Hitting a borrowing limit, but still needing to spend, is the ultimate nightmare for any organisation. That’s when things can go bump.

The University of Otago’s debt is spiralling down towards its limit for two reasons. It is spending big on new and refurbished buildings. It is also spending big on its every day running costs, which are increasingly soaring above income, causing a large budget shortfall and end-of-year miserable deficit position, despite efforts to save.

There is an even bigger shortfall expected by the end of this year. A plan in place to make even more savings to tackle the shortfall will still mean the year ends with an even bigger deficit.

"In some instances, a surplus much larger than 3% may be required to fund a sensible capital expenditure programme," it told the ODT.

At the very least, a surplus is important to mitigate inflationary cost increases the following year. Inflation alone is running at 5%.

A brakes-on strategy was announced in April by acting vice-chancellor Helen Nicholson, in a speech to staff and journalists. Things had "gone in the wrong direction at an accelerating pace". It was time to be "transparent ... about our untenable situations and the hard work starts now".

The university was spiralling down but had "a plan". There was a "need to reduce its annual operating budget by about $60 million — and salary savings will need to be a significant component". Several hundred roles would be likely affected, Prof Nicholson said. It was no surprise — more than half the university’s operating expenditure is staff.

Capital expenditure would also be slowed where possible.

The "$60m" was the budget hole last year, later updated to $61.5m, and 7% of running costs. There was an obvious question — how long to slash that much? Hard and fast cuts in 2023 and 2024 would hopefully get the job done. Doing it more slowly would risk increasingly large operating budget holes that the $60m savings would not bridge — and debt.

A third of the year had already disappeared by the time Prof Nicholson spoke up and the year was forecast to end with a disastrous $25.36m deficit and $107m in debt.

A surprising slow down of cuts is now the plan for this year’s budget — forecast to end with an even bigger $28.9m deficit forecast and $203m in debt.

It is puzzling and concerning. Chief financial officer Brian Trott says the university forecasts that in 2025 and 2026 there will be a "recovery in student numbers and we need to ensure we have the resource and capability to provide services". In other words, cuts are being slowed down to cater for a better future.

However, the projected demographic uptick in school leavers has been known about for years. Prof Nicholson had said in April "if we make no changes, then even if student numbers improve, we are looking at deficit budgets for the next several years". The message was clear — this is not OK.

Prof Nicholson has further answered, now, that there are a "raft of factors" that have changed the university’s "tactics" in recent months. She points to good news — a $10.5m bail out given by the government to help 2024’s budget, plus factors including international enrolment projections and competitive grants won.

Another answer could be internal pressure. The reaction of staff to Prof Nicholson’s original announcements was informed — and unhappy.

It had not required a professor in rocket science to work out that a 7% savings target could mean 1 in 14 jobs going — 280 of about 4000 staff. It stacked up with Prof Nicholson’s statement that "several hundred roles" would be affected.

The union objected. Marches happened. Letters were written to the university and government. The $10.5m government bail out was provided, along with a voluntary redundancy round resulting in 118 jobs going. A few more compulsory redundancies have been announced, but not many.

In September, the Protect Otago Action Group spokesman Dr Olivier Jutel made a statement similar to Mr Trott’s. There were risks to the university running "lean" because the university would need to "build" again.

However, talking to the ODT this month, Dr Jutel also flagged the obvious — curbing savings created "immense" pressure.

"If we don’t get the students, then a stiff financial wind could blow us over."

The borrowing

The university has a borrowing limit of $400m, but has an agreement with TEC not to go over $330m. It must keep a bit kept back, for an unanticipated crisis.

Borrowing is new territory for the university. It had not borrowed in living memory before December 2022 when a debt of $30m was incurred. Debt rose in 2023 to a projected end of year position of $107m and is projected to nearly double to an eye-watering $203m by the end of this year - out of which $123m is not expected to be short-term loans.

By the end of 2025, debt could be significantly higher again due to capital spending alone. Capital expenditure of $152.9m was spent in 2023 - $96.73m under-budget in part due to a slow down to save cash - but a further $178m is planned this year and $178.6m in 2025.

Some of this huge borrowing can be paid off within the operating budget, using a "depreciation" expenditure line — but the rest is going on long-term loans.

Some capital expenditure could be slowed, as it has been in 2023, but buildings in construction must be finished eventually.

The university says borrowing reduces in January when annual tuition income lands in the university’s bank account — but cash flow variances only provide temporary respite. The hefty overdraft will return within the year, only bigger, due to the continued need to borrow.

When asked by the ODT whether the university was risking knocking on the door of its borrowing limit, Prof Nicholson replied she is "comfortable this risk is being appropriately managed" and pointed to the $70m available to the university as a last resort, and the option to slow expenditure on building works.

The poorly operating budgets

The poorly operating budgets

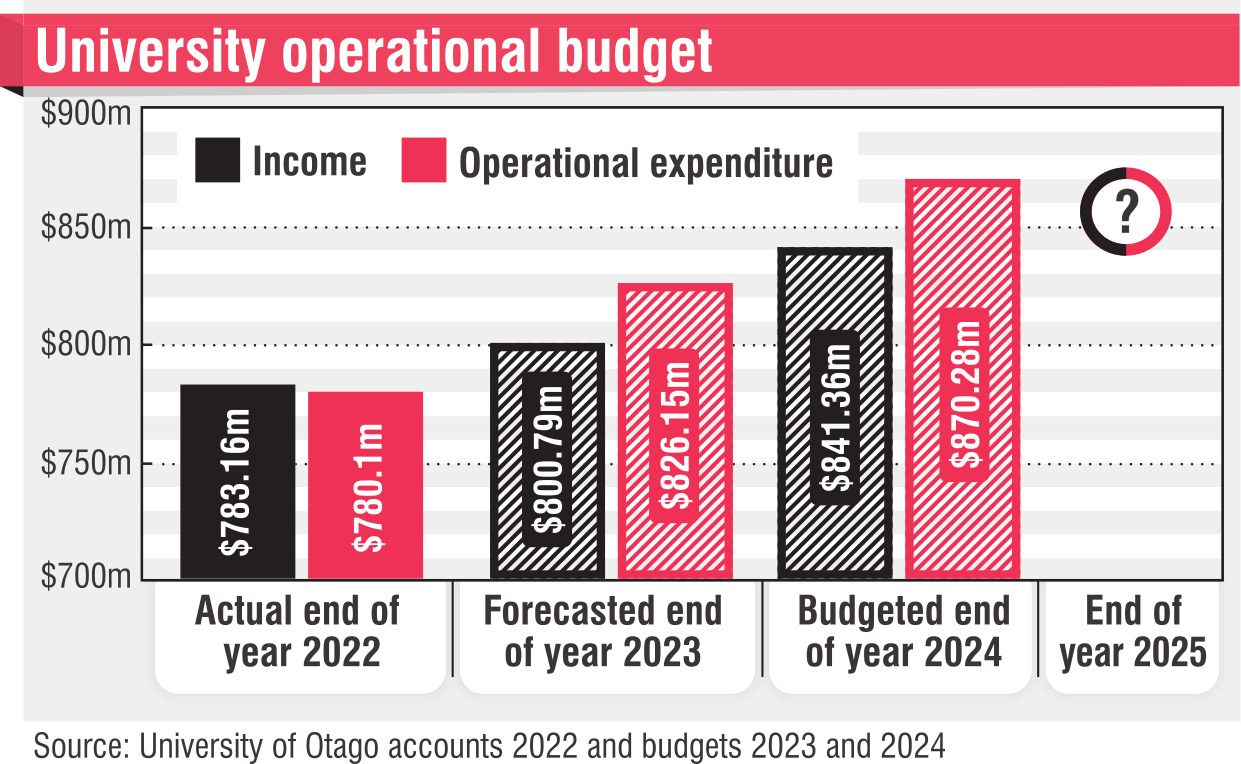

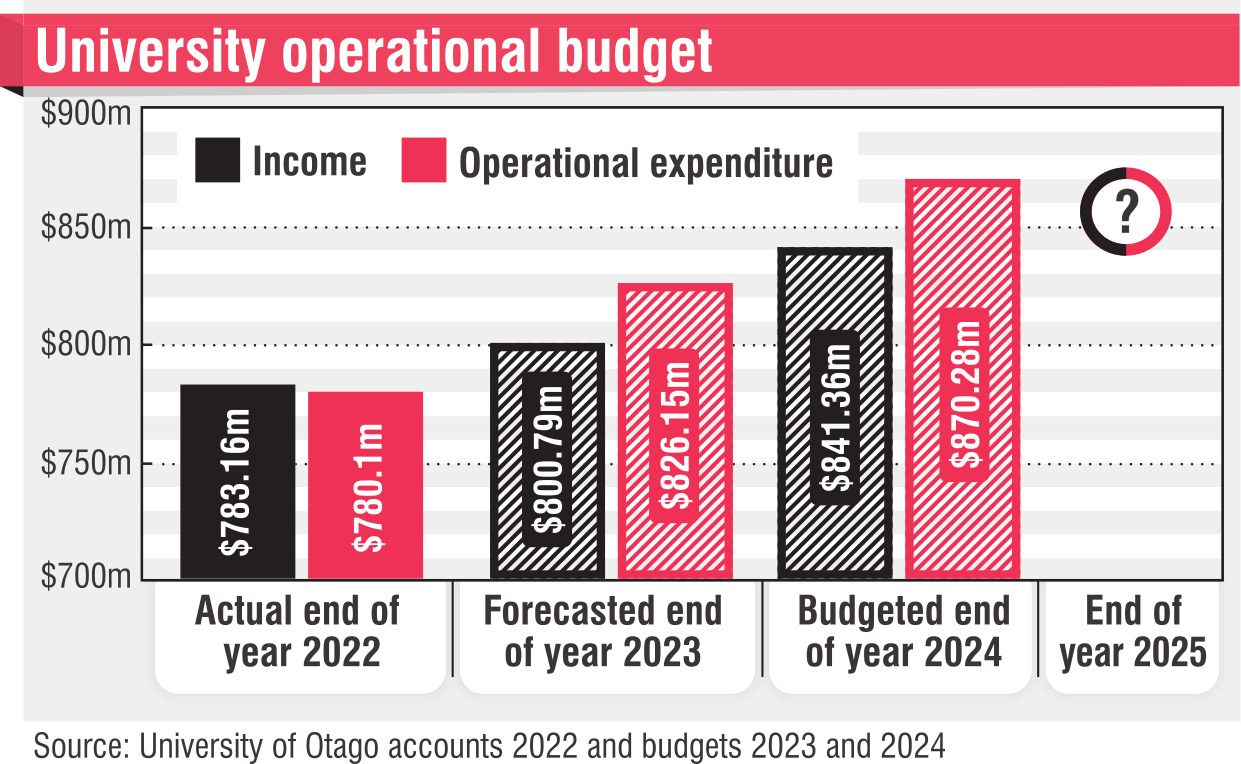

The three-year operating budget trends present a bleak picture of expenditure stretching away from income, even with savings of nearly $60m imbedded in the budgets for 2023 and 2024.

Total operational expenditure is on the rise by more than 5% a year, from $780.1m in 2022, to a forecast $826.15m in 2023, and $870.28m in 2024.

Despite the staff cuts, expenditure on salaries and related costs — more than half total expenditure — has risen from $439.3m in 2022 to a forecast $459.6m in 2023 and $475.3m in 2024. To the casual eye, these changes look like pay rises for a static workforce, not a slashed workforce.

Meanwhile, income is rising too but falling even further below expenditure, creating bigger budget holes. Income was $783.16m in 2022, was forecast at $800.78m for 2023 and $841.36m in 2024.

What happened last year?

When last year’s operating budget was being prepared in 2022, a $37m gap between expenditure and income was identified. However, fewer students rocked up than budgeted for, reducing tuition income by $24.5m and growing the gap to $61.5m.

This number was then used by the university as its goal for permanent savings.

To achieve a modest surplus would have required a further $25m, bringing the total budget hole to $86.5m to be healthy.

A $25m "savings target" — that the university chose not to mention in its budget, but that the budget was contingent on achieving — has been achieved in 2023. However, a significant chunk of these savings will not help future years’ budgets. They include a one-off $6.3m reduction in scholarship expenditure, and a further $4m saved by not filling vacant positions for a while.

A voluntary redundancy programme has cut 118 jobs, and a few compulsory redundancies have happened. However, the cost of redundancy payments was $6.5m in 2023, and the redundancies are only expected to save $9m this year.

The more important score on the door was last year’s end-of-year operating deficit — $25.36m.

What is planned for this year?

The plan for this year is to keep incurring operating expenditure above, and rising faster than income. The budget hole is consequently growing, not closing.

There is a budget hole of $63.57m. The current plan is to make $34.67m savings and end the year with a whopping deficit of $28.9m.

The budget hole would have been bigger still — more than $74m, or nearly $100m to turn the level of surplus required by the TEC — if the $10.5m government bail out hadn’t happened.

The $34.67m savings includes $17.47m asset sales and a $17.2m "savings target". Similarly to 2023, a significant chunk — at least slightly over half — of these savings will not help future years’ budgets. Assets, for example, cannot be sold twice.

The university has said previously anticipated job cuts will be curbed. Finance chief Mr Trott says "some areas of the university will likely work through management of change processes in 2024, but at this stage we do not anticipate the need for a further general round of redundancies". Some salary savings will however be achieved through "non-renewal of a number of fixed term positions and through leaving a number of vacant permanent positions unfilled".

.. And in 2025?

The university says it will have achieved a permanent saving of $60m within its 2025 budget. The savings’ components are not entirely possible to determine, because the nearly $60m savings planned for 2023 and 2024, and another $20.3m savings provisionally set for 2025, include significant permanent savings and one-off savings that don’t benefit future years.

Regardless, the bigger question is whether permanent savings achieved, combined with hoped-for income recovery, is enough to raise income to match and then quickly exceed expenditure, and stop and reverse the slide to the bottom.

The budget for 2025 won’t be available until the tail-end of this year. The university hopes to break even, and then turn a surplus in 2026. How this will be achieved, however, is unclear.

If operational expenditure carries on going up at its current forecast rate of above 5%, more than $46m extra funds would need to be found in 2025, compared with 2024, just to cover this additional cost.

Less than half of this amount — about $22m — is hoped to be achieved from an increase in students next year. Additional medical places have been confirmed for this year and strongly signalled for 2025, Prof Nicholson says.

Mr Trott says there is continued scope to "trim" the university’s planned capital expenditure to hold back the debt slide if the situation is "worse than we are forecasting" — or, conversely, accelerate it if things are better.

The students better come flocking.

Advertisement