Good news and climate change. You don’t see that in the same sentence very often.

But here’s some: Dunedin’s total gross emissions declined 9% between 2018-19 and 2021-22.

That welcome achievement was announced a few weeks back in the Dunedin City Council’s latest Dunedin Community Carbon Footprint Update.

It’s arguable it didn’t get the standing ovation it deserved.

Sure, we are talking about the Covid years when planes loitered dejected in the hangar and cars spent even more time than usual parked up.

However, a quick dig into the comprehensive set of numbers and charts in the update indicates there’s some baked in cause for optimism — a switch away from coal, for example — change going on that’s delivering emissions reductions regardless of our pandemic setting.

It could be that this is what puts the spring in Jinty MacTavish’s step, the council’s principal policy adviser sustainability. She’s just breezed in from a meeting at the university, wearing her shoes made for walking. And that’s just what she’s done, covered the distance between the campus and our Civic Plaza meeting room in about 12 minutes — she gave herself 10 minutes to do it, so she’s apologising for running two minutes late. No problem though, and no carbon emissions.

She’s also had a meeting out in Green Island on the day we meet. That’s what we’re hear to talk about — why all these meetings?

MacTavish — one time councillor, now civil servant — is an important cog in the council’s effort to go net zero carbon by 2030. Not just the council, the entire city. And on this warm autumn Dunedin day, she’s been out talking to folks in Green Island about how we might get there.

She also wants to hear from you.

The council’s running an online survey this month, the Zero Carbon Otepoti survey, to inform a plan of action that will go to the council mid-year. The survey concentrates on transport, waste and energy and doesn’t take long.

Sample section: "My household would send less waste to landfill if ..."

If access to a woodchipper would help you do that, you can tick that box. Or if sharing stuff would make the difference for you, you can tick that box.

There are lots of boxes to choose from, on purpose.

We know we have a very diverse community, different needs and lifestyles, MacTavish says. So different actions will be more or less possible and what’s required to support those actions will be different.

"That’s what our current engagement is about, it’s about understanding people’s needs and aspirations for their own low-emissions lifestyles and what our city council role is in helping support that."

We have our own quirky collection of demographics and ways of doing things, specific to Otepoti. Fortunately, we do know quite a lot about them already, thanks to research going back years by the likes of Prof Janet Stephenson and her colleagues at the University of Otago’s sustainability centre.

But before we talk further about that, we might just double back to see how we arrived here.

Climate change, obviously, has been on the agenda for decades now, international efforts to confront the issue culminating in Paris in 2015 with an agreement to limit warming to well below 2degC, preferably 1.5degC.

By the following year, the DCC had published its first community carbon footprint, one of the country’s first cities to do so. Then, following the big School Strike 4 Climate marches in 2019, the council declared a climate emergency and adopted the 2030 net zero target.

There’s been a good bit of activity since.

At the council all work must now consider the impact on emissions, big pieces of work such as Waste Futures — with its aim of keeping methane producing food and green waste out of the landfill — are specifically targeting reductions.

More recently, just last year, the city established the Zero Carbon Alliance together with the University of Otago, Te Pukenga, Te Whatu Ora and the Otago Regional Council. Te Whatu Ora and the polytechnic, as part of the Carbon Neutral Government Programme, are working to hit net zero for their operations by 2025, while the university has set itself a target to reduce gross emissions by 56% by 2029, consistent with a pathway of limiting warming to 1.5degC.

The private sector’s engaged too, Business South is measuring and reporting emissions, Silver Fern Farms intends to cut gross emissions by 42% by 2030 and Anderson Lloyd plans to be net positive by 2030.

Dunedin’s getting busy then and those charged with co-ordinating the effort are swatting up on best practice. But as MacTavish has already outlined, one size does not fit all.

For example, travel surveys carried out by the Zero Carbon Alliance partners identified a range of behaviours.

"When we look at the travel survey data for each of those institutions, the staff travel survey data, it is very different the ways people are getting to work," MacTavish says.

"The solutions for each of our neighbourhoods are going to look quite different."

The survey will help find them, as will the rounds of meetings MacTavish is engaged in, like the one in Green Island.

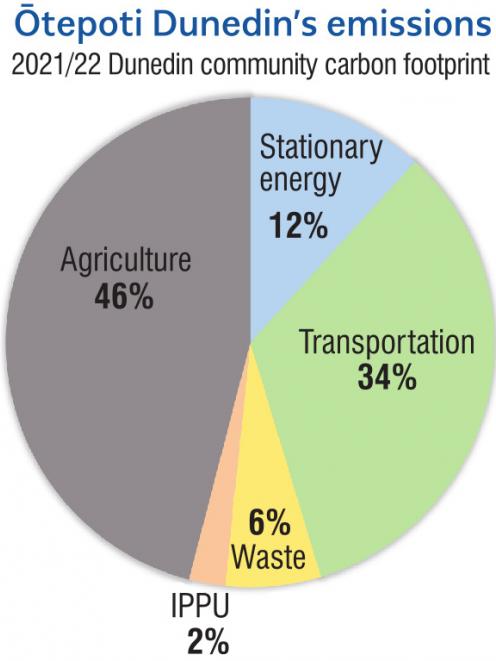

Transport is a big part of the zero carbon work. Cars contribute 48.1% of the city’s transport emissions. Transport is 34% of total city emissions, second only to agricultural emissions.

And if we’re thinking about Green Island, MacTavish says identifying a low-emission transport solution for a family of four living there needs to examine the practicalities.

For example, cycling infrastructure might not be there to support biking, she says.

"And if it is the bus, what are the current barriers or the challenges with that service that means it is not attractive to you or not possible for you. That way we can target the interventions for those people who are most likely to use those services in the places where those services are most likely to be used."

If we can do that, Prof Stephenson says, we can normalise that sort of low-carbon behaviour for the family’s children, the next generation.

Despite MacTavish’s impenetrable air of can-do, this all still presents as a pretty big job. Zero carbon by 2030, possible much? MacTavish reiterates that we’re not the first to do this, while clarifying that yes, she’s aware of the size of the mountain.

Auckland is also a long way down this road, she notes, having last year published a new emissions reduction plan for transport there: "Sustainable Access for a Thriving Future".

"The pathway requires every lever available to be pulled as hard as is credibly possible," the plan says. "Mode shift, electric vehicle uptake, reduction in car trips and every other lever are all stretched to the limit of what is possible in eight years to chart a path to a 64% reduction in transport emissions."

MacTavish confirms, "It is possible but we do need to make changes and we need to make them quite quickly.

"It will be a combination of all of those things and actions that everyone takes — businesses, organisations, institutions, councils, service providers — that will get us there."

Prof Stephenson says the city is fortunate to still have good bones, community hubs that can be refreshed to become the centres for walkable 15-minute neighbourhoods. And says the sorts of changes being mooted will not only reduce emissions but also build resilience to the impacts of climate change.

A further part of the picture is what central government is up to. Among it, last year’s first national emissions reduction plan, "Te hau mārohi ki anamata: Towards a productive, sustainable and inclusive economy".

On transport, it flagged that there would soon be reduction targets for vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT) in our main urban areas and programmes to get there.

Dunedin can expect to be handed its programme next year.

And, actually, is in reasonable shape to take it on, as Otepoti has the second-lowest VKT per capita of New Zealand cities, and the second-highest rate of EV ownership. We are already about double the national average for walking to work or education.

People in inner-city townhouses are more likely to walk, cycle or bus to work, one thing building on another.

That sort of dynamic tends to snowball, piling on the co-benefits so often touted for emission reduction initiatives.

With transport, as people get active, the air gets cleaner, the streets get safer for school children. MacTavish’s list goes on.

Or take waste.

"If we are wasting less as a city, we are saving money, we are polluting our environment less," she says.

Materials previously discarded find new uses and new enterprises emerge to take advantage.

So, all of this thinking — pulling in advice from academics, practitioners and the public, building on the experience of others — will be rolled into that plan to go before council mid-year.

"For example, it will say ‘in order to achieve council’s emissions reduction target, we are likely to need ‘x’ reduction in transport emissions, and this would be made up by ‘x’ percent increase in walking and cycling, ‘x’ percent increase in public transport use, etc, etc. And in order to achieve those shifts in mode choice the evidence base and the engagement we’ve had from our community suggests that x, y and z actions are the next steps that we need to take’."

There’s still time to feed into that process.

Jinty MacTavish is keen to hear from you.

Having your say

The Dunedin City Council (DCC) is gathering the views of the city on reaching the goal of zero carbon by 2030. Those views will inform a plan of action due to go before council by the middle of the year.

The online survey

The short Zero Carbon Otepoti online survey is gathering views on transport, waste and energy until the end of the month.

For transport, the council’s zero carbon plan will aim to make it easier for people to travel in low-carbon ways. So, that’s actively — walking or on a bike, for example — or on public transport.

The survey asks about the barriers people think there are now to doing that, and what they think would help.

For waste, the council is reducing what goes to landfill, to cut methane emissions in particular. The survey asks what might achieve that.

For energy, the council’s zero carbon plan will promote cleaner sources of energy, alongside energy efficiency. The survey aims to get a snapshot of what people are doing now in these areas.

The vision

The council is also inviting the city’s young people to put forward their visions for what a zero carbon Ōtepoti might look like.

Those visions will help shape the council’s plan to get there by 2030.

Young people can express their vision for the city in any way they like — as a drawing or poster, by writing a letter or an essay, by creating a sculpture or by writing or performing a song or a dance.

Selected works will be exhibited to celebrate the community’s vision.

The last date to submit your work to the DCC is March 31, 2023.

- More details are on the DCC website at www.dunedin.govt.nz/dunedin-city/climate-change/your-vision-for-a-zero-c....