A bright yellow bag laden with supplies, including torch, toilet roll and cat food, sits ready by the door of Emma Kate Lamb's family home. Every month or so, documents and precious photos are copied and stored on a hard drive and returned to the emergency kit.

Lamb, her husband and their two young daughters will be prepared for the next big flood event to hit Young St, St Kilda, in South Dunedin.

On June 3, 2015, it happened. Within the space of 24 hours, 175mm of rain fell, drenching the area. It was the biggest single rainfall event since 1923. In this low-lying area, already vulnerable to ponding, the systems in place were unable to cope. Water flooded streets, gardens, homes and workplaces.

"When it happened, I had actually just become pregnant," says Lamb. "I had a really yucky pregnancy and I remember being really crook. But I was also thinking `Oh my goodness, how much water can we get? Will it come up towards the doors or will we be good?' In the end we were good."

Their garden was flooded, but not the house. Others close by were less fortunate.

According to the Dunedin City Council, about 1250 properties across the city were affected that night, most of them in South Dunedin. Some families had to evacuate. Some did not get back into their homes for weeks.

Next morning, armed with food, Lamb went down to a nearby emergency post, hoping to donate to other residents whose homes were sodden. "Strangely," she says, "there was almost no-one at the emergency post."

Instead, residents were still busy battling water entering their homes, this time caused by curious onlookers in their cars. "Every time a car went past, a bow wave would go into a property."

Spurred to action, Lamb initiated contact with her community, in part to get to know people, but also because she realised that South Dunedin could not be resilient in the face of another event without a better connected community.

In another part of greater South Dunedin, Eleanor Doig lives in the "dippiest bit" of Musselburgh. Like Lamb, she experienced extensive flooding to her garden. "We had mid-calf water out to the end of the section."

In 2016, Doig attended a meeting for South Dunedin "stakeholders" held by the Dunedin City Council.

"They were all dressed up posh and I went along in my T-shirt and shorts!" she says, laughing. "That was an amazing group because people started realising that there are a lot of people working in South Dunedin and they started learning what everyone was doing. And they started to get this quite strong South Dunedin network."

With Doig, the group has gone on to hold a number of events aimed at connecting people in the community. One last month attracted a crowd of 50. Led by Doig and Mike Tonks, the theme was "Water and Climate Change", and involved presentations by DCC staff.

South Dunedin's challenges have also attracted the attention of outside groups concerned about the effects of climate change on vulnerable communities. In March, the Blueskin Resilient Communities Trust, along with the Deep South National Challenge, held a meeting in South Dunedin focused on issues around community-driven climate change adaptation.

Like South Dunedin, Blueskin Bay is home to low-lying coastal communities, albeit on a much smaller scale.

Principal co-ordinator Scott Willis, from BRCT, said people at the South Dunedin meeting listened to presentations, shared and brainstormed together.

"The importance of community was repeated again and again and again," he says.

The area has attracted people with limited mobility because of its flat topography, support services, good access to shops and relatively low house prices.

With this in mind, "we hope to have a Wheels Day in January 2019," says Doig. "Wheel chairs, motorised scooters, walkers and kids' skateboards; wheels of any sort."

Significant physical as well as social factors vex South Dunedin.

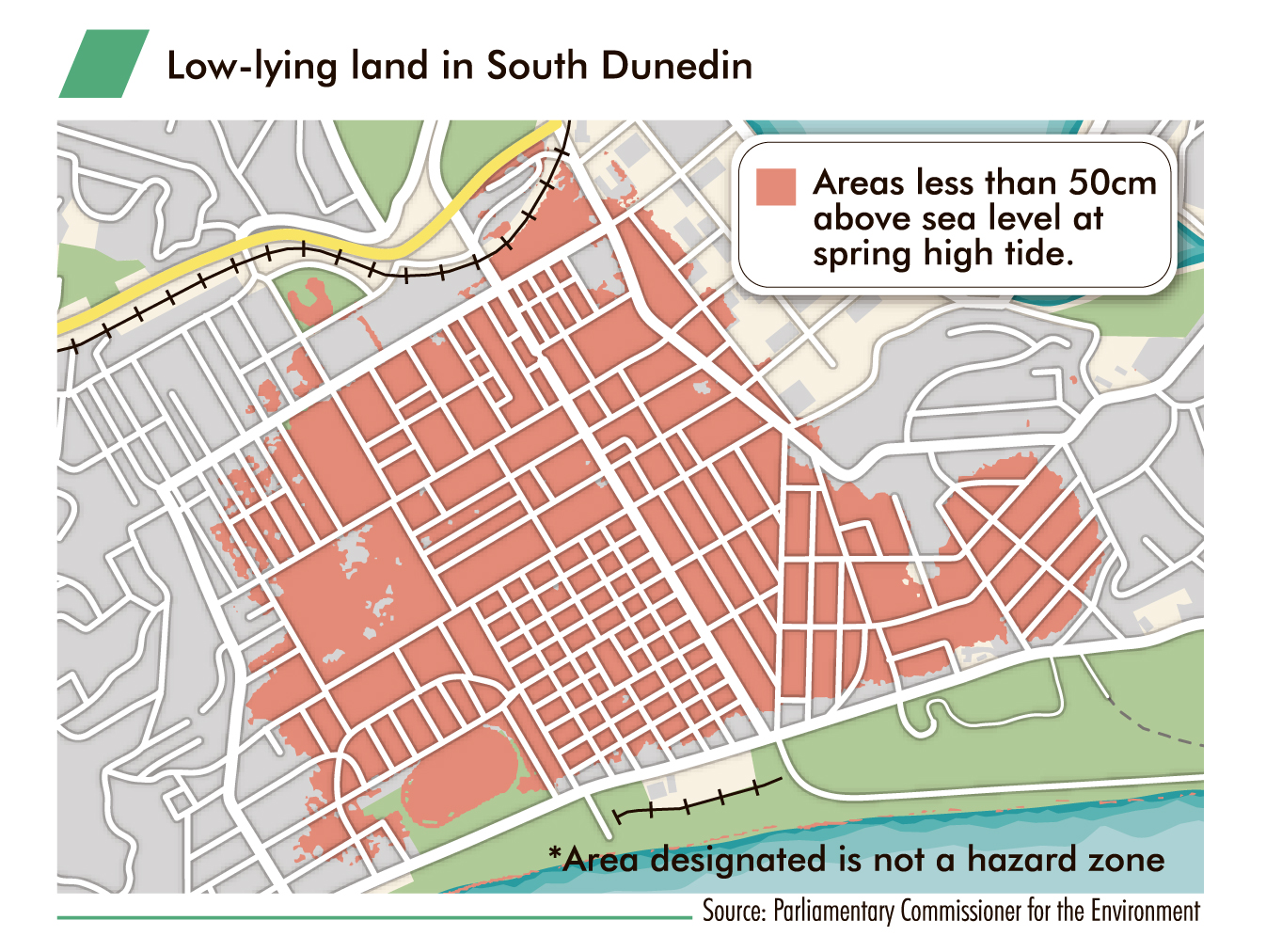

In April 2016, Dr Jan Wright, then Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, called South Dunedin the "most troubling example" of high groundwater levels in the country.

Some of the low-lying 600ha area sits on land that was once dune, wetland and saltwater marshland. It was called Kaituna, as it was a traditional eel harvesting site for Maori. Reclamation by European settlers began from the mid 1800s, slowly turning the natural wetland into the densely housed population of about 10,000 residents today.

Other factors that predispose the area to flooding include the poorly consolidated underlying sediment that appears to be sinking in some places, a shallow water table that is both connected to the nearby ocean and to groundwater, and to Dunedin attracting increasingly extreme rainfall events.

Interestingly, a study of a multi-layered database of superimposed maps of greater South Dunedin indicates that the most flood-prone areas are not those closest to sea-level (St Kilda east) but the slightly higher areas of Forbury and St Kilda west.

That work was supervised by Assoc Prof Janet Stephenson, director of the Centre for Sustainability at the University of Otago.

"There is still a lot that is not known about how sea-level rise will affect South Dunedin," she says. "There is still quite a lot of basic science to be done."

In a South Dunedin Update leaflet drop to households this past winter, the DCC shared nine initiatives since 2015 that address and should mitigate future flooding. These include a new, larger $300,000 filter screen at the Portobello Rd stormwater pumping station, as well as improved maintenance and inspection of the mud tanks that lie across the area.

More work is planned, with about $90 million of improvements to wastewater management and flood reduction in the pipeline.

The council's "South Dunedin's Future" strategy focuses on the medium and longer term implications of sea-level rise on the area, says corporate policy manager Maria Ioannou. A projection of 100 years is now required by central government, so that " if we can't always protect South Dunedin, what are our other options".

The council is especially interested in "opportunities for resolving more long-term intractable issues in the area", Ioannou says.

One of the options being investigated by Tom Dyer, manager of the DCC's 3 Waters Group, is the creation of a stream through the area that could channel water out to sea. Some poor housing stock could be removed, providing a place for recreation and biodiversity in the form of a riparian wetland.

"We're doing the work to build some quite thought-through options that the community can then have real input on," says Ioannou.

"We can't say what the sea-level rise will be in 2040 but we can estimate what kinds of things will happen with a certain level of sea-level rise," she says.

Dunedin has also recently been identified by the Government as a medium growth city.

"When you look at growth you would also at some point be including people that need to relocate in the city, so it changes our growth conversation."

In an effort to draw in expertise and build collaborative processes, the DCC is talking with local stakeholders, with a technical advisory group, with community leaders, including Ngai Tahu, and with an academic reference group.

Stephenson is part of the academic group.

"I can certainly say there is a lot of discussion and there appears to be much more cohesion in how to work together around the adaptation question," she says.

Ioannou estimates that by March 2019, the council will have started informed multi-year conversations with the residents of South Dunedin about the impacts of climate change. She is seeking an inclusive, reciprocal approach "to give as many people as possible a voice on these issues".

"We need to go to them and talk to them in ways that work for them.

"I genuinely believe the council, or central government, won't have all the answers, we actually need to work with everyone in the room."

As the community of South Dunedin takes positive steps forward, Stephenson is also alert to the inequities that climate change could bring to an already vulnerable community. In a "Communities and Climate Change" report of which she is lead author, she cites four "maladaptive processes" that can occur when adaptation is not managed well or equitably.

These are: enclosure, for example, where public assets are transferred into private hands; exclusion, where some stakeholders are excluded from decision making; encroachment, when adaptation interventions encroach on protected natural habitat; and entrenchment, where adaptation worsens the inequities faced by already disadvantaged groups.

Doig is aware of the risks.

"That is my passion," she says. "It's my belief that if we don't develop an articulate, credible voice then this community could get walked all over in the future in terms of being most at risk around climate change, and I'm determined that won't happen."

In August, Stephenson attended the Society of Local Government Managers symposium on climate change adaptation.

"Councils do seem to be looking to Dunedin as a council at the forefront of this kind of challenge, so there is a lot of interest in how Dunedin city is managing this long-term transition."

Moving forwards, community groups such as the informal community hui group to which Doig belongs, are looking outwards for inspiration, communicating with other groups in the city including those in Northeast Valley and Green Island. They hope to work with Inspiring Communities, an organisation that catalyses locally based change.

"You do need some external input I think," says Doig.

Lamb and Doig agree that help will be needed to bring residents together. They are delighted that an application for money from the council's Place-based Community Grants Fund, and other sources, for a paid greater South Dunedin community worker was successful earlier this month. Some of the funding received will be used to set up a working office space.

At the Deep South Challenge meeting facilitated by BRCT, "people consistently said we want more discussion, we want more involvement in our future," says Willis.

"Everyone wants rolling workshops to normalise the adaptation response and to make the decisions not socially problematic.

"People also really wanted stuff to happen now."

Much can, and is, being done now, but over the longer term, the effects of climate change on sea-level rise will make low-lying areas like South Dunedin challenging for human habitation. In addition, for every degree of increase in global temperature, models show that 7% more water is held in a more volatile atmosphere prone to producing more extreme weather events.

Central government, local government, place-based services and connected communities are all essential in adapting to climate change. But when the next major event happens we all need to take some personal responsibility and action to look after ourselves, our families and for our immediate neighbours, advises Paul Allen, from Dunedin's Civil Defence Emergency Management (CDEM) group.

There are things that can be done now to prepare. Like making up an emergency kit, keeping some supplies of food and water, as well as getting to know the people who live around you, especially those who may need extra care on your street, says Allen.

"We have put in a sump and a pump, and our garden is now all in raised beds," says Doig. "One of my things is to get people planting thirsty plants, plants that will suck up some of the moisture around. We are growing an orchard in our backyard. We'll end up with probably 10 trees."

Council place-based community adviser for South Dunedin, Nick Orbell, believes the community is already very resilient.

"It's often probably held at a household level. People have had to respond to all sorts of really challenging circumstances. It has become a really resilient community, but not necessarily seeing themselves as well connected and working well together for common goals."

"Sometimes the people who are most deprived are quite resilient," says Willis, from BRCT.

"South Dunedin could be the place where we successfully manage adaptation and have an exciting outcome of creative solutions."