As a child, Ewan Fordyce had an early interest in the natural world, which included a fascination with fossils. He was that rare person who could take a childhood interest and turn it into a distinguished academic career.

That child would have been proud to know that when he retired in 2021, as an Emeritus Professor of the University of Otago’s Department of Geology, that a 104-page tribute volume would be published in his honour by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand.

R E Fordyce: Tributes From A Global Community was a moving account of reminiscences, thanks and salutations from 62 scientists from the United States, Europe, Asia, South America, Mexico, Australia and New Zealand, which was testament to his talents as a teacher, mentor, academic and colleague, and his ground-breaking work as a researcher who brought southern hemisphere paleontology to the scientific community.

"Over the past 40 years, thanks in large part to Ewan’s contribution, Otago has had by far the most thriving teaching and research programme in paleontology in New Zealand, and arguably the best in Australasia," honorary Associate Professor Daphne Lee wrote in her introduction.

Those salutes were to a career which began when as a teenager and a member of Canterbury Museum’s Junior Club, he met PhD students needing to analyse fossils. He helped out in the weekends by cycling out to the countryside to collect specimens.

Robert Ewan Fordyce was born in Christchurch on July 14 1953, the eldest child of mechanical engineer Ian and Margaret Fordyce. He died on November 10, aged 70. His dedication to nature was forged early, through a 1957 copy of the Life magazine’s children’s science book The World We Live In — the by now much-thumbed volume remains a Fordyce family treasure.

One particular image in the book fired the child’s imagination: The Age of Reptiles, a compressed version of Rudolph Zallinger’s 34m-long mural held in the Yale Peabody Museum. It depicts dinosaurs stalking a pre-historic landscape and even in his later years, it was an artwork which continued to enrapture Prof Fordyce.

His parents owned a bach at Bealey Spur, near Arthur’s Pass, and Prof Fordyce loved to observe and explore the nearby tracks, forest, birds and the Waimakariri riverbed, forging a life-long connection to the natural landscape.

He earned the nickname "Prof" at an early age — the title was conferred for real in 2011.

Educated at Burnside High School, science was his passion. At home, the former hen house was converted into a laboratory in which Prof Fordyce carried out a range of experiments and kept various specimens of animals and insects.

His weekends were spent biking out into the countryside to hunt for fossils, good preparation for his eventual science studies at the University of Canterbury.

He graduated from the University of Canterbury with a BSC Honours in Zoology in 1974: the subject of his research was the whio/blue duck.

He continued studying at Canterbury and completed his PhD in zoology and geology in 1978, his thesis topic being "The morphology and systematics of New Zealand fossil cetacea".

Then followed postdoctoral positions at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC in 1979-80, and at Melbourne’s Monash University in 1980-81.

In 1982 Prof Fordyce accepted a position as a lecturer in geology at the University of Otago, a role he held until retirement.

At Otago Prof Fordyce taught generations of students about paleontology, sedimentology and stratigraphy, from first-years to post-grads. Prof Fordyce’s reputation soon spread and non-science students needing an additional paper often found themselves in his lectures, and developing a lasting interest in subjects they had initially had little enthusiasm for.

Prof Fordyce’s areas of expertise, enthusiasm and passion for his subject were contagious. He made regular appearances in the media, not only to explain his exciting discoveries but also to explain how these provided insight into an evolving world.

North Otago was a key field for his fossil exploration, and Prof Fordyce did much to put the Waitaki Valley on the paleontological world map, as he explained to the ODT in 2016.

"At first it was surprising, but now I know what to look for and where, and how to collect and study," he said.

"Because we have some well-preserved, well-dated, and well-documented fossils, New Zealand is a sort of Rosetta Stone to interpret the southern hemisphere history of marine backboned animals such as whales, dolphins, penguins, marine reptiles etc.

Landowners in the area were astounded to learn that their properties were once deep seabeds populated above by whales and other marine life, whose fossils were now to be found in the hills on their properties. Noting their passion and interest, he was a major contributor in developing the community-supported Vanished World Trail and Vanished World Centre in Duntroon.

Prof Fordyce’s early vision to develop the area into a Unesco GeoPark was realised in 2023, due in no small part to his powers of persuasion and enthusiasm for the project. He was proud of this achievement and that he had inspired locals to become amateur geologists. He spent decades exploring the region and promoting the treasures that lay beneath its soils.

Prof Fordyce wrote about discovering fossils that they were almost always found close to the surface, and that he had merely been the lucky person who found them before they weathered away.

Prof Fordyce explained that reading limestone terrain in search of fossils was like going to an art gallery and seeing the paintings of old masters.

"We are struck by the first impression, but when I look at the land I also examine the fine detail because to me that explains the bigger picture. Like looking at the brushstrokes the artist made."

Prof Fordyce identified more than 20 species. Once, while a student, he was fossicking near Waimate looking for whale bones when he found something completely different — a 27 million-year-old fossilised bone, only 10cm long.

Five years later it was identified as belonging to a giant penguin, now named Kairuku, which stood around 1.3m tall. The fossil remains on display in the Department of Geology Museum, and in 2014 New Zealand Post acknowledged this find by minting a commemorative Kairuku coin.

In 1987 he joined a US expedition and discovered a fossilised skull and partial skeleton of a whale on Seymour Island, off the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. That find matched an earlier discovery of part of a jaw of the same whale found by American researchers in the mid-1970s, and Prof Fordyce’s find enabled researchers to assemble a full fossil of a 34 million-year-old baleen whale, thereby slotting in an important major piece in the evolutionary jigsaw of early whales.

As well as his own discoveries, other paleontologists named several of their unique finds after him. These included kumimanu fordycei (the largest penguin to ever live, weighing about 150kg), dilophodelphis fordycei (a river dolphin), and eoscaphella fordycei (a mollusc).

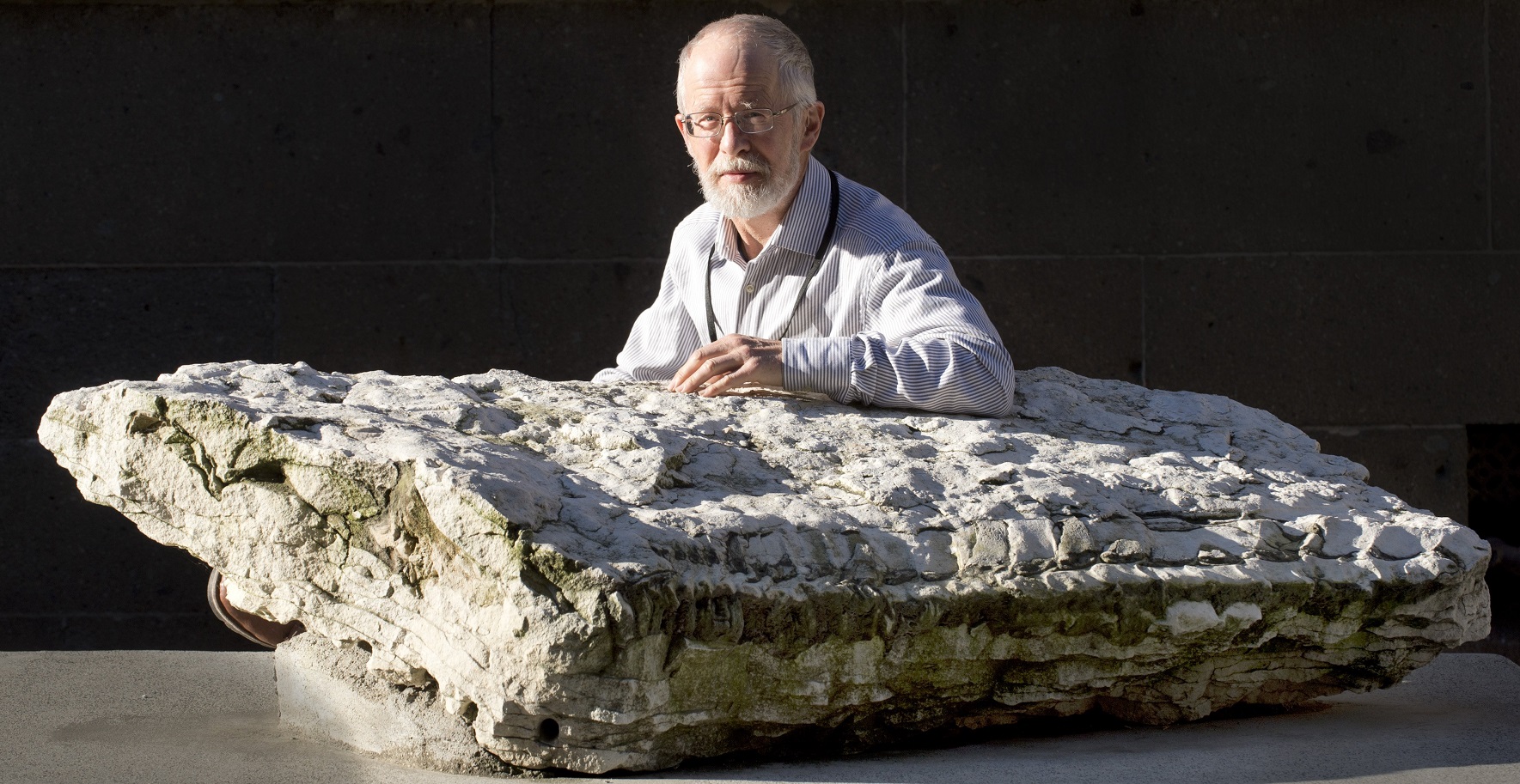

He did not keep a private collection; all Prof Fordyce’s finds are held in the University of Otago Geology Museum and collections so that others could benefit from seeing what he called "memorials to the fragility of existence".

The public can view some of the fossils in the museum, and a plesiosaur recovered from Shag Point is on loan to the Otago Museum and can be seen in the Southern Lands, Southern People gallery.

Where others referred to text books, Prof Fordyce wrote them: Google Scholar lists 211 publications, including books, chapters, more than 100 research articles and dozens of published conference papers.

That body of work meant he cemented his reputation as an internationally renowned scholar and a sought-after supervisor of doctoral and post-doctoral work. Students from every corner of the globe came to Dunedin to study at Otago. About 50 of them qualified for Otago PhD scholarships, and most have contributed to research published in the name of the university.

With academic prominence came awards. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand, a recipient of the society’s Hutton Medal, and Geoscience Society’s McKay Hammer, the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology Riversleigh medal and the Antarctic Service Medal from the US Department of the Navy.

Prof Fordyce’s prolific output continued through until retirement in 2021, as he worked on a 2019 Marsden Fund-project investigating field sites for whales and dolphins from 18-20 million years ago.

Prof Fordyce was a skilled photographer and enthusiastic tramper.

He was a keen teller of stories, particularly ones which showed that there was still much more to be explained. He shared his knowledge with kindness, and a gentle, wry sense of humour.

He married Marilyn Lloyd in Alexandra in 1976. Son Robbie was born in 1984 and daughter Anna in 1986.

Prof Fordyce is survived by Marilyn, his two children, and an enormous body of writing, photographs and finds which will educate and inspire students for generations to come.

By Mike Houlahan, with assistance from Marilyn Fordyce and drawing on a tribute by Otago science communicator Guy Frederick