Seventy years ago the caves that gave Te Anau its name were rediscovered by two entrepreneurs who turned them into one of the town’s greatest tourist attractions. Alina Suchanski tells the story.

Wilson Cameron Campbell and his friend Lawson Burrows shared a passion for and fascination with Fiordland long before they came to live in Te Anau.

In the 1930s they would travel every Friday on the gravel road that joined Gore with Te Anau to spend the weekend among the magnificent scenery of mountains, lakes and fiords.

When World War 2 started, both men were conscripted to the RNZAF, and when they returned to New Zealand at the war's end they started a business partnership that lasted 26 years. In 1947 they bought a 30ft launch, the Quintin MacKinnon, to run scenic trips on Lake Te Anau.

This was the start of Fiordland Travels. Lawson gave up his job in Gore and moved to Te Anau to run the business, while Wilson continued to live and work in Gore, and commuted every weekend to help.

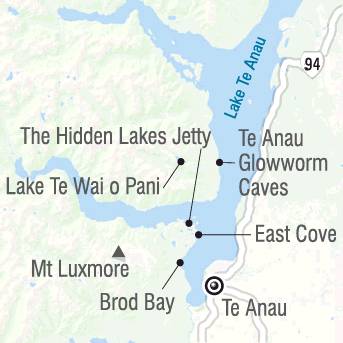

Over the next few years they built jetties around Lake Te Anau and took visitors to the Hidden Lakes near the entrance to the South Fiord. Accessible only by a boat trip across Lake Te Anau, followed by a short bushwalk, the Hidden Lakes can be seen from the air or from Mt Luxmore.

Fiordland Travels had a boat on Lake Te Wai o Pani for exploring the secluded lake with their guests, fittingly named The Explorer.

Campbell and Burrows had often wondered about the meaning of "Te Anau''. They heard different stories, but one that caught their imagination was that it could be a corruption of the Maori "Te Ana-au'', meaning a cave with swirling water.

However, even the oldest residents of Te Anau did not know of any such caves. Undeterred, the two men began searching for a cave on their many trips around the lake.

In his book Te Anau Anchorage, Burrows describes how in May 1948 he found a stream (now called the Tunnel Burn) flowing out of a cave in the Murchison Mountains, but its opening was too low to enter.

Excited with his discovery, Burrows came back with Campbell and another friend, Milford Track guide George Pollard, to further explore the cave with the use of lamps, ropes and ladders. Inside they found a waterfall pouring over a vertical cliff.

Climbing up the side of the waterfall and continuing into the cave they stumbled upon a large grotto with walls and ceiling illuminated by millions of glowworms, reflecting in a 12m-wide pool of water underneath.

Campbell and Burrows worked hard to develop the caves as a commercial venture in order to show this amazing discovery to tourists. Their first challenge was to improve access to the cave.

Initially, visitors had to climb down a rope to the cave entrance and slide inside lying on a board. Later the two men found a trench, overgrown and full of rocks, that could be used as an access point.

Once it was cleared and a footpath built, they contracted the Public Works Department to blast the entrance and raise it by about 60cm. It was still necessary to stoop to get in, but most people could manage it.

Continuing the improvements, they dammed the lower part of the cave and put a flat-bottom boat on the stream to take tourists to the waterfall. They installed a ladder up the waterfall, built walkways and bridges, and put electric lights in the cave. Outside, they built a bridge over the Tunnel Burn and a jetty for the boats bringing tourists from Te Anau.

After the discovery of the glowworm caves, Campbell and Burrows abandoned their trips to the Hidden Lakes and focused entirely on the caves.

Legend had it that the original boat the two men used on Lake Te Wai o Pani was still on the shore. Having learned about the Campbell and Burrows ventures and adventures, I felt compelled to go to the Hidden Lakes and look for the old boat. And so one sunny morning I launched my kayak on Lake Te Anau and set out on what had turned out to be an adventure of my own.

After paddling across to Brod Bay I followed the shore for about an hour to East Cove, where Campbell and Burrows used to take their passengers. A bunch of manuka logs sticks out of the water still, the only remnant of a jetty they built 70 years ago.

The track they cut in the bush, now managed by the Department of Conservation, connects East Cove with the Hidden Lakes wharf and goes past two of the little lakes. I paddled on past the Dome Islands to the wharf, where I dragged my kayak on to the beach and followed the track on foot.

From the wharf it only takes 10 minutes to reach Lake Te Wai o Pani. Once there, I left the marked track and bush-bashed my way along its shoreline looking for remnants of The Explorer. It was easy hiking through sparse ribbonwood forest and what looked like remains of an old walking trail. Half an hour later, I suddenly saw it. Only the bow of the boat was sticking above the ground, the rest buried in earth and rotting leaves.

Having achieved my goal I pondered what to do next, turn back or continue my exploration. I decided to carry on and the going was still easy until a vertical rock wall stopped me in my tracks.

There were only two things I could do; walk around it or climb over it. I chose the latter and found a flat platform on top of the cliff with a splendid view of the lake I was in the process of circumnavigating.

After lunch at this scenic spot I carried on, keeping close to the lake edge for fear of getting lost in the bush. To my relief, I came across a track with DOC markers that led me back to the wharf where I had left my kayak.

Following the discovery of the caves, Fiordland Travels continued to prosper until in 1965 when Les Hutchins purchased the business, merging it with his Manapouri Doubtful Sound Tourist Company to form Real Journeys, now the largest family-owned travel company in New Zealand.

Today, two independent operators continue the legacy of Fiordland Travels by taking tourists to the Hidden Lakes. The glowworm caves are a major tourist attraction in Te Anau, visited by hundreds each day.

Everyone entering the cave must bow to the gods of the underground. By doing so they also bow to the men who put countless hours of back-breaking labour into making the caves accessible to people of all ages, fitness levels and nationalities for decades to come.