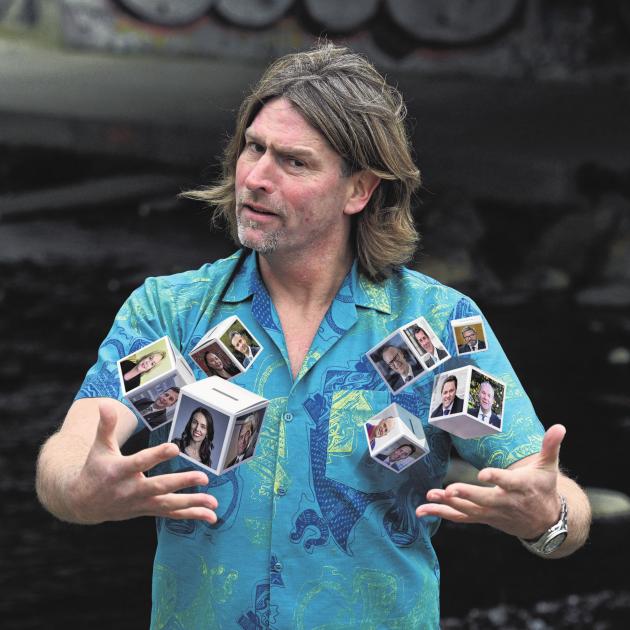

"All of those people, as far as I can see, had objectives that weren’t necessarily related to what they were caught for," Prof Paul Hansen says, scanning a list of New Zealand politicians who, in a rash of scandals, have recently lost positions of power.

"Most people aren’t just trying to achieve one thing in their life. There are trade-offs," the University of Otago economist and co-founder of global decision-making company 1000Minds explains.

"In the pursuit of one objective, like finding a new girlfriend; that might cause you to do stupid things that end your political career.

"Or like loving your children and your wife and wanting to have a nice recreational time with them at the beach ... But it violates some other objective that might be important in your life too, like ... setting an example."

New Zealand is having a bad run with politicians’ decisions.

During July, two members of Parliament lost political careers and three lost parliamentary roles for their parts in scandals ranging from an extramarital affair and allegedly sending young women porn to beach trips during the Level 4 lockdown and mishandling Covid-19 patients’ private details.

It has been particularly pronounced in the South where, during the past four years, five politicians have resigned or been reassigned for misdemeanours involving secret recordings, secret meetings, secret visits and not-secret-enough details.

Are the current crop of politicians particularly prone to making dumb decisions? Is something broken in the way we select political candidates? Or is it bigger than that? With a general election next month, plus referendums on legalising euthanasia and recreational cannabis, do we all need to learn to make smarter choices?

The politicians who "fell from grace" made mistakes somewhere in the decision-making process, Prof Hansen argues.

"They didn’t sit down and work out the trade-offs properly, or they didn’t have enough information about them, or they acted on impulse."

If they had given it enough thought and time, they might well have chosen differently

"They probably certainly would have with hindsight. So what stopped them?"

Being human, it appears.

"This is especially true when people are under pressure or are otherwise not motivated to reach the best decisions, which is a lot of the time," Prof Halberstadt says.

A common mistake is basing decisions on whatever facts come to mind in the moment. The result can be a disastrous miscalculation of the risk inherent in a decision — as we have seen so frequently in recent weeks.

Another barrier to sensible choices, Prof Halberstadt says, is the trouble people have knowing how they will feel when in a different state of mind. In a "hot state", it can be difficult to figure out what your "cold state" self would feel about the plan you are about to execute. Competing priorities do not get a fair hearing and the person is left to rue the result.

Politicians could benefit, Prof Hansen suggests, from taking Benjamin Franklin’s advice. The American Founding Father famously outlined his decision-making process in a 1772 letter, advising London chemist Joseph Priestley to begin problem solving by creating lists of "pros" and "cons", for and against, for the choice he faced.

"That would work really well for those binary yes-no decisions," Prof Hansen says.

"Should I send nude pictures to young women? What are the pros? What are the cons?"

Another fraught decision-making option is "going with your gut".

Some say the subconscious is a sophisticated and rational information processor that is best left to do its job without the interference of facts or deliberate thought.

Canadian author Malcolm Gladwell, for example, wrote the bestseller Blink. Its message, Prof Hansen says, is "Don’t think — you’ll just know".

Support for intuition-based decisions has also come from the likes of German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer, who showed cases where ignorance produced better decision-making, Prof Halberstadt says.

Some argue that what some people call "gut instinct" is actually knowledge born of experience. Others say important decisions should always be well thought out or they will lead to mistakes.

"But we all like to think we’re smarter than the average bear," Prof Hansen adds.

Could it be that gut instinct and first impressions are playing a negative role in the selection of electoral candidates by political parties? Just because the candidate committee’s chairman likes the cut of the contender’s jib doesn’t mean they are necessarily cut out for the job of elected representative.

Trying to reach consensus about which candidate the committee should select can also be difficult. There the problem can be conflicting but unspoken values held by committee members.

"Our values, how we trade off the pros against the cons; that’s the fundamental thing," Prof Hansen says.

"Most of us have different values. It’s just the nature of being an individual. So getting those values out front and centre and being able to see other people’s points of view; that’s the crux of the problem. That’s when we can have a proper communication.

"We might not agree. But at least I can see your point of view."

The University of Auckland electoral system researcher says there are differences in selection methods, ranging from the comparatively decentralised Greens, through Labour and National with a mix of regional and head-office involvement, to The Opportunity Party at the more centralised end of the spectrum.

She says candidates are thoroughly vetted by parties, but it is inevitable some unworthy ones will slip through or that some decent ones will do something stupid.

Despite recent controversies, there is no reason to think poor candidate selection is an issue, she says.

Group decision-making dynamics are not a factor when a citizen is standing alone in a voting booth, pen in hand. There, other challenges need to be overcome when trying to make smart choices.

That process, Prof Halberstadt says, needs to begin long before we find ourselves staring blankly at a dizzying array of unknown names on a voting form.

He does worry about the wholesale ignorance of some sections of the voting population. The quality of information used in decision-making is critical, Prof Halberstadt says.

Davis, who teaches the University of Otago Summer School course on fake news, misinformation and disinformation, thinks the proliferation of untruth is a "virus" that has the potential to do more damage than the coronavirus pandemic.

"If we lose the ability to agree on a set of facts on which we can debate anything, we are doomed.

"Facebook, as far as I’m concerned, is the evil empire now ... The algorithm amplifies disinformation and misinformation."

Davis says politicians in many countries, including New Zealand, are using social media to distort debates.

A fortnight ago, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters confirmed the party had contracted election campaign services from wealthy United Kingdom businessman Arron Banks and political activist Andy Wigmore — aka the "Bad Boys of Brexit" — who were behind the Leave.EU campaign. That campaign weaponised negative emotions such as anger and irritation — which spread more quickly on social media than positive messaging — to galvanise and build support.

Last month, Wigmore was reported as saying he would be causing "mischief, mayhem and guerrilla warfare in the New Zealand election".

Davis teaches his students to be savvy media consumers who find multiple corroborating sources before sharing information online.

Determining which information sources to trust is crucial. A good guide is whether they correct their mistakes, he says.

"If the ODT makes a mistake, it corrects it. If the BBC or The New York Times get something wrong, they correct it.

"If the news organisation is honest enough to correct its mistakes, then it is probably honest enough to report the news properly."

If taking time to gather good information is fundamental when facing big decisions, clarifying values is key to actually making good choices.

Next month’s referendums make that clear. Do you support the proposed Cannabis Legalisation and Control Bill? Do you support the End of Life Choice Act 2019 coming into force? Simple questions that beg so many others. And thoughtful decisions are impossible without sorting, for example, what value you place on potential harm to a minority of cannabis users compared with the potential benefits of eliminating illegal supply. Or, in the case of assisted dying, what value you place on sanctity of life compared with quality of life.

Hansen harks back to Franklin’s letter, saying his big contribution to decision-making was the advice to give a value rating to each item on the lists of pros and cons.

"All he’s saying is get a sheet of paper, divide it into pros and cons, spend the day filling it in."

Then assign weights to each item based on its importance or value to you. Finally, cross out evenly weighted items in both columns until only one column has items not crossed out.

"The reason I find it attractive is that anyone can do it with a sheet of paper," Prof Hansen says.

"You could do that with the cannabis and euthanasia questions."

It is important to remember, Prof Halberstadt says, that people do not all share the same values.

The decision-making process and the outcome are two separate elements. It is quite possible for two people to each follow the same, good process yet, because of their different values, come to completely different decisions.

We need to be respectful of those differences, even when we disagree.

Other times, the process is faulty, the values are dubious and the outcome is a silly or stupid choice. Even then, some grace is required, both professors say.

"People are flawed and limited information processors. I’m generous when it comes to judging people’s behaviour," Prof Halberstadt says.

"I’m a fairly forgiving person," Prof Hansen adds.

"As I get older, I see my own mistakes all around me ... so a good point to end on is humility."

Not that that means no improvement is possible or no change is required.

Prof Halberstadt wonders whether people should have to demonstrate a minimum level of political knowledge before they are allowed to vote.

Political researcher Max Rashbrooke believes New Zealand definitely needs to move from a representative to a more democratic system.

"I think the best possible change we could make in our political system would be to give ordinary people the chance to discuss issues with each other, and then give the results of those discussions real weight in decision-making," Rashbrooke says.

The Victoria University of Wellington researcher says there is lots of evidence that, when it comes to big political problems, large groups of citizens can make better decisions than small groups of experts — and better than politicians alone . That, he says, is because one of the best guarantees of good decision-making is having a wide range of approaches, backgrounds and ways of thinking.

"But it’ll only be smart, obviously, if those ideas that are spread among us can be shared and brought to the surface. And that’ll only happen if people can intelligently discuss the issues."

Rashbrooke advocates citizens’ assemblies — where a representative group is brought together to debate an issue — whose recommendations directly determine or at least have a major bearing on the final decision.

"We need to harness the genuine wisdom of the crowd."