To go one step further — how much energy would a penguin gain from eating a squid arm?

No-one really knows what goes on underwater when humans are not around to witness it.

But University of Otago marine scientists are hoping their new research technique will help unlock the underwater secrets of marine wildlife.

Miniature cameras or sensors are often attached to animals such as penguins and seals to allow scientists to observe daily activities like their predator-prey interactions and decision-making.

However, questions remain about specific details of their feeding behaviour, such as prey selection and foraging strategies.

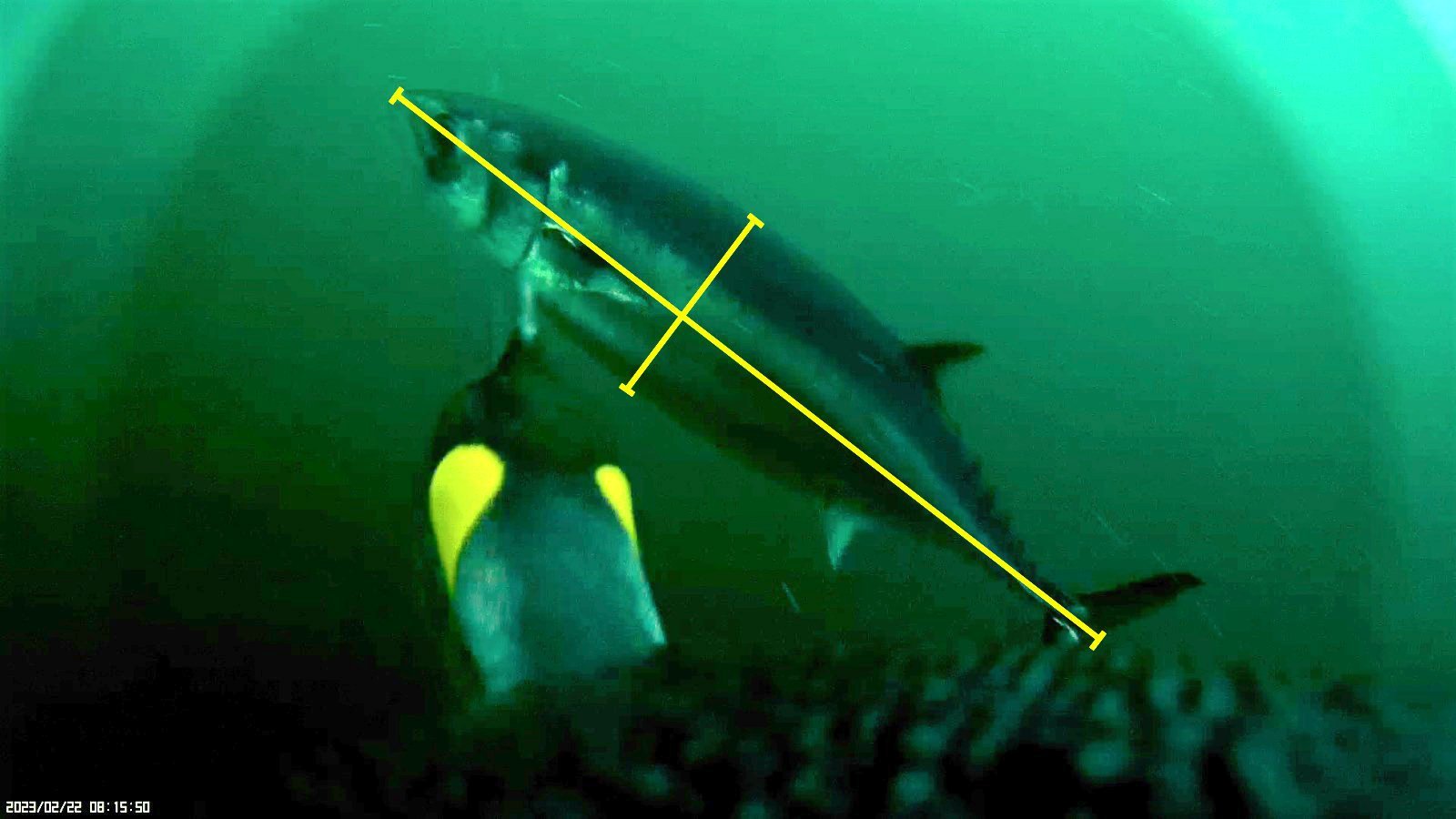

In a recent study, Otago researchers were able to analyse footage from animal-borne cameras on Humboldt, king and tawaki/Fiordland penguins, using image-measuring software which converts pixels into actual measurements, allowing them to estimate the energy content of the penguins’ prey.

Lead author and marine sciences master’s degree student Owen Dabkowski said it was a major step forward for marine biology.

‘‘Our work will explain why animals target certain prey over others, or how much energy they gain in a single feeding period, compared to how much energy they expend.

‘‘The new technique will provide a unique perspective for analysing diet composition and foraging behaviour, revealing previously unseen interactions that occur underwater.’’

Mr Dabkowski said the information was important because some penguin species would travel from New Zealand all the way down to the subantarctic and back to forage for food.

‘‘It’s crucial for us to know why they choose to do that, rather than just feeding off of the coast of New Zealand, which is much closer, and therefore they’d use a lot less energy.

‘‘We have a theory that it might be to do with the kind of prey that they’re able to find.

‘‘So being able to measure energy content could help to answer that question and start to pick it apart.’’

Researchers worked in collaboration with the Tawaki Project — a long-term study of the marine ecology, breeding biology and population dynamics of New Zealand’s crested penguins — to develop the new technique.

Otago marine sciences supervisor and Tawaki Project co-director Dr Ursula Ellenberg said she was pleased with the results.

‘‘Precise prey-size estimations from animal-borne video footage will significantly enhance our ability to study predator-prey interactions and energy dynamics in marine ecosystems.’’

Advertisement