something we'd never come across before, and no other local authority had come across that sort of thing before."

The first signs of trouble had come earlier, as a Commission of Inquiry was eventually to make clear.

In 1969, a decade before the disaster, one homeowner had noticed hairline cracks spreading across a wall of his Christie St house.

Attention focused on nearby Harrison's Pit, a quarry at the bottom of the hill, where 330,000cu m of sand had been mined for the construction of Dunedin's Southern Motorway over the previous decade.

Concerns were raised with the Ministry of Works, which said not to worry, and an insurance company refused to pay out.

However, by 1972, cracks were spreading across the man's front lawn, as well as his neighbour's, and other homeowners were finding cracks in doorways, pathways, walls and driveways.

Also, by 1979, the pace of land movement was increasing.

On May 30, a council-owned water main was found to have pulled apart at the joint - suggesting ground movement.

Engineers were called in, and a full-scale investigation was launched on June 1, after the same water main fractured again and other signs of movement were identified.

By June 12, the survey marks had moved by between 3mm and 23mm over 11 days, more damage to houses had been detected, and Civil Defence staff noted a "fault line" emerging in Abbotsford.

Three days later, a graben - the geological term for a depression of land between steep slopes - began to appear on Mitchell St, and more fractured water mains and sewer pipes followed.

Six more houses were later found to be "doing the splits" over the widening fault line, while 30 more were on "moving ground".

Cracking and pipe fractures continued into July, but authorities agreed any movement was likely to continue at the same pace.

By July 17, ground movement could be physically observed at one location, and a wider evacuation was being discussed, but the consensus remained that any break-up would take 24 hours, giving "ample time" for an evacuation.

Soon after, parts of nearby Miller Park began to bulge, and land movement accelerated to 20mm a day.

By then, the Earthquake and War Damage Commission had been warned a "significant increase in movement rate could occur with little or no warning ...".

Authorities continued to meet, and agreed no wider evacuation was needed yet, but began planning for a worst-case scenario of mass land movement with only two hours' warning.

On July 24, residents were warned of the possibility of sudden movement, significant damage and the potential for the whole area to become uninhabitable.

Publicly, however, media were told there was "no possibility of a sudden collapse or land avalanche".

Also, as residents angry at an insurance freeze and other issues began instructing solicitors, concerns about legal liability meant access to information was restricted.

Then, as more evacuations were ordered, the pace of movement increased to about 50mm a day by July 28 and to 100mm a day by July 30.

By August 3, movement of 148mm a day was recorded, and the void between the two blocks of land was predicted to reach 4m by August 12.

Three days later, after much debate, a civil defence emergency was declared and a formal evacuation - to be completed by August 12 - began.

On August 7, a property owner, Ken Scurr, found two large trees had fallen overnight by the movement of land, and feared a "break off point" would be reached when two large cracks in the ground met.

The next night, the residents of six houses - in Mitchell and Edward Sts - remained inside the slip zone.

It was 8.30pm on August 8 and, just over 30 minutes later, the entire block began to slide.

A year after the disaster, a Commission of Inquiry's final report identified a series of factors contributing to the disaster.

That began with the geology itself, which meant that, unfortunately, houses had been built on a sloping layer of unstable clay over sandstone.

Once saturated, as it had been by heavier-than-usual rainfall in recent years and a leaking Dunedin City Council water main, which possibly contributed, the structure was ready to slip.

The inquiry also identified the excavation of Harrison's Pit, at the bottom of the landslip zone, as contributing to the slip.

The Green Island Borough Council was also criticised for allowing development to continue in the area, despite earlier warnings of instability, and for a lack of information to residents early in the unfolding drama.

However, the council's subsequent efforts, in pushing for a state of emergency declaration, its actions immediately before the landslip and following the disaster, deserved "the highest praise", it said.

Mr McCay, speaking from Western Australia this week, said development in the area was already under way - and therefore a fait accompli - when his council had assumed responsibility for the area in the years before the disaster.

Also, although the evacuation had been run by Civil Defence staff, the council had been "quite specific" about wanting residents to leave, he said.

Some people wanted to "push the boundaries" to try to retrieve their property, but they went in knowing the risks, he said.

"They [Civil Defence] obviously did what they thought was right, at the right time, but today I guess things might have been a little bit different."

The emotions of residents caught up in the disaster - who lost their homes and battled for insurance payouts - were understandable.

Payouts had eventually begun to flow, but "it was a traumatic time for everybody" and compensation could not fix everything, he said.

"There's an emotional attachment with your property. To lose it, it's going to leave a scar."