Neville Peat did not stand again at the last local government elections. He’d completed a term on the Dunedin City Council, but there was something else on his mind.

During his term, South Dunedin was drenched by 175mm of rain in 24 hours. It was called a one-in-100-year event. The rain could not drain quickly enough, as coastal South Dunedin is about as low as you can go. It is only just above sea level. There was a flood.

The suburb is an extreme example, but it shares a low-lying coastal geography with much of built New Zealand. And that’s what Peat was thinking about. The author and journalist has spent much of his life on the sea or writing about it, and knew more needed to be said.

"From my background in local government, my interest in the sea and what was happening at the edges, I thought vulnerable coastal communities, if not all of us, deserved to know more about the issues," he says.

So instead of standing again for council, Peat set about telling the story of the battle lines along our coast. The book he has written is called The Invading Sea: Coastal hazards and climate change in Aotearoa New Zealand.

"The book is both a call to action and a line in the sand — so to speak — about what we know about coastal hazards and what can be done to get prepared for worse to come," he says.

The stakes are high, Peat says, socially and economically.

Those big numbers are about real people, and their property, at risk of displacement by inundation through this century if the 1m of sea-level rise in climate scientists’ predictions comes to pass.

"A one-metre rise would affect 3300 homes in Dunedin, 3600 homes in Christchurch, 3000 homes in Napier and 2000 homes in Wellington," Peat says.

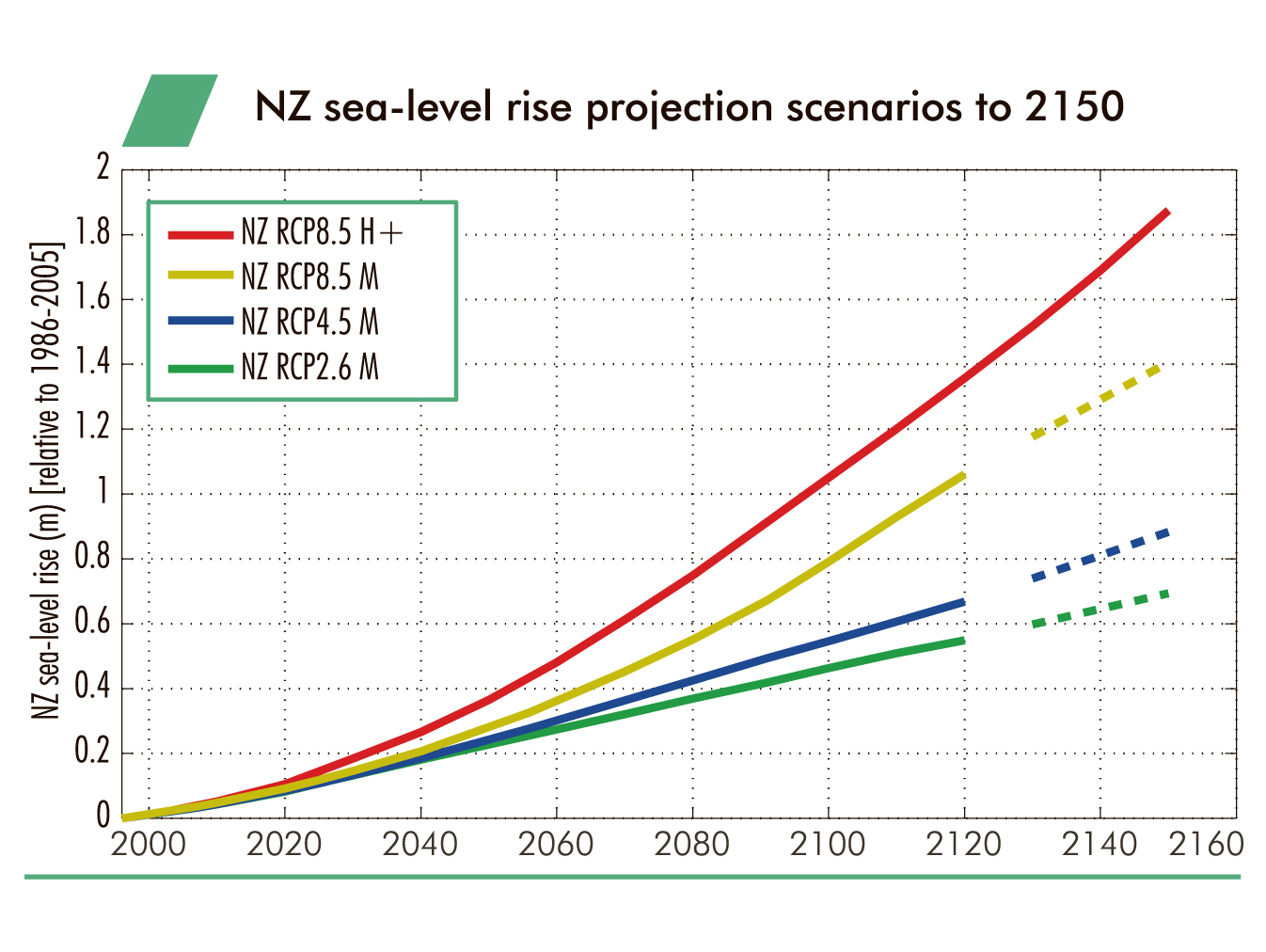

"Auckland and Christchurch councils, for example, are already planning for sea-level rise of one metre by early next century. By 2050, little more than 30 years from now, the sea could rise by up to 40cm. We need to get ready for this ‘locked-in’ rising sea."

It is a "creeping tsunami", he says.

Sea-level rise may amount to a barely perceptible 3mm a year at the moment, but when you factor in the impact of warmer, more tempestuous oceans and the accompanying storm surges, the risks for low-lying areas are compounded, he says.

"The longer we delay planning for sea-level rise and storm surges, the worse the implications and costs for future generations."

The sea rose about 20cm last century, Peat explains. Significantly, the rate of rise increased towards the end of the century as a result of ocean warming and the melting of permanent ice from the likes of Greenland and the Antarctic. What this means is that the battle has begun, and for The Invading Sea, Peat investigated the coastal communities already trying to hold back the tide.

"During field research I wasn’t surprised to see how high-profile coastal communities — for example, Mokau [in South Waikato], Buller district, North Otago, and Haumoana/Clifton in Hawke’s Bay — were having to cope with metres of erosion and flooding in some cases.

"What impressed me was the determination of coastal people, with sleeves-rolled-up resilience, to confront both angry seas and their local councils."

There are lots of places around the country where erosion has been swift and extensive: 40m lost at Sunset Beach, Port Waikato; 20m in places on the Kapiti Coast; 80m at Waitaki Boys; 80m at Carters Beach on the West Coast. Peat says there will be many more in the future.

"Coastal scientists estimate as much as 80% of New Zealand’s ocean coastline, of which we have some 11,000km, is experiencing erosion."

The evidence of Peat’s book indicates mixed success in holding that erosion at bay. But at least the country has some experience of trying. Where authorities are less well versed, is on the delicate business of managed retreat."Ultimately, in the most vulnerable places, defence will become unaffordable," Peat says.

"A certain amount of ‘accommodation’ can work, such as ponding areas to take up groundwater encroachment. Hard, engineered defences may cope with a rising sea for some decades but, if even conservative projections for sea-level rise eventuate, there will have to be retreat for some areas."

And district and city councils, Peat says, are poorly placed to deal with the retreat option.

"Councils, operating under their individually developed planning regimes with different levels of ratepayer funding and expertise, require more direction from central government. In Britain, adaptation to coastal erosion is a central government responsibility, and the UK is much better organised to deal with coastal crisis points. In New Zealand, regrettably, the Government has left it to councils to use their own discretion according to what they can afford."

Of course, it is not just buildings that will need to retreat. Infrastructure such as water pipelines, sewerage pipes and power lines will also be affected. Such considerations come into sharpest relief in places like South Dunedin.

Around New Zealand’s coast, there’s nothing quite like the Dunedin area, Peat says.

"Much of the built-up area — including three-quarters of the 2700 dwellings — lies within half a metre of high tide. Having seen a lot of urban coastal areas around the country, I reckon South Dunedin deserves to be a pilot case for a government/council joint adaptation project. In 2015, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment described South Dunedin as ‘the most troubling example’ of how groundwater can threaten a coastal community."

The interaction between affected coastal communities and local authorities has not always gone smoothly, suggesting an early start is a good idea.

The Invading Sea describes the Kapiti Coast experience, where attempts by the local council to draw lines on maps setting out the threat of erosion and inundation saw landowners push back, go to court and force a council retreat.

Peat says the lesson is that councils need to work harder on community consultation and on explaining the importance of building restrictions in areas vulnerable to sea-level rise.So what is missing in terms of the national approach to his issue? What needs to be done to prepare for what shapes as an inevitability?

Peat says previous governments have ignored requests from Local Government New Zealand to invest in a thorough analysis of coastal hazards and the level of risk and responsibility, including who is going to pay for it all.

The Government needs to front up, he says, after being remiss in the areas of climate-change mitigation and adaptation.

"It has been too easy for politicians in recent years to ignore or pay token attention to the issue of climate change and how to adapt to it."

There are some promising signs the new coalition government will be more active, but it will take some time to play out, he says.

"Measures to curb greenhouse gas emissions have not worked, and New Zealand is far from prepared to deal with an invading sea."

Among measures Peat would like to see considered is something like an Earthquake Commission for coastal erosion and flooding.

"At the very least we should have a national strategy for helping out coastal residents who’ve lived a long time by the sea and, through no fault of their own, find themselves having to retreat. Coastal erosion and flooding are natural hazards, even if human-induced," he says.

On the more proactive side of the ledger, is a government-funded National Science Challenge, Living on the Edge, Peat says. It’s a positive initiative to ensure adaptation planning looks at all the issues, he says. Hawke’s Bay is taking a lead there.

The over-riding message from The Invading Sea, is that the rest of the country needs to do likewise, and soon.

"Sea-level rise and increased storminess are predicted for the rest of this century and the next, so coastal erosion and flooding are long-term problems," Peat says.

Decisions and actions are required right now, he writes in the concluding chapter of the book.

"After all, no-one wants to face hell and high water."

The book

The Invading Sea by Neville Peat is published by The Cuba Press and will be launched in Dunedin by Sir Alan Mark at Dunedin City Library, on Wednesday at 5.30pm. RSVP by email library@dcc.govt.nz.