His claims are denied by the Department of Conservation, which says the poor breeding seasons can be attributed to extreme weather events.

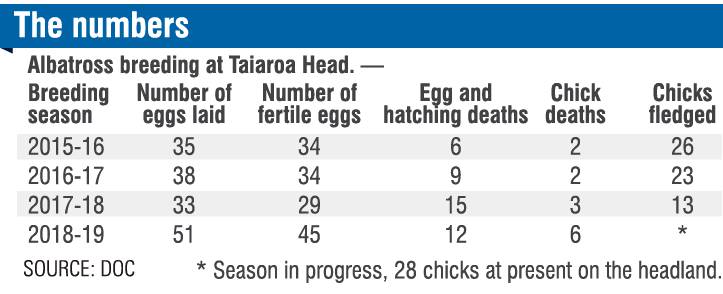

Information released to the Otago Daily Times by the department shows in the 2015-16 season chicks fledged from 74.3% of eggs laid at the Dunedin colony.

The next year it was 60.5%, last season it was 39.4% and this season, which is ongoing, it is 54.9%.

Former department head ranger of the site Lyndon Perriman said it was ''disappointing'' to hear the breeding statistics.

''I can't see how these high rates of losses are just purely environmentally caused.''

Mr Perriman began work at the colony in 1989 and left during the 2016-17 season.

He was concerned with the way it seemed to be managed.

''What I'm hearing is that there are times when there are no staff down there, which you can get away with at certain times of the year, but other times people need to be on the ground every day.''

Two seasons ago, he noticed rangers were arriving late in the morning, which meant they could miss catching bird fly-strike.

He had also noticed many ''different faces'' among the rangers. The department ran the risk of having inexperienced staff.

''I'm not trying to attack new rangers, but you can't learn that job in a season.''

He was also concerned about the possibility that rangers could be instructed to let nature take its course on some chicks and concentrate efforts on some and not others.

The idea had been raised as a possible management technique on a number of occasions over the years.

''It's very demoralising on staff to hear those comments coming from management.''

Doc coastal Otago operations manager Mike Hopkins said it was not correct that there were not staff at the colony at appropriate times.

''Skilled biodiversity rangers are rostered on site at all important times and work directly with the chicks and their parents on the headland.''

He also denied a strategy of caring for some chicks over others.

''All toroa [albatross] chicks are managed as needed to ensure that they will fledge successfully.''

The department was committed through the Pukekura reserves management plan to maximising the breeding success of the colony, he said.

There were ''varying levels of expertise'', but collectively they had more than 40 years' experience there.

Extreme weather associated with climate change was the likely cause of many of the embryo deaths. It could lead to parental abandonments and fluctuating incubation temperatures.

Albatross Centre manager Hoani Langsbury said the Otago Peninsula Trust was concerned about the hatching successes and had requested information from the department.

Climate was an influencing factor, but the trust did not know to what extent.

It had confidence in information Mr Perriman gathered about the species over his time there.

''The only difference is he hasn't been on the headland for the last two years. But asking the question is the right thing to be doing.''