"Collecting faeces is not something everyone would do," University of Otago PhD candidate Mel Young admits. But she does.

Young has been probing the dung of yellow-eyed penguins (hoiho) breeding in Otago for answers about their diet.

Young's devotion to hoiho goes well beyond picking up poos, reaching back 16 years to when she first began working as a trainee ranger with the Department of Conservation.

At age 23 she worked with the birds, one of which was a year older than herself.

"She'd had 30 chicks and five mates. It just gives you that perspective as a young person."

Now a mature student, outdoorsy Young is bent over books writing up the results of her thesis. But when she was collecting data she lived a crepuscular existence, rising early to visit remote hoiho breeding areas before they left for a long day of summer foraging at sea, and visiting again when they returned ashore at dusk.

Collaborating with veterinary scientists, Young collected some of her faecal samples directly from birds, but most were scraped off the ground after adults had swum to sea.

She wanted to find out if this "passive" approach produced DNA information about their diet that was as reliable as that given by fresh samples. Happily it did, perhaps due to the vegetated nesting habitat that protects the secretive penguins' faeces from the elements, or their pellet shape, she thinks.

"They have a firmer consistency that means they've got a smaller surface area to volume ratio," she says of the hoiho poo.

"The DNA was probably in better condition because of that."

The research indicates hoiho have switched prey. When hoiho diets were first studied in the 1980s, birds were largely feasting on small oily fish species. Blue cod, a fish very low in oil, was taken but not as often.

Close to 30 years later, Young's data reveals the change.

"Two-thirds of what we found was blue cod, and it was in 100% of the samples."

Recently, at certain times, hoiho have struggled to find food. Last season across two separate starvation events, more than 400 birds out of an estimated mainland population of 700-800 birds were rehabilitated and released.

Young suspects that hoiho have been showing periodic signs of starvation for the past five to six years.

"They've probably been malnourished for a lot longer."

The switch from a balanced diet of six or seven prey types to one dominated by blue cod is problematic.

"That can result in the birds just not doing well," she explains.

It affects reproduction, overall survival and resilience to disease.

Starvation events are one of many factors impacting on New Zealand's nationally endangered penguin. On the mainland, breeding pairs have fallen since the 1990s from about 600 pairs to just 225 pairs this year, according to the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust (YEPT). Endemic to New Zealand's waters, hoiho live in two populations; the northern population that extends from North Otago to the Catlins, and includes Rakiura and Whenua Hou, and the remote southern population that breeds on sub-Antarctic islands.

Hoiho are one of 86 species of seabird breeding in New Zealand waters out of just 360 seabird species globally. It's a figure that allows us to call ourselves the world's seabird capital. Yet 90% of the seabirds that live or visit New Zealand are at risk of extinction, according to the Ministry for the Environment.

"They are out there sampling a marine environment in ways that we can't easily, so they are one of our best indicators of marine ecosystem health," Prof Phil Seddon, one of Young's supervisors, says.

One clear factor is ocean warming. Research by Dr Thomas Mattern, of the University of Otago, calculates that sea surface temperature explains about a third of the decline in adult hoiho numbers. In seasons with warmer than normal sea surface temperatures, fewer adults hoiho survive.

"You change the water temperature and this will flow through to a whole lot of other things."

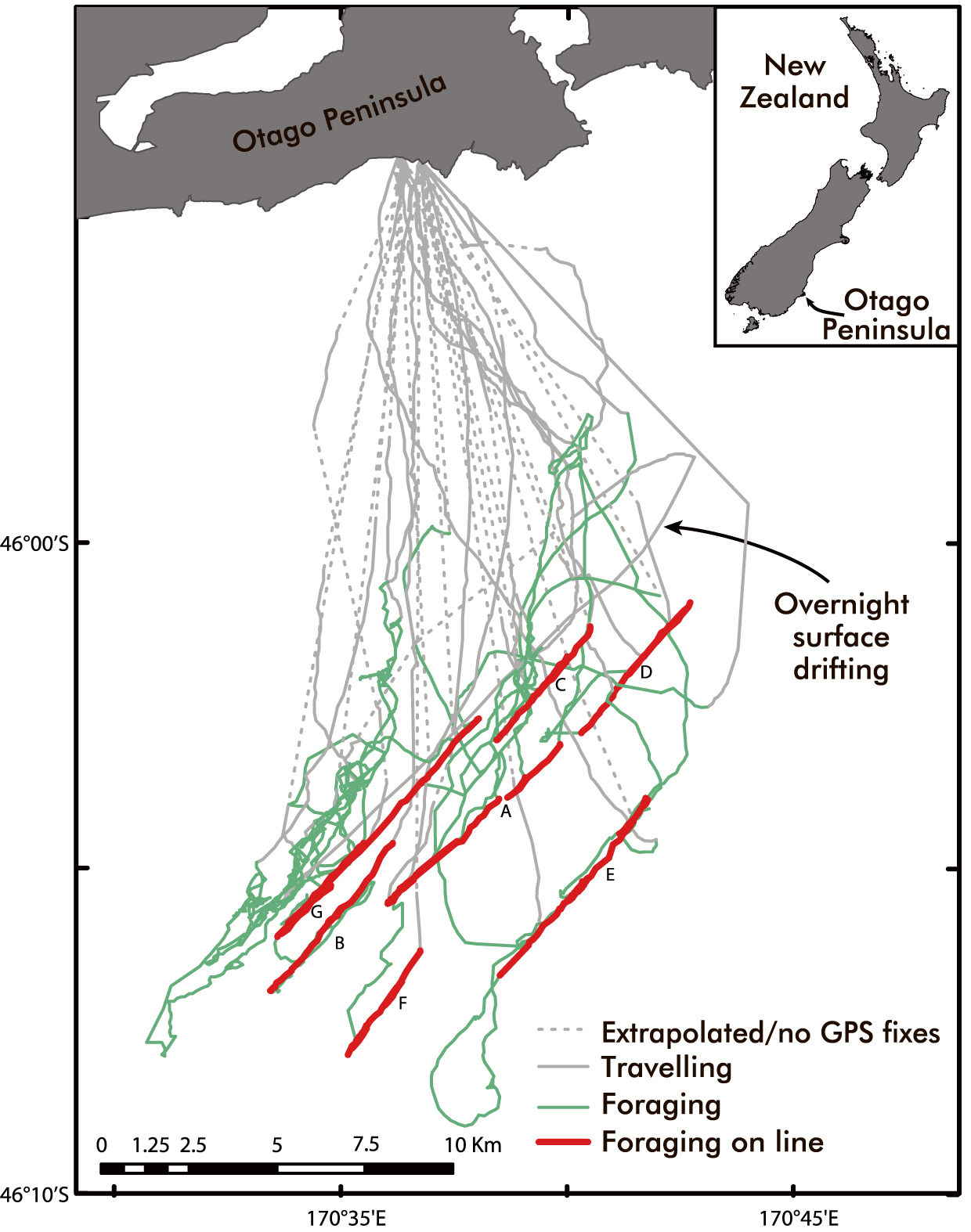

Bottom-trawling may also have altered hoiho feeding habits. Using GPS technology, Mattern has discovered that some birds are travelling in straight lines for many kilometres following the furrows in the ocean floor carved by bottom trawlers. The damaged ocean floor could be providing food for scavengers such as blue cod, which in turn attracts the hoiho, he says.

Mattern has seen the effects of bottom-trawling first hand.

"The things that get exposed are not in a very good shape. Banged-up horse mussels that are dead or dying, exposed worm holes. It's a pretty destructive fishery, bottom-trawling."

Added to this, commercial over-harvesting ripples outward to deplete the non-target fish community. For example, small fish enjoyed by hoiho, such as sprat, immature red cod, pilchard and ahuru were all once abundant in Otago Harbour, according to Dr Trudi Webster, conservation science adviser to YEPT.

Ocean floors heal and fish populations may recover, but this takes time. Analysing bottom-trawl data around the world, a 2017 study in Nature modelled that where 50% of the ocean floor's biomass is lost to trawling, the ocean floor will take between 1.9 and 6.4 years to recover. According to recent predictions by Mattern, hoiho on the mainland could be functionally extinct, that is, unable to recover, in as little as 10 years.

"Although the environment is changing in a way that's worse for the penguins, it's not an excuse not to manage the things we can manage," Seddon says.

One beacon for hoiho is that they have been observed to display "extraordinary plasticity," he says.

For example, when turbidity in the ocean has prevented them from seeing prey on the ocean floor, they have been observed eating larval fish harbouring among jellyfish in the mid ocean.

"So that's hopeful."

The presence of the southern population also brings promise.

"I think everyone is hoping that the populations down there are healthy and robust and that we are still going to have yellow-eyed penguins in the world if, worst-case scenario, we lose them on the mainland," Seddon says.

To help mitigate climate change, the Government expects to implement the Zero Carbon Bill later this year, but more action will be needed than this to turn the tide of decline for hoiho. It's the reason, according to Conservation Minister Eugenie Sage, that every bird in the mainland, Rakiura and Whenua Hou population is absolutely critical.

"It's why so much is invested in terms of rehabilitation of sick and injured birds, because these bigger impacts like changing sea temperatures, and potential effects on fish species they depend on - they can't be solved easily."

Hoiho face diverse challenges, including at-sea threats such as aquatic pollution and set netting, terrestrial threats including introduced predators and wildfire, and avian diphtheria and avian malaria disease outbreaks.

And these threats change every season, points out Bruce McKinlay, technical adviser ecology at Doc.

"A lot of our rangers have been really stressed out over the years because they think they are planning for one thing, and it's not, it's something different."

But hoiho have many helpers working independently and collaboratively, who once a year meet face to face at the Yellow-eyed Penguin annual symposium, run for 33 years, to share knowledge, findings and ideas.

All eyes are now on the strategic partnership recently established by the Department of Conservation that includes the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust, Ngai Tahu and Fisheries New Zealand. Last month the governance group released its 10-year draft strategy Te Kaweka Takohaka mo te Hoiho.

The strategy's purpose is to provide an over-arching framework and plan of action to halt the decline of hoiho on the Mainland, including Rakiura and Whenua Hou, and to return hoiho over the next 20 years to a "self-sustaining thriving species". A technical group will carry out the work according to a rolling five-year action plan for which public submissions close on September 20.

Ngai Tahu representative Yvette Couch-Lewis is co-chair of the strategic governance group.

"It's not so much about co-ordination, it's about enabling things to happen - that you put key people at the decision-making table to make it happen."

This includes the fishing industry.

In a statement, Alan Frazer, Fisheries New Zealand team manager inshore fisheries south, said: "As agencies, we owe it to these volunteers to do our utmost to ensure that the work on hoiho is co-ordinated, based on the best available scientific information, and that it is focused on the areas that will make the most difference to hoiho in the long-run."

McKinlay, in his role as leader of the hoiho technical group, values how different the process is compared with past initiatives.

"It is pretty neat to be there, and to be part of it because you are getting all of these perspectives at the get-go, not as a result of consultation and people feeling aggrieved after the fact. So that's all good!"

Looking forward, Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust general manager Sue Murray hopes this new approach will pave the way for recovery work.

The action plan brings researcher Young new hope for the species.

"Wherever I end up in five, 10, 20 years, I hope that I am still involved and we've seen a turn around."

The recent decline of hoiho has hit the community hard she says, but it is the people who make the effort worthwhile.

"Being out and about as we all are, often you spend a lot of time alone, but you are not alone because it's an awesome community."

Young is referring to people such as 2019 MNZM recipient, Rosalie Goldsworthy, from Penguin Rescue, who rings her and others weekly.

"She's just a lovely human being and she wants to make sure that we're all OK as people and that's particularly important over the last number of years when things have been really tough - to have that human connection. You know that you have people around you who understand how things are."

Dr Erpur Hansen, director of the South Iceland Nature Research Centre with Toti the puffin. Photo: Supplied

Puffins' plight parallels

Dr Erpur Hansen, director of the South Iceland Nature Research Centre with Toti the puffin. Photo: Supplied

Puffins' plight parallels

Something like 2.7million Atlantic puffin burrows pin-cushion the islands and coastline of Iceland, where 36-40% of the world's Atlantic puffin breed. It's a big number that's getting smaller, with a "decline of around 2 to 4% of birds every year since 2003", according to Dr Erpur Snaer Hansen, director of the South Iceland Nature Research Centre.

Like yellow-eyed penguin researcher Mel Young, Hansen has started collecting data from passive faecal samples using DNA barcoding.

"If it works it will give us the foodweb - not only their diet and what they are eating but ... the whole network of predators involved."

Typically, puffins eat small oily fish, capelin and sandeels, depending on their range, Hansen says, and when they don't have enough food, they stop feeding their pufflings. What Hansen has found is a shift in the birds' diet as fish populations have moved or collapsed, and that poor puffling survival is correlated with a rise in sea surface temperatures.

Similar to the Pacific's El Nino-Southern Oscillation that's driven by a warm ocean current, the ocean around Iceland is influenced by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Currently in a warm period exacerbated globally by climate change, ocean changes are hitting the puffins hard, Hansen says. "Our cycles predict that we will have cooling around 2030, but the oceanographers don't know to what extent global warming will actually counteract it fully, so it might never really cool. If that happens we are on a one-way street to losing our birds here, [in the west and east of Iceland] and the only ones really remaining that are doing OK are in the north."

Hansen's hunch is that the phytoplankton blooming later over the past decade has affected the rest of the food chain, including the sandeels and the puffins.

"Phytoplankton are the basis for everything else."

Like hoiho, long-lived puffins can weather a few bad seasons - but not too many.

Emeritus Prof Mike Harris, of the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in the UK, and co-author of The Puffin, says time to adapt is a key factor.

"If extreme events occur too frequently, then they have trouble adapting and the population will decline."

Sue Maturin

Deadly bycatch

Sue Maturin

Deadly bycatch

Set nets don't discriminate between fish and the penguins that chase them. While recreational set-netting in Mainland hoiho territory is now prohibited within four nautical miles from shore except at harbour entrances, commercial set-netting continues where hoiho feed. According to Forest and Bird, yellow-eyed penguin deaths are usually only reported from boats with observers, and during the 2017-2018 season, the advocacy group estimate that up to 30 hoiho could have been caught as commercial bycatch across the birds' foraging areas.

The Ministry for Primary Industries has recorded an average of two reported captures per year from 2015 to 2018, inclusive, and estimate that about 17 birds could be killed as bycatch annually.

"A full scientific reassessment of fishing-related hoiho captures will be completed next year," according to an MPI spokesperson.

A National Plan of Action on Sea Birds is due to be released for public consultation within the next few months.

Meanwhile, pushing ahead with urgency, Forest and Bird are asking the public to sign a Zero Bycatch Pledge on their website.

"We don't eat yellow-eyed penguins so we shouldn't be catching them. Every penguin counts," says Forest and Bird Otago and Southland central regional manager Sue Maturin.