For well over 200 years, natural historians have been puzzled as to why insects (phylum arthropoda, subphylum hexapoda), arguably the most successful terrestrial animals, are so rare in marine ecosystems. This is in direct contrast to crustaceans (phylum arthropoda, subphylum crustacea) which for hundreds of millions of years have mastered the oceans. The crustacean class merostomata, which includes horseshoe crabs and the extinct eurypterids (crustaceans that grew to 3m long and roamed the seas from the Ordovician Period [505 million years ago] until the end of the Paleozoic Era [252 million years ago]), were dominant for exceptionally long periods of geological time. Horseshoe crabs appeared in the lower Paleozoic Era and have survived until the present day. But, despite their long endurance as sea creatures, crustaceans have enjoyed comparatively little success on land.

Last month, scientists from Tokyo Metropolitan University (TMU) proposed a convincing solution to this puzzle and seem to have found why insects have not reinvaded the sea. The university team earlier showed that insects evolved a unique chemical method to strengthen their exoskeletons by using molecular oxygen and the enzyme multicopper oxidase-2 (MCO2). They found this gives insects a strong disadvantage in seawater, while providing huge benefits on land. MCO2 is pivotal in the evolution of insects (particularly winged insects).

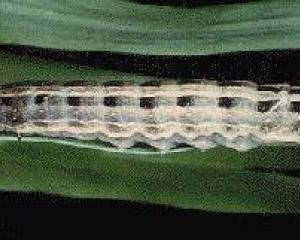

Associate Professor Tsunaki Asano and his Tokyo Metropolitan University team have put forward an elegant solution based on evolutionary genetics. They state that the latest research in molecular phylogenetics has revealed that crustaceans and insects belong to the same family, pancrustacea; insects comprising a branch that left the sea and adapted to land. Both crustacea and insects have an exoskeleton with a hard cuticle and a waxy epicuticular layer. The research showed that when insects became terrestrial, they evolved a special gene that makes MCO2 which hardens the cuticle using oxygen. MCO2 enables a reaction in the cuticle where molecular oxygen oxidises catecholamines, which bind and harden the surface. This differs from the process used by crustaceans, which harden their cuticles by using calcium from seawater. Professor Tsunaki Asano’s team reasons that this makes land much more suitable for insects because of the abundance there of oxygen. The sea has now become an inhospitable environment for insects due to the lack of oxygen, and also to the presence of already existing, better adapted, animals in the sea.

It is the nature of the lightweight insect cuticle that enabled their success, especially after flight evolved. The Japanese team believes that MCO2 is a defining feature of insects.

- By Anthony Harris