However, "where" is a question left unaddressed by the legislation New Zealanders will vote on in the October 17 referendum.

Unlike other major life events, death is one where people may not have a choice of venue due to medical requirements - and given the strict regime of requirements which will be in place should New Zealand vote "Yes", people may very likely be in hospital, or hospital-level care in an aged-care facility.

Clinicians are able to exercise their conscience and opt not to provide assisted dying services, but Parliament explicitly chose not to offer the same option to the facilities and services which employ them.

Dunedin-based National list MP Michael Woodhouse - himself a former hospital administrator - proposed an amendment to the Bill which offered facilities the right of conscientious objection.

As Mr Woodhouse was overseas, Dunedin North MP and at the time Health Minister David Clark proposed the amendment, pointing out that many care providers and hospitals had a religious background and doctrinal opposition to assisted dying.

The issue did not go away though, and Hospice New Zealand - which opposed the Act - went to court to ask for a declaratory judgement as to the effect of various clauses of the End Of Life Choice Act.

In June, Justice Jill Mallon - after long consideration as to whether the court even had jurisdiction to consider a law which had yet to come into effect - decided she could not grant Hospice NZ the declarations it sought.

Instead, she offered an interpretation of what the statute said, and in doing so effectively gave the organisation what it was looking for: a declaratory statement that it could conscientiously object.

"The End of Life Choice Act does not require hospices or other organisations to provide assisted dying services," she said.

"They are entitled to choose not to provide these services. This does not depend on a hospice or other organisation having a conscientious objection, although that may often be the reason, and allowing hospices or other organisations not to offer assisted dying services is consistent with the right to freedom of conscience under section 13 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act."

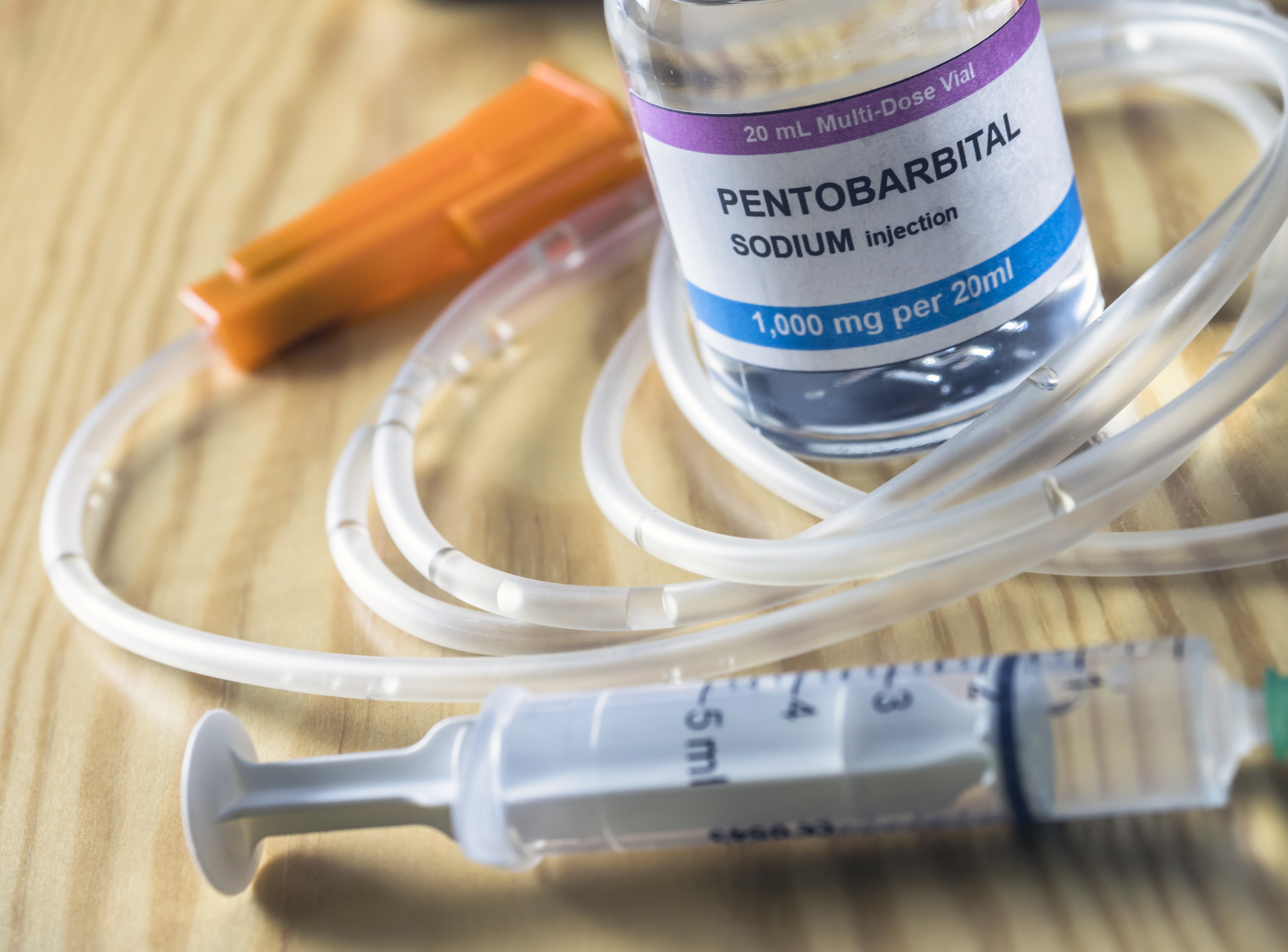

"We will continue to support all our patients and families using the principles of excellent palliative care, but our staff will not assess eligibility for assisted dying, nor deliver or be present during the administration of lethal doses of medication," chief executive Ginny Green said.

"Furthermore, these medications cannot be administered by anyone on any of our premises."

However, Otago Community Hospice respected individual choice and if it was providing palliative care to someone who had opted to avail themselves of assisted dying it would continue to do so, Ms Green said.

"We will respect a patient’s decision should they choose the option of assisted dying and continue to provide the same compassionate care as we would any patient referred to our service.

"This is a very complex situation and we all need to be prepared as to how each of us will move forward if the referendum goes through."

While Hospice is now satisfied as an organisation it does not need to provide euthanasia services, questions remain for other institutions - particularly public and publicly-funded bodies.

The Act provides that a 12-month period elapse before it comes into force and, as Justice Mallon noted, the Ministry of Health has yet to consider funding and procurement of assisted dying services - or indeed if assisted dying services will be funded at all.

"If assisted dying services fall within the ambit of district health boards, they will make provision and funding decisions in accordance with the statutory framework and government policies under which it operates," she said.

The Southern DHB chose not to comment for this article, saying as a state agency and with the issue subject to a referendum it was not appropriate to do so.

Provision of all health services in the SDHB - the largest DHB by area in New Zealand - is always an issue, and with the option for clinicians to conscientiously object, some rural areas in the region may well battle to provide assisted dying should the referendum pass.

Some, but not all, rural hospitals are run by DHBs and will follow their policies.

"The hospital would have to establish a referral system, which is no different from most services that are not performed by every individual or by every site."

Mr Anton suspected euthanasia could become like several specialist services not provided for in regional areas, and patients would have to travel to access it.

"It is also possible that there may be roving clinicians who are qualified and accredited to provide end of life services in smaller regions," he said.

"It should be noted that these patients may receive their end of life care in the community and not in a hospital setting."

The big question remains: could a DHB refuse to offer assisted dying?

Otago law and bioethics lecturer Jeanne Snelling suspects the answer would be yes, although it was less likely a board would succeed with the same "contrary to its ethos" argument used by Hospice NZ.

"Where it gets pretty murky for me is where a healthcare provider does not have a conscientious objection - and is employed by an organisation that is exercising a conscientious objection," Dr Snelling said.

"It seems to suggest that it is left open whether they could provide the service if they were providing care outside of the organisation, but then seems to say that they may be able to provide assisted dying even within the organisation if there was an agreement between the provider and the organisation.

"What it suggests to me is that in that case it may be treated as an employment issue."

It also suggests that the Hospice NZ case is far from the first assisted dying case the courts might see, should New Zealand vote yes on October 17.

Your thoughts