Because she had dementia this game wasn’t fun for the woman and I learned to sing in her ear instead of answering the same repetitive question. It didn’t matter where she was, because she could never get a fix on that and it haunted her. It mattered that we try to make things less miserable for her. She lived on chocolate biscuits and she was like a girl if she was caught with too many in her bed.

Gordy lived in the other wing and almost kicked me in the head once as I was putting on his slippers because, he’d rightly deduced, I was laughing at him not with him. I tried to get it right with him after that. I didn’t call him Gordy, the other caregiver did, I called him Gordon. Despite his grunts, I found him to be a formal person, he had his routines.

He devoured everything we put in front of him, I think he took three sugars in his tea. He would emerge with or without his walker at lunch, his pants falling down and his harmless growl, and would then fall flat on his face in the middle of the lounge and be helped back to his room. Wanting more food and more tea. I think we made him more than one cup at a time.

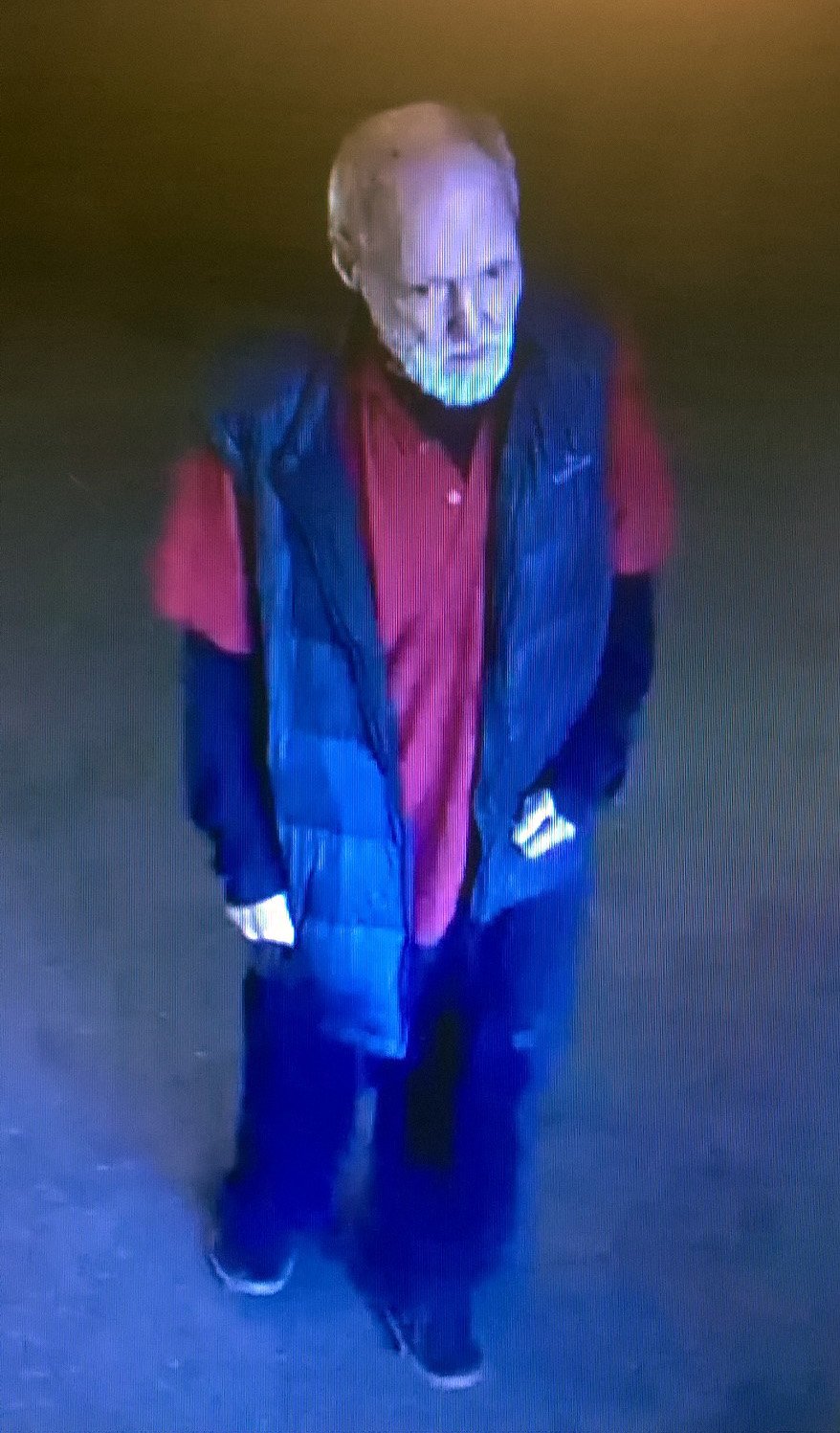

I was surprised to read he was not an eater when he went missing. I did not realise he had been moved up to the hospital from the unit either. In the CCTV footage of the last sighting of Gordon he looks gaunt, and smart in the Kathmandu puffer vest that would have been bought for him by a nurse or caregiver with money from the State.

Gordon had been in care on and off since he was young. And it wasn’t uncommon to get people with a schizophrenia diagnosis in our locked dementia unit. Everyone gets mushed together when you are old, but he would have been lucky to escape because you needed to remember a four-digit code to get out. I used to get a bit philosophical about that code when I punched it in, swinging in and out for my break like a breeze.

The woman Gordon shared a bathroom with was chair bound and highly medicated, she would sing, laugh and clutch a teddy or a doll. She reminded me of a Wild Thing from the children’s book by Maurice Sendak. In her room there was a ’60s photo of the two Maori boys she had adopted and sometimes she cried for one of them. She was big and strong and would kick at me too. But the main thing was she hated her shower, she would yell and cry the whole time, and Gordon would hear her. He knew she couldn’t move in the shower chair that doubles as a toilet.

It explained his refusal to shower. When I asked Gordon why he growled: "I hear you, I hear what you do to her". He did not want us to do the same thing to him so I would put a face cloth on his chair for a sponge down. He didn’t like to stand for long and had to be convinced to wear slippers.

Impatient to be alone he would lie sprawled horizontally on his low bed or tucked up like a cat in the sun after lunch.

A whole person. Never seen again. When Gordon went missing people looked for him. By chance there happened to be an elite search and rescue team doing an exercise nearby and they pitched in. Scanning the bush and the drains and down into the steeper parts of Kaikorai Valley. Pleas were made for people to check their sheds.

The thing is, I couldn’t imagine him getting far, which made it more of a mystery.

And he disappeared as a news story the way a missing child would not. A missing child causes a fever. There is an industrial complex of grief and longing built up around Madeleine McCann. Someone like Gordy needs to have people who care enough to sustain a relentless search. He didn’t have any friends and his sister was also in care. I read that he received a letter before he decided to walk off the grounds of Wakari, but there are people home in that suburb during the day. What portal did he shimmer through?

Wakari is easy to get lost in, I suppose, so many sheds, and bits of bush and ditches and gnarly cul de sacs. Still, it would be vulgar to suggest foul play, someone would have twitched their curtains at the sound of a car hitting someone. Surely? The mental health community are familiar neighbours in Wakari, walking down to the dairy past the rest home. Every suburb is a village if it still has a dairy at its heart.

And part of me felt happy when I first heard Gordon had escaped, because I knew a lot of that life to be torture even as I tried to administer care. The ringing sound of the woman’s terror in the shower and people patronising you as they heap sugar in your tea. The terrible smells in the stuffy air. Time and space looping and strung out as silly string.

It was the middle of spring when Gordon went missing and heading towards summer. The bulbs and the magnolias were fading off but blossoms were still prettying the modest brick houses of Wakari as he staggered past. I hope Gordy made it far enough to feel briefly free. I hope the air felt sweet and that he wasn’t too frightened.